On his way out the door, Rocco Landesman lobbed one final, wonderful bomb out there in a conversation with his counterpart in France (who, by the way, receives $9 billion-with-a-B in annual funding whereas the NEA has about $150 million). He was speaking at the World Arts Forum, and spoke about a “fundamental, visceral distrust of the arts” by the American public. He called the NEA funding level “pathetic,” and who can disagree, and his blunt honesty about what he called the arts’ “cowboy mentality” and lack of consideration of the reality in which we live echoes strongly for me with other things I’ve been reading about our particular insular issues.

Last week, I hosted, for Theatre Bay Area, the always fascinating Margy Waller in a presentation of her Arts Ripple Effect work for many of our leading Bay Area artists, thinkers and funders. The topic, as it always is with the Arts Ripple Effect report, was the framing of the arts—how we talk about the work we do, how we convince others of the value of what we value—with a particular focus on how that framing can happen independent of frequent, or event occasional, attendance.

Framing is a fascinating topic to me. In one way, it seems like such an obvious idea—it’s a science (well, as much of a science as psychology, which is to say my kind of science) of figuring out the vocabulary around an issue that will create a long-term shift in the thinking of the general public on that issue. It’s “right to choose” versus “right to life.” It’s “death panels,” “Romnesia,” “47 percent.”

In the case of the arts, a lot of our framing issue is tied up strongly in the articulation of “need” versus “want,” or, as Waller put it, “necessity versus nicety.” As I’ve gone on about on this blog before, through no particularly conscious effort, over the past thirty to forty years, a shift has occurred in American society that has primarily manifested (at least for our purposes) as an apathy and/or outright resentment of the fine arts, a belief that they are functionally a luxury, not a necessity, and perhaps most problematically, a given understanding that the fine arts, with all of their boxed up, appointed time, old tradition, surrounded by old white people issues, aren’t “for” most people. We are, it seems, in framing hell.

At the same time as we were presenting Waller and her Arts Ripple report, I came upon this discussion early on in Diane Ragsdale’s report, In the Intersection, which covers a convening between commercial and non-profit theatre producers hosted by the Center for Theatre Commons in 2011. As background, Ragsdale quickly recaps two other such convenings – one in 1974, called the First American Congress of Theater (FACT), and one that happened in 2011, called ACT TWO (clever, right?). In her description of FACT, she, drawing from the report written about that convening, says:

“The aim of the organizers of the First American Congress of Theater (FACT) in 1974 was to bring the leaders of American theater together to address a number of problems that could ‘no longer be dealt with effectively by any one segment of the community,’ including declining attendance and the need to stimulate youth and minority audiences, an economic recession, rising operating and production costs, and unreliable financing.”

This sentence caught me off-guard because, well, I still find myself caught off-guard when something that I feel is so idiosyncratically now—angst about youth and minority audiences, for example—is reframed as something that has been on the plate for 35 years. There is nothing new under the sun, it seems, and not in the arts, either.

I started getting this impulse to be incredulous at this idea—this idea that the theatre field would really have been so concerned about these same issues 35 years ago.

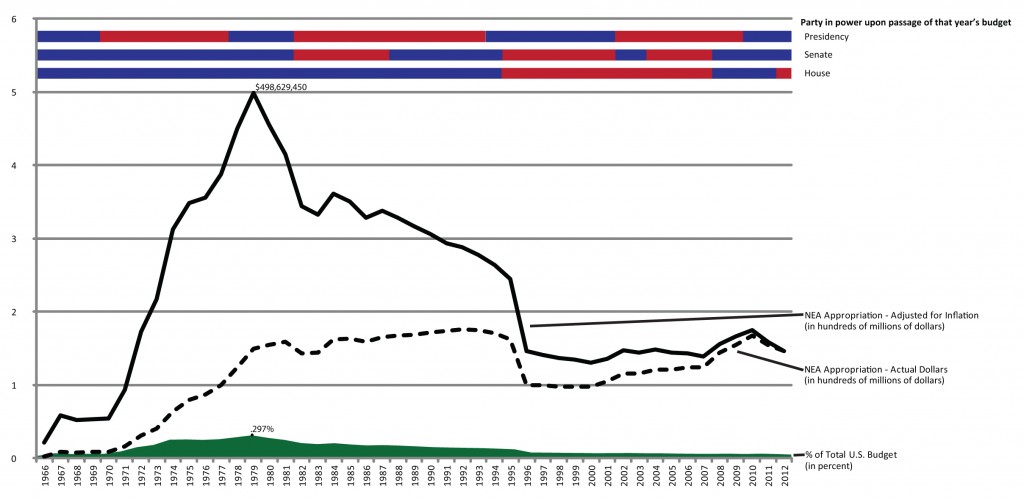

I found myself reflecting on the fact that in 1974, while of course we didn’t yet know it, the annual budget for the NEAwas marching upward toward what would be, in 1979, the largest NEA budget allocation ever when adjusted for inflation), when the agency budget made up .3% of the total US budget (compared to under .05% today—the smallest percentage of the US Budget in any year since the NEA was founded). The graph below, which I put together, looks at the NEA budget in actual dollars, inflated dollars, and as percentage of total budget–along with who was in power in each year (click to enlarge).

(Both of those percentages make me wince, and celebrating .3% as a high-water mark makes me sad.)

I found myself looking into US Census numbers and learning that, according to the 1970 US Census, there were an estimated 178,580,000 white people in the US, making up a whopping 87% of the population. By 2010, the percentage of whites in the country had gone down to 74%. In the Bay Area, from 1980 to 2010, the overall population rose by 2 million people, but we have experienced a net loss of over 500,000 white people, and a substantial rise instead in Hispanic and Asian citizens—and our overall Bay Area white, non-Hispanic population is currently 42%, putting us on the vanguard of that curious demographic issue known as the majority-minority society.

I found myself looking into US Census numbers and learning that, according to the 1970 US Census, there were an estimated 178,580,000 white people in the US, making up a whopping 87% of the population. By 2010, the percentage of whites in the country had gone down to 74%. In the Bay Area, from 1980 to 2010, the overall population rose by 2 million people, but we have experienced a net loss of over 500,000 white people, and a substantial rise instead in Hispanic and Asian citizens—and our overall Bay Area white, non-Hispanic population is currently 42%, putting us on the vanguard of that curious demographic issue known as the majority-minority society.

And, perhaps most importantly to this framing issue, I found myself noting that 1974 was two years after the Republican Party, in their convention party platform of 1972, professed, “For the future, we pledge continuance of our vigorous support of the arts and humanities,” and described the arts and humanities as a catalyst for “a richer life of the mind and the spirit.”

I’ve done some preliminary work looking at convention platforms and the NEA budget for a grant proposal we’re working on with Waller to better understand the effects of rhetoric on public perception and support of the arts over the past 50 years. It’s all early work, and incomplete, but from 1960 to 1972, the Republican platform did not mention art and the humanities at all, while the Democratic platform included soaring paragraphs about “encouraging and expanding participation in and appreciation of our cultural life” (1960). Over those twelve years, however, a clear linguistic shift occurred in the Democratic rhetoric: the seemingly innocuous insertion of the word “leisure” into the 1968 Democratic platform began a subtle but steady shift from portraying art as a necessity of civil society to art as a conduit to leisure. The term “productive leisure” cropped up in the 1968 Democratic platform, indicating a shift to a utilitarian or personal and individual view of art. When Republicans inserted a section on the arts and humanities into their platform in 1972, the rhetoric was, in many ways, more pro-arts than the corresponding section of the Democratic platform. The Republican platform described art and the humanities as a catalyst for “a richer life of the mind and the spirit,” and made reference to “our national culture.”

The 1972 Republican platform’s section on the arts and humanities closed with that sentence I quoted above: “For the future, we pledge continuance of our vigorous support of the arts and humanities.” By 1980, however, as Democratic platform rhetoric began to include verbiage like “the arts and humanities are a precious national resource,” Republican rhetoric shifted away from support of the NEA and public funding, and toward language that placed the burden for arts funding on the private sector and made government’s responsibility not direct funding, but tax incentives for private contributions. Over the ensuing sixteen years, Democratic platform rhetoric, while uniformly supportive of the place of arts in society, slowly transitioned to include more mention of the utilitarian aspects of art (education, literacy, etc) and to more consistently referencing private support alongside public. Republican support slowly eroded in that same period until, in 1996, the Republican platform expressly included a desire to defund the federal arts granting bodies, calling them “obsolete, redundant, [and] of limited value.”

(It is worth noting that, while that inclusion in 1996 is a huge landmark, the percolation around defunding the NEA started as early as 1980 with Ronald Reagan, who met enough resistance in Congress to the idea that he could only hobble the institution at the time.)

By 2000, Republicans had ceased talking about the arts and humanities at all, and “culture” was used only to reference concepts of morality and faith (13 times in the document). Over the past ten years, Democratic platforms mentioned arts and culture minimally and with vague expressions of support, while Republican platforms have discussed art not at all.

In short, between the rhetorical heyday of the 1970’s and today, we see the same problems in our perception, and are concerned about them in the same way. We claim to prize diversity, to be seeking out youth, to be worried about our financial model, our perception in society, our place. But the world has changed, and it’s hard for me to see how the world’s changing, in this context, has been anything but bad for our continued relevance in the conversation and support in the public space. With all of this information about the shifts that have happened since that first FACT meeting in the 1970’s, I can’t help but marvel at how much more urgent our angst is today, how difficult and necessary our task really is as a field, and how hard that task is going to be. Perhaps this is the hubris of being present in this moment, and as a colleague pointed out to me, everything looks rosier, or at least clearer, when all you have to reconstruct a moment is the orderly history that has been written down. All the same, this moment, now, as our Democratic president is about to move forward with limiting the tax-deductibility of charitable contributions and therefore lose our field tens of millions of dollars of support each year from private sources, I think I’m safe in saying we’re in trouble.

We suffer from a frame that couldn’t really be worse–inaccessible, elitist, luxurious, expensive, unnecessary, and unreflective. We live in a country that supports the (institutionalized—and I know there’s a big distinction there) arts less politically, rhetorically, and personally than at any other point in the past 50 years, that is muddling through a recession that is by most accounts worse than the recession in 1974, that has seen a precipitous decline in arts education and a precipitous rise in vitriol around art and it’s place in society. We live in a country where there are a million things to do, and within a population for many of whom attending a traditional arts event is low, low, low on the list.

It is always a problem when an era that seems rosy is revealed to have been fraught with the same anxieties as our own, and when in comparison our own era seems so much less hospitable to our continued existence than we thought (and honestly, we didn’t think much of its hospitability before).

In this environment, we must take a breath and understand the challenges we face, and we must work together to better understand how to face them. As individual artists, organizations, service organizations, arts agencies—whatever spot we take up in the arts bus—we need to stop discounting the changes around us, which I think we sometimes do when we don’t feel them in this moment, and to start getting smarter and more collaborative and more cooperative about how, when, and where we present our art and discuss our value. We need to, like any political movement, start figuring out how to speak with one voice, how to sing the same song—how to carry forward systematically and with shared purpose. We need to figure out ways of getting the great research that is being done, so dense and inaccessible when it’s sitting on the shelf, into the hands and minds of our soldiers, and need to learn how to turn everyone into a strong, strident arts advocate speaking from a place that is going to engender support, not throw up walls. We need to remind people that art is all around them, and that they are consuming it, reflecting back through it, living steeped in it like tea every day, and that the smell and the color and the texture of the work we make goes with them everywhere, and that that joyful humming of the world that comes from our art isn’t free, and is necessary, and is fragile and precious and in need of care.

This should come naturally to us, both because we all (one hopes) truly believe in the taste of this particular Kool-Aid and because we create messages designed to change the world every day. Let’s change the way the world sees us, too.

Thanks for your thoughtfulness. I wonder if our re-framing doesn’t also need to come with a significant re-framing of the arts experience as a whole.

Everybody on a Pittsburgh city bus on Monday morning has an opinion about the Steelers game the day before. They talk about QBs and half-backs and instant reply and have very strong opinions about the coaching decisions that were made–even though they’ve had no formal “sports education” in school. Why do they care so much?

Maybe because watching has become a cultural thing here. Maybe because every game they watch comes with 4 hours of talking heads educating them about the nuances of football rules. Maybe because the NFL marketing machine is ubiquitous. Or maybe because they are invited to have strong opinions, to shout at the screen and high-five, to drink at their seats and have fun…something that might actually resemble the first Globe Theatre?

The Heinz Endowments did a project back in 2008 that looked at the way audiences are expected to behave around art, and how that affected their experiences. Talking about a cultural shift around 1900, the project brief says, “As the audience moved into the darkness and the actors—or the dancers or the symphony musicians or the opera singers—moved into the light, the playhouse or concert hall moved from a site of active assembly ripe for public discussion and collective action to a site of quiet reception.”

I know that the arts are more than entertainment, like football. That sometimes difficult experiences are rewarding. But I also think we could do a lot to let go of the elitist “shoulds” around audience behavior that ostracize anyone who dares an emotional outburst beyond a thoughtful coo.

http://www.pittsburghartscouncil.org/storage/documents/Consulting/ArtExperienceIniative.pdf

I really appreciate this article and the comment above. I just wanted to add to the discussion of framing the arts experience from a college perspective. I help market the College of Visual and Performing Arts within the University of Toledo. So it goes without saying that I believe that the events we offer (concerts, plays, art exhibits and events) are truly unique and worth seeing. Funding is always a challenge but not necessarily the problem. It’s more a symptom. Funding follows when people value something.

I see our role in the arts as developing not only artists themselves but an audience that appreciates their work. One way we do this is by reaching out to high schools and middle schools and involve them in seeing and critiquing what they see, particularly in theatre. What concerns me though, is how hard it is to get people outside of the university environment and the schools , i.e. the general public to get the idea that coming to one of our plays, concerts or exhibits –even if no one they know will be involved–is worthwhile. I spoke to a woman once who fit that profile and asked her why she never attends any college-level arts offerings, even though she might attend similar events offered professionally. She said she never thought of these events as being something the public was invited to, that it was for the university community and the family and friends of those involved. Her comment blew me away! Essentially she was saying that her perception was that college is like high school and these events are for that community. How frustrating! But those kinds of perceptions dampen our ability to develop an audience beyond our university community to a larger community.

I could view that as just an unfortunate perception of college-level arts by an otherwise arts-friendly public except that professional arts organizations are having their own issues with attendance and funding. College-level arts are often the first place many young people are exposed to high quality visual and performing arts. For me, a major key to preserving community-wide love of the arts is to find ways to make that exposure transfer into a life-long appreciation of the arts, not something they set aside when they graduate, like cool books they read because they had to.

Why would either “old” (moneyed, white, elitist) or “new” audiences invest their time/money/attention to consume (and thus finance) art which fails to engage the issue in question: dissonance arising from increasing diversity? And this engagement needn’t be didactic, direct, agitprop-infused. We can be playful here!

@David Seals: great comment.

Clay,

it is perhaps worth noting two point with regard to the quote you excerpted from the report. (1) Broadway audiences had been declining in the previous three years and Broadway producers were sincerely worried they were in a dying industry; (2) they were the ones that initiated the meeting; (3) at the time the nonprofit theaters were getting subsidies and that did not appear to be going away; (4) some (hard to tell from the report how many) nonprofit representatives in attendance interpreted the invitation to partner to solve these challenges to be an attempt on the part of the commercial producers to benefit from tax subsidies by making the case that we are “all one theater” facing similar challenges; and (5) the nonprofit producers were disinclined to ally with the commercial producers.

I look forward to seeing your rhetorical analysis when it’s completed!

Just a very quick note to tell each of you how much I enjoyed reading your comments and the article.

I work for a performing arts organization and I completely relate with all of your views.

Keep the discussions going!

Yolande

First of all, thanks for the post. I look forward to reading your analysis of the changing political rhetoric about arts funding when it’s done.

I find it curious that in the midst of your critique of the way the arts are framed as a luxury rather than a necessity, you seem comfortable framing private donations to the arts as tax deductions. (I’m referring to the line about the president limiting the tax-deductibility of charitable contributions in your post, though the point is made much more forcibly in the Action Alert I received from Theatre Bay Area yesterday). Don’t get me wrong: I’m sure the tax deduction is an important driver of contributions to the arts. But I’m not convinced that’s the best way for us to be framing the discussion.

I don’t think we want to be perceived as defending tax breaks for the wealthy. That certainly won’t help us shed our reputation for being “inaccessible, elitist, luxurious, expensive, unnecessary, and unreflective.” We’re in a sticky situation in that our nonprofits and tax codes evolved in such a way that many arts organizations would most likely benefit from keeping as much wealth as possible in the hands of the wealthy. That’s not our fault; it’s the way our institutions evolved. But I wouldn’t go around advertising it.

In your post you ask us to “stop discounting the changes around us.” While eliminating tax-deductions would undoubtedly be devastating for many arts organizations, I can’t help thinking that something positive might come out of it, too. Might it be easier for us to adapt to the changing society around us if we weren’t dependent on gifts from our generous donors (wealthy, old, white) and the indirect government subsidies that come along with them?

In the last part of that question, I think I inadvertently hit upon the point that I’m actually trying to make here: In terms of framing, might it be better to specify that it’s the loss of the indirect government subsidies that we’re opposed to, not the loss of a tax break for the rich?

John, Unless we are on a political mission, can we really afford to and is it really desirable to choose audience. Instead of either/ or shouldn’t we rather focus on attracting any person with potential to love the arts and ask this person to support is with presence, financially and with ambassadorship.

One of the many challenges for the arts has been constant since the 1970’s: that audiences are very white and older. Similar to the Republican party’s recent experience, when there are fewer and fewer people who fit that demographic, traditional models for success can evaporate. The arts can continue to ignore trends in the population, or we can embrace those trends.

I’m not talking about putting an artist of color on a program and calling it outreach. This approach can be insulting to the very constituency that is being courted if it is not part of a larger effort to really engage that constituency. Many arts organizations are effectively engaging new constituencies by seeking out members of the constituencies for leadership positions, having a physical presence in communities of color, proposing solutions to problems using the arts and, in general, caring about the people in new markets as people, not just as sources of new revenue.

Diversity is here and the arts must respond with sincere efforts to make our tents larger.

A very nice piece. I keep vacillating on the question of how much times change and how much the discourse remains the same. Will the emerging generation support the arts? Will public policy respond to the needs of artists and arts organizations? It seems that we always have these questions and that some form of anxiety typifies every period, such that the discourse of anxiety seems unchanging even through changing times. That said, I share your opinion that this time is one of justifiable worry, moreso than at any time at least through the past fifty years, and so perhaps I too share your “hubris of being present in the moment.” All the numbers seem to be pointing in the wrong direction: decreasing NEA funding, institutional funder assets taking big hits in endowment values, decreasing audiences, increasing threats to philanthropy (cf. your comment on charitable giving deductibility).

I do not think that the sky is falling necessarily. Yet I do think action needs to be immediate, and I cannot think of a better place to start than with increasing collaboration and increasing innovation in the delivery of established art forms. Too often two problems seem to persist in arts organizations: first, that cooperation with other arts organizations somehow threatens their audience and their donor base — as if they will only lose and never gain — despite all research that indicates the contrary. Secondly, some organizations in the traditional art forms seem so resistant to changing format and delivery. The old problem of “We’ve never done it that way before.” Yet if we do not change, then we will continue to get the same results…and the same perils.