This is the first in a series of posts I’m planning to write about measuring and understanding goals around diversification of our boards, staffs, artists, art and audiences. I’m using this as an opportunity to work out thoughts, and I’m very much hoping you’ll help me — please give me your thoughts in the comments, as I’m writing this report and muddling through some very hard questions that need answers. Thanks – CL

I am deep into analyzing a giant dataset that combines data from our Arts & Culture Census, the California Cultural Data Project, the US Census, the California Secretary of State, Theatre Bay Area’s membership records and a lengthy survey distributed to 25 of our theatre companies, all of which is being combined in order to help us understand a lot more about how diversity works and has changed over the last 7 years. We were funded for the research by the California Arts Council, and I look forward to staring at the data more in order to see the patterns–but before we can really dive into any of that, there are, I think, two fundamental questions that this data bring up that we as a field don’t spend a whole lot of time on.

I am deep into analyzing a giant dataset that combines data from our Arts & Culture Census, the California Cultural Data Project, the US Census, the California Secretary of State, Theatre Bay Area’s membership records and a lengthy survey distributed to 25 of our theatre companies, all of which is being combined in order to help us understand a lot more about how diversity works and has changed over the last 7 years. We were funded for the research by the California Arts Council, and I look forward to staring at the data more in order to see the patterns–but before we can really dive into any of that, there are, I think, two fundamental questions that this data bring up that we as a field don’t spend a whole lot of time on.

If your theatre community is like ours, then you are likely feeling the pressure of diversity. We are, as a field, and really looking here at all the arts, woefully undiversified in terms of age, race and class. In the Bay Area, this is manifesting most strongly in the form of foundations either implicitly or explicitly letting fundees know that the diversification of their board, their staff, their audiences or all three may be required to secure further funding. Implicit in this is an assumption that diversification is good, and that one type of diversification (i.e. board) leads, ultimately, to other types (i.e. staff or audience).

Before doing a major study into diversification of theatre as a field, I think it is crucial to dive into the background on these two questions:

- What are the tangible data that indicate that diversification is necessary as well as good?

- What is the metric that we should be setting up for measuring success in such diversification efforts?

I am still reading up on the first one, but for now let’s assume (and I know it’s a big assumption) that yes, diversification is important for reasons of universal access, continued relevance and ongoing innovation and engagement both inside and outside the organization, etc. I’ll be writing more on that later.

So, for now, with that as a given: What is the metric that we should be setting up for measuring success in diversification efforts?

Diversification as it is currently being tossed about in the field seems a lot like the legend of Sisyphus to me. All rocks and hills, no end in sight, and therefore no option but to aim at the impossible or simply not try.

The mantra, which is often more of a directive, is simple and non-specific: “Become more diverse.” Where concrete numbers are given, they are most often centered around the top (board or staff) with admonitions that those bodies need to be X% diverse or have Y staff members. The directives come from boards or senior staff, but most often, and most persistently, they lately seem to be coming either formally or informally from program officers and granting guidelines. They are almost exclusively about race and ethnicity, almost never about age, gender or class. From what I have heard, the goals, if they exist, are arbitrary and not cued to anything particular about the organization. This is understandable, in a way, because it’s very hard to wrap your head around diversification in a way that is specific and actionable without seeming random. Unfortunately, that ends up being a very heavy rock to roll up an interminable hill–and sets up both a reality and an excuse that diversification is difficult and arbitrary, and each company too specific and unique, for the conversation to get very far and for companies that do make the effort to feel like they have gotten anywhere.

Part of the reticence we see in the field is because the problem seems daunting and abstract, without anything close to what we call at Theatre Bay Area “champagne popping moments.” Moreover, if companies are feeling reticent to wade into this particular issue, it is relatively easy to fall back on the idiosyncratic nature of the organization, the peculiarities of the artistic vision, etc. Perhaps that is why I am drawn to this project–I think, as with intrinsic impact, that we can actually put a metric on this problem, and that in doing so, we can make it more attainable and actionable.

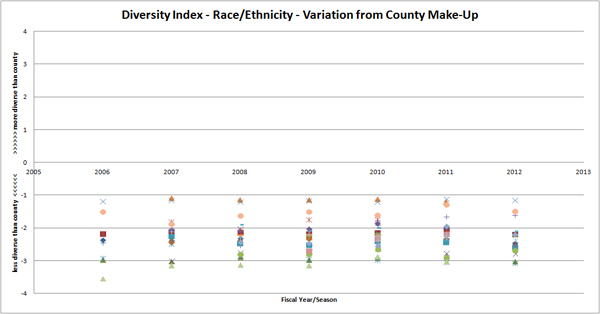

We are taking a stab at doing just that in this study, in part because otherwise we couldn’t figure out a meaningful way to compare organizations. The crux of the standardization is a formula that is used in both the life sciences and economics called the Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index. If you’re interested, here is the calculation:

Basically, what it does is it takes a set population that is partitioned in a certain way (for example, by race/ethnicity) and it calculates how far away from perfect parity (which is to say, even distribution across all categories) the population is. This allows us to see the basic standing of, for example, theatre company X versus the field when it comes to a particular type of diversity. What it doesn’t allow by itself is for us to understand what that means. Moreover, even if we do have a basic understanding of where we need to get in terms of diversity, a blanket approach allows organizations to assume that someone else is going to move on that–big companies say small companies are more nimble, small companies say that big companies can have a larger effect. So we have to peg it to something else.

In our case, what we are planning on doing is pegging that number to the similar diversity index of the general population using US Census information. We are looking at race/ethnicity, household income, gender, marital status, political affiliation and age. But what geographic (or other) range should we be talking about?

California is an incredibly diverse state–a majority-minority state, actually, and a crystal ball for what the rest of the country will look like in coming decades–but within the state there is substantial variation. Marin County, north of San Francisco and the preferred suburb of many of the wealthiest of the city, is strongly white and wealthy, whereas the counties of the East Bay (Contra Costa and Alameda) are substantially more diverse, younger, and less universally wealthy. So we have decided, for the sake of this research, to make the “target diversity” that of the county in which the company performs. This is imperfect, as from the Bay Area Cultural Asset Map (created by Ian Moss and others at Fractured Atlas) we know that while most attendance is fairly local, it generally does extend outside of the boundaries of the county (or, for small companies, can be hyper-focused to a particular town or city inside of that county), but short of some very complex calculations that we figure can be saved until this type of research is a little further along, we think that county-level diversity as the benchmark is a good compromise.

Of course, this doesn’t take into account lots of things: if a company is ethnically-specific, for example, they would likely not be a good candidate to index against the whole county. If a company primarily does classics, which were mostly written by men, it seems unrealistic that it could approach gender equity as would be required if the comparison were the county-level index. But it does throw out a yardstick, however imperfect it might be, in order to help companies gauge what their efforts might get them. In addition, and I think this is crucial, it allows companies to benchmark all types of diversity against something constant, and to therefore make decisions about which types of diversity to pursue and at what pace. It opens up a new type of conversation, which I think is essential to have, about priorities when it comes to diversity.

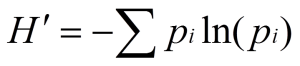

For example: what we are finding is that, generally speaking, the diversity index for gender for the audiences of almost all of the 25 organizations is within a very close margin of reflecting the actual gender make-up of the counties.

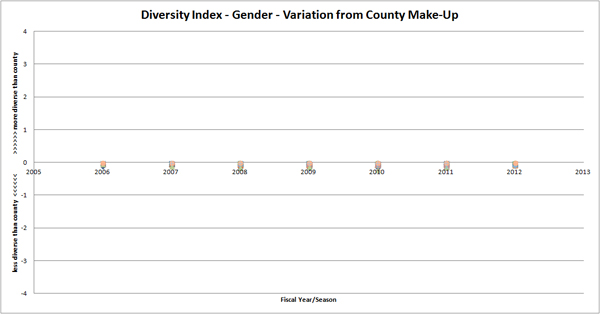

(To orient you to these graphs. These graphs show how much the company’s diversity index varies from that of its home county. As such, zero (the horizontal midline) is what we’re aiming for. Anything below zero (in the negatives) means that the company’s audience is less diverse than the county–and the farther from zero, the more less diverse. Anything above the midline (of which there are none in these graphs) indicates that the company’s audience is more diverse than the overall county–this is, for example, the case with education level because companies have more people with graduate degrees in their audiences than the overall population, which leads to something closer to equity).

The diversity index for race/ethnicity, on the other hand, is very far off.

Rather than having a conversation about blanket diversification, a company could instead discuss whether to pursue the incremental shift needed to bring the organization to true reflective gender parity with the county, or the larger efforts necessary to move toward race parity with the county.

What I’m Wondering

I’m wondering whether this makes sense. I’m wondering whether there is some other data-driven way of considering diversity and creating goal-based change. I question, somewhat, whether county-based parity makes as much sense when it comes to board and staff diversity–especially because this type of data-driven approach doesn’t take into particular account the larger societal disparities that exist around educational attainment, economic status and likelihood to attend/care about the institutional arts.

So I guess I’m looking for input–what should be the measure of diversity?

My question would be how you plan to assess whether or not your measure of diversity is valid/useful/makes sense. You note that you’re using the census results at the county level as the comparison group and you suggest that that could be optimized when “this type of research is a little further along,” but what are you optimizing for? How will you know whether diversity at the neighborhood level is a “better” benchmark for arts organizations of a certain type than using city, county, or state level data?

I also wonder how you expect this measure to be used. Do you imagine this tool will be used by arts organizations that want to measure their progress internally? Will it be used by funders to determine who is eligible for their grants? Is it to be used for academic research purposes? The answer to this might determine how accurate the calculation needs to be. If it’s “just” to be used for research purposes—I for one would be interested to know how the diversity of boards, staff, and audiences of theatres has developed in relation to the increasing diversity of the population over the years, just for the sake of knowing—it may not matter much whether you use city, state, or county data since you just need a reference value (which shouldn’t be entirely arbitrary, but might not need to be very precise either).

Related to the previous point, I wonder how your sample sizes will affect your results. I obviously don’t know the details of your study, but if you only have two staff members in a given organization, I assume it will be difficult to say anything statistically significant about the diversity of the staff. But if you’re talking about the diversity of all of the people employed by arts organizations in the Bay Area, one might reasonably expect to see the effects of the changing demographics of the population.

Good luck with this! I look forward to seeing the results!

Fascinating stuff, thank you for sharing it! Just a small anecdote: in the ’80s, I worked for a flagship arts company in London – 3 venues in one, the smallest of which was ‘a black box’, regarded almost as a ‘studio’ theatre, where a lot of new work was done, and where the design of the space deliberately allowed for different stage and seating layouts, where these movable seats were slightly less comfortable than in the other two auditoria, or sometimes were just removed altogether. Although we knew we had the stereotypical theatre audience in the other two venues, we all fondly believed (and believed we saw!) a very different, young, ‘studenty’ audience in the small space. After ten years’ operation, we brought in a research company who measured the audiences in the three auditoria along the lines you mention: age, gender, race, education level, location, income levels, and times attending per year. I’m not sure that disability was included but it may have been.The findings showed that the audience overall was white, middle aged, more female, highly educated and affluent. This was no surprise. But we were astonished to find that there was less than 0.2% difference between the ‘main houses’ and the ‘studio theatre’! Furthermore, we discovered that, far from being a national resource, our audience predominantly were the same two hundred thousand people who came from the Home Counties (i.e. nearby) with some coming as many 12 times a year. It was a real wake up call!

In the graph, what do the little icons arranged vertically mean? Does each represent a different company?

In general, this seems to me like a fair way of at least starting to benchmark the conversation. Of course there are complexities that aren’t accounted for, but when the data is this stark, there’s plenty of margin for such fuzziness before it ultimately affects the conclusions. I’ll be interested to see not just how the diversity measures compare to each other, but how they break down e.g. from county to county (are arts organizations likely to have a harder time matching the diversity of their county if the county is more diverse?), by budget size, etc. Looking forward to reading more!

Hi Ian, thanks! Yes, in the graphs each symbol is a different company’s score. What is interesting to me is that they all trend together, regardless of size, mission, etc. We are seeing exactly what you guessed, which is that companies in less diverse counties are, logically, closer to reaching the diversity profile of that county–that, I think, would be a shortcoming of this work, although honestly at a certain point maybe that is just the added burden you take up if you place your company in a more diverse place. In that way, it doesn’t become a conversation about just getting everything more diverse, but instead about accurately reflecting the world around your organization.

I’m pleased to see any attempt to quantify diversity in the arts and in theater specifically. There is so little data of any kind out there. One point that I would make perhaps is that funders have been looking at diversity issues for a very long time. This is not a new issue that organizations are having to struggle with today. This is an issue that has been squarely on the table for at least 20 years and we need to be reaching some more sophisticated ways of quantifying diversity and developing best practices.

I agree that the data-driven approach doesn’t take into account some of the more important factors that seem obvious when considering diversity in the arts. I would strongly suggest having a conversation with applied anthropologists – the University of South Florida’s applied anthropology program in particular – about qualitative and quantitative measurement techniques specific to their discipline that might be useful here.