Today, in DC, people are sporting red shirts and red scarves, red hats and pants, socks, one assumes underwear–and many of them are wandering toward the Supreme Court, where today there is hope that nine people dressed in black will carry forward a message of equality. There’s a buzz here, and it has encouraged me to think about diversity more broadly, to understand that tackling the issue of whiteness that has disseminated so widely through the blogosphere (and been discussed so eloquently just recently by Diane Ragsdale) is more difficult if we allow ourselves to only discuss the most obvious part of the problem.

Having a conversation about the diversity of the arts that centers so strongly and specifically around “whiteness” and, from there, on race and ethnicity as the benchmarks for diversity, as extraordinary and truly inspiring as that conversation has been, is, I fear, problematic for making true progress on diversification in the arts field. As much as I strongly believe in the racial diversification of the arts field (and, you know, everything), I have begun to fear that we’re inadvertently offering an out by focusing so specifically on one characteristic.

Discussing whiteness in a vacuum that seals it off from other types of diversity can allow people to feel like we’re ripping the cover off of something dark and hidden, something that makes them feel uncomfortable, to have a difficult and necessary conversation. People can wrestle with the demons of our generational past. They can speak to their internal selves, check their barometers, and assuage liberal guilt for the moments of casual racism they see by airing them. They can lament the reality, see the numbers, and express disbelief at our homogeneity. And then they can feel the full weight of 240-plus years of racial intractability and injustice, interwoven so seamlessly into our whole social fabric, and they can throw up their hands and say the problem is too big, the weight of the whiteness too great. And then they can continue on as they have, feeling better for having bared their souls, fought their demons, publicly voiced their accidental racism, and having changed very little.

This is my fear.

There is value in conversation. But there is more value in change.

The truth is, there’s an obvious and pervasive racial disparity both inside and outside the arts. But, whereas inside the arts we seem to be mostly having a conversation about it through a tiny microscope, diving deep into the perplexities of racial disparity as though it exists alone, in the larger world the conversation almost immediately rolls out large, expansive, complex. In focusing so specifically on race—on whiteness as a racial or ethnic construct—I worry that we are both laying a simplified screen over a terribly complex issue and setting up the field for a conversation about intractability instead of a conversation about manageable change.

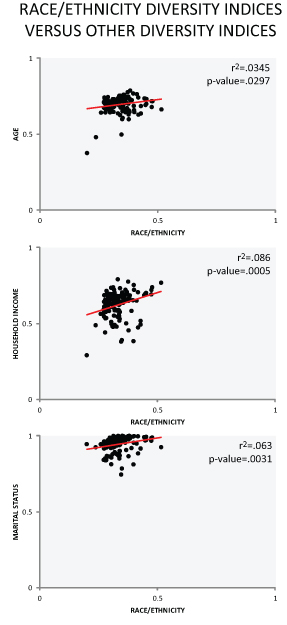

The diversity research I’m doing, the racial results of which I outlined previously, isn’t confined to race. We, in fact, looked at seven different types of diversity including race/ethnicity, age, gender, household income, political affiliation, marital status and educational attainment. And while there are a lot of findings around how those various types of diversity are affected by things like company size, average ticket price, and percentage spent on marketing, in the context of this conversation about whiteness, the finding that seems most germane is that race is correlated highly with some other types of diversity. In fact, at statistically significant rates, the racial/ethnic diversity of an audience increases in tandem with the household income diversity, the age diversity and the marital status diversity of that audience.

As baselines, audiences vs. general population statistics from the study were as follows:

- Race: Audiences 88% white, general population 42% white

- Household income: Audiences $108,000, general population $65,000

- Average age: Audiences 59 years, general population 48 years**

As a practical matter, this means that “more diversity” in these areas means (1) fewer white people, (2) more people who make less money, and (3) younger people.

To connect the dots, then, before even looking at the variations in company characteristics, we can identify things that may change (or at least change in tandem with) racial diversity—more racial diversity occurs in groups that are more economically diverse and more age diverse.

To connect the dots, then, before even looking at the variations in company characteristics, we can identify things that may change (or at least change in tandem with) racial diversity—more racial diversity occurs in groups that are more economically diverse and more age diverse.

Of course. Right?

We live in a country where being white, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, means on average that you have an average household income that is 158% that of a black family and 135% that of a Latino family. On top of the inherent disparity that immediately creates around ability to pay, household income, because of the strong pressures on monies allocated to the public school system in California, is strongly tied to the prevalence of arts education programs in schools—per the Irvine Foundation’s report An Unfinished Canvas, in all four genres (music, dance, drama and visual art), “students attending high poverty schools have less access to arts institutions than their peers in more affluent communities.” Because this economic segregation also generally incurs racial segregation (echoing the correlations we see in our theatre diversity study), those “high poverty schools” have higher rates of non-white children.

We live in a country where white populations are declining and Latino, mixed race and black populations are on the rise. Per the US Census Bureau, the average age of the white general population (all ages) is 37 years versus a black average age of 29 years and a Hispanic average age of 27 years. Audiences that manage to attract younger people will, by virtue of the higher rates of non-white within those age brackets, attain some level of further racial diversity.

These diversities are, themselves, connected with each other, of course, and with the other type of diversity that shows a significant correlation to race: marital status. Younger people are less likely to be married. Older people are, by virtue of being around longer, more likely to have paired off and become married. Married, older people are more likely to have more money. The stone rolls down the hill.

Does this all just make a complex problem more complex? I don’t think so. I think that it actually gives us more traction to actually get something done. We can stop (or at least stop only) asking ourselves “How do we get more people of color through the door?” and start asking more questions, none of which are necessarily easier but any of which might provide incremental change.

I once heard a managing director of a LORT level theatre say that she didn’t think we had a race issue in terms of theatre audiences, she thought we had a class issue. Her argument was that American racial disparity is primarily a class disparity, and—and here’s where I stop agreeing—that our best course of action as a field might be to simply wait a generation or two until more people of the other races have moved up the economic and class ladders, and, having now perched higher, will then have the resources and inclination to patronize the arts.

While my mind sort of disintegrates in the face of that argument (my mind immediately jumps to that quote from The Birdcage, “I assure you, Mother is just following a train of thought to a logical, yet absurd conclusion…much in the same way Jonathan Swift did when he suggested the Irish feed their babies to the rich.), I do believe we all must grapple with the inherent truth at the start of it—race is a class issue in America, and we have a complex and multi-faceted class problem on our hands. I grappled with what initially felt like a seeping of hope until I turned the conversation around for myself—knowing these interconnections is not a cause to freeze, overcome with the impossibility of the task, but is instead a grateful influx of more specifics, more details, which, when parsed, can lead us to experiments that may reveal how to get a little closer to point B from point A.

If we seek to diversify the arts—whether that’s because we think it’s right or because we’re worried about surviving or because we’re being forced to by funders or because of some other variation—we must do so with an understanding of the various parts of what that means. The weight we have been discussing in the blogosphere these last months is of “whiteness” only if whiteness is defined as something larger than skin color–a truth that, while difficult to swallow, is so much more holistically true and actionable than the narrower conception with which we’ve mostly been concerning ourselves. We cannot tune this violin by simply turning one peg—we must turn them all.

** (when you exclude anyone under 18, as we did for both samples in this research)

Portions of this blog post originally appeared, in slightly different form, in an article I wrote on racial diversity in Bay Area theatre for Theatre Bay Area magazine called “Who’s at the Table?” in 2010.

Clayton – thanks so much for your research and for your post. I would agree with everything you’ve written.

I think there is another aspect to this problem, though, and maybe you can help me put my finger on it. Let me throw out a short list of quotes:

“Ethnic [code for “black”] audiences don’t support the theater. They just don’t by tickets.”

“We like this play, but we’ve already got a black show on our season.”

“Ethnic [again code for “black”] writers are not good with deadlines.”

“I really like this show, but there’s one red flag for me: it’s black.”

What do these quotes have in common? They were all spoken directly to me by four different producers or people in positions of power at theater companies within the last 36 months. I’m talking about a Broadway producer (a producer known for giving opportunities to actors of color) and theater companies (and probably people) you know – the larger regionals and NYC-based non-profits.

In each case, these were words spoken by people who would self-identify as progressive and liberal. In each case, I shocked at what I was hearing.

In each of these cases, I was a writer and an outsider to the institution. But it felt like these sentiments were present at all of these organizations just below the surface.

What’s going on here?!? I don’t know what to make of this – especially at the non-profits, who should be the good guys in all this. Have we created a theater world so insular that people of color are seen by default as the “other” (even amongst people who hold very progressive political views)? Any thoughts?

There is so much one could say about your comment and about this particular issue (see http://t.co/RYgWXkkShI ), but your anecdote reminds me of one of my own — New friend: “I didn’t know you were Jewish; I mean… you don’t look Jewish.” [I was so taken aback I decided to call him on it.] Me: “I had my horns removed at birth.” New (former) friend: “Jews really have horns?” Me: “No, I was just trying to show you how ridiculous your comment was.”

My question is – did you call out any of those producers at that time? Sometimes we need to just say ; “Hey, wake up, you just made a total racist judgement about me – do you realize you did that?”

Change happens at the system level sometimes and the research Clay and his colleagues does can be used to suppor that, but change sometimes has to happen one person at a time.

Linda – I wish I had had the presence of mind to say something at the time in each of these cases. What I couldn’t figure out was how to say something without burning a bridge.

When the artistic director tells you that they can’t consider your work for this season because they

“already have a black play programmed,” how do you respond integrity in a position where you have very little power?

Let me put this out to any administrators out there: what’s the appropriate way for a writer (whose work is under consideration by your institution) to call you out on the racist assumptions of your worldview without (at best) coming across as sour grapes or (at worst) bringing his or her career to a grinding halt?

(should be “with integrity” – sorry – typing this on my phone from work)

Clay, I too agree with much of what you say here, about returning to an expanded conversation about diversity of all kinds. But I worry because I can hear in myself, and in you, and likely in your other readers, a readiness to give a sigh of relief–this confronting whiteness is just too hard, let’s talk about something else for a while. The demographer Dr. Manuel Pastor, known to GIA members for his keynote at the San Francisco conference, spoke last September to the Americans for the Arts National Arts Policy Roundtable, and he had a slightly different take on your proposal: as his parting shot, he said, sometimes the problems of racial and ethnic inequality are just to intractable to confront head-on situationally, in the moment (my words not his); if it is impossible to make any progress, open up the discussion. Specifically, discussion of generational change and the need to serve people of different generations will automatically take you to a discussion about different racial and ethnic groups (because of the generational imperative of demographic diversification we have all been talking about), but possibly through a less fraught lens. Clearly this is a demographer’s perspective but I liked that he offered an alternative way of talking about these issues without letting anybody off the hook of how difficult they are.