Before getting to the actual entry, a couple places I encourage you to visit.

(1) I was humbled to learn earlier this week that I was selected as one of the 50 Most Powerful and Influential People in the Non-Profit Arts in Barry Hessenius’ annual rundown. I’m honored, and thank everyone who reads this blog for the kind attention.

(2) A few months ago now, I was equally humbled to learn that a paper of mine, “Shattering the myth of the passive spectator: Entrepreneurial efforts to enhance participation in ‘non-participatory’ art,” was selected for publication in the inaugural issue of the online journal Artivate. The paper, and the whole first issue, will be published on September 1, and I hope you will both read my piece, which is a deep dive into the perilous term “participation” in context with presentational art, and the other selected in the journal. Click here for all the abstracts from Volume 1, Issue 1. And make sure to subscribe to the journal by providing your email there as well!

And now on to the main event:

So, you may have heard, there’s a renewed skirmish in the war on the arts. This one has the potential to be a bad one, a Shiloh-style massacre of public funding, if the wrong side wins, because the first shot in this particular battle came from the guy who wants to replace the guy who is president (who, by the way, already has a not-quite-stellar record when it comes to the arts and the charitable status on nonprofits. As Alyssa Rosenberg notes here, Romney has actually hardened his position against public funding of the arts since the beginning (so very long ago) of the world’s longest primary season. He started out wanting to cut it in half, he’s now saying just cut the whole thing–the whole subsidy for the NEA, the NEH and PBS.

To point it out, that entire number, if we assume the entirety of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting’s budget is at stake, amounts to just under $800 million per year (about $150m for the NEA and NEH each, and about $500m for the CPB), or .02% of the 2012 proposed federal budget (if you want to get sad with yourself, visit that link and type “arts” into the search bar, then zoom back out to see exactly how tiny the NEA’s appropriation really is). Which basically means it makes no sense at all to spend nearly as much airtime as Romney, Palin and other GOP luminaries spend talking about cutting out the evil arts from the public fund.

So why do they?

Diane Ragsdale wrote a few weeks ago about the failure of many arts nonprofits (and their boards) to take seriously the mandate to create work that is in the public interest–that, basically, is for the good and welfare of society. That’s what nonprofits are required by law to do; we better society through service, and so are not obligated to better society through taxes. Diane’s piece notes that this isn’t often the case, drawing off of an article in the Chronicle of Philanthropy that, she notes, doesn’t directly reference arts organizations but easily could. She’s right, and I think that this blind spot, over time, has contributed mightily to the reason that Romney can get so many points (because, honestly, that’s what this is about) by shouting about gutting public arts funding.

In an essay Diane wrote for me that we published in Counting New Beans, Ragsdale gets very clear and blunt very quickly about why Republicans can beat this particular horse to such great effect.

“What does it mean,” she asks, “when government cuts support of the arts? In a democracy, the government represents the people. My sense is that the government cuts the arts when it perceives that it will not encounter a huge political backlash for doing so. The government doesn’t value the arts because it perceives that the people don’t value the arts.”

We have, inadvertently, marched ourselves into a corner, and the madman’s at the door, and our saviors have either been actively driven away or simply are awash in the apathy of a systematic lack of arts in their lives.

What frustrates me is that, even with some level of understanding that that is the case, and that we need to be trying harder to be socially relevant, socially beneficial–and even though we all deeply believe that we are making a difference–the ever-so-important articulation of why we do what we do continues to be difficult to find. And here, unlike before, I’m not talking about the general intrinsic impact work we’ve been doing with companies across the country, I’m talking about something much more fundamental: the particular reasoning behind the selection of the art we pass to our patrons.

Recently, as part of our next phase of intrinsic impact research, I have been conducting “induction” interviews with 15 or so theatre companies from across the country who are surveying anywhere from 1 to 11 shows using the intrinsic impact protocol we developed with WolfBrown for Counting New Beans. In order to off-set one of the shortcomings of the original CNB research (namely, the lack of actionable outcomes for each organization), we have started to include a deep conversation at the beginning of the process about why they want to do this research, what their goals are for impacting their audiences, and what the role of each of these particular productions is in the season and in terms of mission fulfillment overall.

These are big questions. But they should not, I don’t think, be questions that stymie people who work in the nonprofit arts, particularly artistic staff who are directly or indirectly responsible for the selection of the art. The art, after all, is the most concrete manifestation of each organization’s mission (or at least should be), and so being unable to answer where each show fits in a mission-based conversation with your audience seems, to me, problematic.

And yet, with more than a few of these organizations (though absolutely not all), this line of questioning has been very difficult. In some cases, it was like I wasn’t speaking clearly–the artistic, marketing and management staff didn’t seem to understand the underlying sentiment of the question, and were sometimes even surprised that I would be asking such a line of questioning in context with impact assessment–but even with rephrasing, often, the particulars of show selection have been murky at best. Which has been surprising to me, in part, I think, because the 19 interviews we did with artistic leaders in Counting New Beans demonstrated a varied, but consistently deliberate and thoughtful, process for show selection, and at least some conscious recognition of the role of the work in furthering the mission.

In his interview in Counting New Beans, Oskar Eustis of the Public Theater in New York notes that, as artistic director, he was in essence hired for his taste. He, to his great credit, then goes on to note that his taste alone is insufficient, and he actually talks about “problematizing” his taste to ensure that the work selected is actively and wholly representative of the particular mission of the Public. He understands, I think, that the artistic director’s role is not simply to pick good art, but to curate an affecting, transformative set of work for an audience over time.

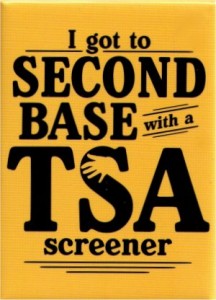

These are, from what I can see, incredibly smart, talented and dedicated people that I’ve been speaking with. They are as passionate about the arts as most people I’ve come across who have devoted themselves to this besieged profession, and they all seem to believe that the power of art is important and evident. And yet, in one of my more recent conversations, even with much pressing, we came around again and again to–instead of why this work was chosen from a mission-based point of view–why this work was chosen from a sales point of view. One show was “a lot of fun” and “great for families,” another was “the show that a guy would score big with as a first date.” To be fair, this last comment was made by marketing staff, and so the relevance of it as a marketing tool may have outweighed its usefulness as a definition of mission fulfillment. But I think that everyone in an organization should also have some understanding of the artistic director’s impetus in selecting and presenting the work in context with the mission–or else they risk misrepresenting the work to the public, and misgauging the success of the work after it is over. I worry that, as a field, we have found ourselves starving for food, and have re-appropriated our attention away from the difficult and slow work of minding the stuff that will sustain us, and that we can share in health with our community, in favor of caloric value and accessibility.

As the Economist notes in a recent poll, all hope is not lost, and about 60% of people do believe the art should be publicly funded. And I don’t intend here to argue that a work being a lot of fun is a bad thing, I’m just saying–if we are (and we are) really facing down a tidal wave of negativity from a huge swath of the population and if we have (and we have) largely squandered the good will of that population to come to our aid when, by proxy of cutting our public funding, one whole half of the political sphere seeks to eject art from the public square–aren’t we perhaps at a place now where being inarticulate about the how and why of our goodness in society isn’t just damaging, it’s suicidal?

Clay,

Great post and thanks for the reference. I like your second base analogy. I am reluctant to be completely cynical in response to your post but feel compelled to state, perhaps, the obvious. There are nonprofit arts groups whose programming is not driven by a social/artistic mission. Or if it is, the mission is so broad as to be meaningless (e.g., “To bring high quality theater/dance/music to X community”). I was giving a short lecture the other day, discussing the case of a symphony orchestra that turned itself around financially, in part by significantly increasing its earned revenue. The class discussed the implications of this strategy and tried to analyze whether this was accomplished through a deepening relationship with the community or simply a more market-oriented approach (and the implications of each of these). At one point I suggested that the concepts of “our community” and “our market” can be conflated by arts organizations, particularly those that sell admissions and rely heavily on earned revnue. Not all, of course. But too many, I fear. I think this is evident in the kinds of responses you received to your questions about why works were chosen from a mission point of view.

BTW, Nina Simon (Museum2.0) commented on Jumper today that my post on the situation at the Detroit Institute for the Arts prompted her to go scan the reader comments on the articles in the Detroit Free Press. As she astutely noted, it’s fascinating to see the arguments for and against the millage for the DIA as they are presented and debated as it’s not often that we, in the arts, solicit and hear from those that don’t support us.

OK, so what is it? What’s the value proposition we’re having so much trouble articulating?

Frank Luntz, the Republicans’ top language strategist, advises his clients to find the simplest way to express ideas using language that evokes the most favorable response among ordinary Americans. (He’s the guy who taught Republicans to say “climate change” instead of “global warming.”)

Rather than sitting around complaining about being used as a political football, maybe we should use Luntz’s strategies to our own advantage. It’s what Obama and his campaign managers did in ’08.

It would take extensive focus group research to discover the best answer, but it could be as simple as teaching ourselves to say “creative life” (which is something everyone is a part of) instead of “the arts” (which for many is an elite, exclusive realm).

If as you suggest it’s all about scoring political points, why not be smart about this and do what we have to do to stop allowing political opportunists to score points at our expense?

Thank you for this Clay. A stream of thoughts….

One

Your post reminds me of a debate/argument I had recently with a colleague/collaborator about whether directors truly considered the audience or the effect/impact of their shows (when doing anything from choosing a given script, to shaping concept/vision, to casting, etc). I regretfully ended up far toward the “not” end of the spectrum.

This conversation led me to extrapolate and begin articulating that theatre is being too often produced in spite of audience and their greater/home community. What else results in the response “they just didn’t get it” when a show is overall not landing (an embedded accusation which attempts to avail the artists of responsibility)?

Two

What Diane said (re: broad missions).

Three

I wonder whether there is a fear of losing [something] that prevents us writer’s block-style from defining, let alone articulating, our societial contribution? What if each theatre company actually articulated what type of work it was particularly dedicated to creating and why? What if we reacted to what is happening in our larger/home communities and looked to contribute to that “dialogue” as artists with our work?

Four

How do we “flip the script” of the debate instead of playing defensively into it? See Margy Waller and her work at ArtsWave re-framing the argument for financial support of the arts. See Michael Rohd and his continued query about the unique “assests” artists bring to to the table.

To my mind, we have nurtured a culture of self-interest for so long that it’s become destructive.

When we ask writers who they write for, the answer is all too often “myself.” When we ask ADs what plays they program, all too often they answer “The plays I’m interested in working on.” Too few are the theater practitioners who make plays explicitly for others, to be of service to a well-defined community. Too few are the theater practitioners who humble themselves in front of a greater idea or ideal: a useful mission that’s about more than “being heard” or “having a voice” or “making art.”

We need to demand more of each other and of ourselves. We need to stop abandoning our audiences before we even begin making theater. We need to keep them in mind, in whatever ways we can, from the get-go.

We don’t do this very often, I believe, because the financial rewards are so slim. We think: “If I’m going to suffer a life of deprivation and want, I ought to at least get what I want in SOME way.” I would put it to my fellow theater practitioners this way: yes, the economics of theater are broken, and we’re working on them… but in the meantime, while we tackle those societal inequities, if we focus on serving others instead of ourselves, to the best of our abilities, greater rewards WILL come.

Gwydion – Your comment really resonated with me because in my first arts entrepreneurship class of the semester (held last week) I ask the students “who do you make art for?” If all they answer is “for myself,” then I tell them they may be in the wrong class. We (artists/arts advocates) need to recognize that we make art in oder to put something unique OUT INTO THE WORLD. By extension, if what is put out into the world fulfills a social need and/or exists as a public good, then public funding for art makes sense. If it only gets put out there to make the organization wealthier, then, well…..

My two cents, Linda

This issue has been on my mind lately with the Detroit Art Institute levy passage and renewed focus on arts funding in the Presidential contest — not to mention the highlighting of arts funding as a political target in brilliant Aaron Sorkin style within the first 15 minutes of The Newsroom. Diane Ragsdale’s recent post — also mentioned by Rachel Grossman in her comments above — asks terrific questions about what motivated the voters in Detroit to pass the levy. I wish we had the answers to her questions. Still, we have learned a lot about how to build support for the arts with the public.

To begin — I need to clarify something that I learned from talking with Clay when we first met. My focus — and that of the research I’m writing about today — is on changing the public landscape of understanding. It’s a different focus than the programming choices that impact people who are already going to the arts. Both are important, of course. But the goals and audience are likely to be different.

Some time ago, we learned that building broad support for the arts — particularly public funding of the arts — won’t happen just because we talk about it louder or more often. Getting a new story on the front page of the local paper about the outrage of cutting the NEA won’t matter if no one is paying attention or persuaded by the information in the news.

That’s exactly why ArtsWave (one of the nation’s oldest and largest arts support organizations, based in Cincinnati) and Topos Partnership (a national strategic communications organization) invested significant resources and time to identify a NEW way of starting the conversation — one that is designed to avoid the problematic and dominant ways of thinking about the arts that get in the way of building broad support.

Trevor O’Donnell — this is the research-based value proposition you want. We did the focus groups, the interviews, the TalkBacks, survey work, media and marketing review — hundreds of conversations with residents of the Cincinnati region and the midwestern states surrounding it. And we’ve spent a couple years using the findings.

First, we identified the barriers to success in the way people typically think of the arts. We found that public responsibility for the arts is undermined by deeply entrenched perceptions. Members of the public typically have positive feelings toward the arts, some quite strong. But how they think about the arts is shaped by a number of common default patterns of thinking that ultimately obscure a sense of public responsibility in this area.

For example, it is natural and common for people who are not insiders to think of the arts in terms of entertainment. Problematically, entertainment is a matter of personal taste, not public responsibility, and perceived as an extra, not a necessity. We found several prevalent assumptions about the arts that that work against the objective of positioning the arts as a public good:

· The arts are a private matter: Arts are about individual tastes, experiences, and enrichment and individual expression by artists.

· The arts are a good to be purchased: Therefore, most assume that the arts should succeed or fail, as any product does in the marketplace, based on what people want to purchase.

· People expect to be passive, not active: People expect to have a mostly passive, consumer relationship with the arts. The arts will be offered to them, and therefore do not need to be created or supported by them. (Rachel G — I bet you have thoughts about this one!)

· The arts are a low priority: Even when people value art, it is rarely high on their list of priorities.

Perceptions like these lead to conclusions that government funding, for instance, is frivolous or inappropriate. Even charitable giving can be undermined by these default perceptions.

Our investigation identified a different approach, one that moves people to a new, more resonant way of thinking about the arts.

What is it? That the arts have benefits that ripple throughout our communities. Theaters and galleries mean vibrant, thriving neighborhoods where people want to live, work, and play. Music, museums, community arts centers and more mean people coming together to share, connect and understand each other in new ways. These benefits are both practical and intangible.

However, we know that it will take time — and many partners across the nation — to move this way of thinking to the forefront of people’s minds. Eventually, we want this to be what people think about first when someone mentions the arts.

We want to win these policy fights in the long run. And the Topos research shows that to do this we need to turn on and build up the new way of thinking about public responsibility for the arts — among all citizens, not just our current consumers.

We’ve learned that people already believe in the ripple effect of benefits like vibrancy and connection. Even if they don’t experience these things in their own neighborhoods or at events they attend, people understand that having (more of) these benefits are good for everyone in the region.

While nuances and emphases will vary from context to context, the essence of a public conversation is that the same themes echo from a variety of sources, in a variety of voices. When legislators, business leaders, community leaders and so forth all take in the same core messages – and in turn repeat them to their own constituencies – the resulting echo chamber can begin to transform the accepted common sense about the arts as a public good.

You can read the full report and more at http://www.topospartnership.com/project/arts-and-community/

Just this week — at an Americans for the Arts panel at the Republican convention, we saw an example of how the research findings work. A news article in wide circulation on the internets today reports that Mayor Scott Smith (R) of Mesa said: “There is a direct connection between the health of the arts and culture in your community, and your ability to grow economically. People want to live in a place that is vibrant, that is growing.” And he noted that this remains true in tough times. The news article goes on:

“Smith has been successful in maintaining the center, along with other outlets for the arts, while in office.

That has come, according to Smith, at the same time the city has had to deal with financial issues. He said he faced a $65 million deficit when he took office four years ago.

“Of course you start cutting,” said Smith. “The first things you want to cut are the frivolous things. Arts and culture are considered by some to be frivolous.”

But not by him, Smith said. And not by residents of Mesa who provided their input on the value of arts and arts education. Because of that, he said, the city has tried to cut as little funding for art-related programs as possible.

Smith sees the lack of opposition to his re-election bid as a vote by Mesa residents that they approve of his handling of the city’s budget.”

We need a lot more articles like this. And local leaders too!

Margy: I’m very much looking forward to speaking with you about this on Thursday. We not only need more articles like this, we definitely need more moderates (both Republican and Democrat) like Scott Smith who understand that arts and culture are not only economic drivers, but community drivers and who have the foresight to engage leaders like Cindy Ornstein of Mesa Arts Center who can build partnerships between citizens, artists, and government.

Perhaps a way to more effectively articulate the arts-as-public-good argument is to look at the arts and civic engagement, the arts as community cultural development, and, as has been the argument in the past, the arts as educationally beneficial. In other words, “fight on the ground we can win.” (see http://creativeinfrastructure.org/2012/06/20/its-not-the-economy/)

So many provocative and productive themes in this conversation, y’all.

I’m struck, first, by the atmosphere of anxiety in which it is trying to taking place. The spector of the threat to public funding and nonprofit status for the arts in this country has created a culture of self-censorship among many leaders and practitioners. To even raise these questions in sunlight is, it would seem, to invite the apocalypse. There is some truth to the concerns about the strength of our sector to withstand the rhetorical bullying from politicians and pundits looking to score easy points with their puppetmasters. But I cannot believe that, in such times, hiding from facts and banishing questions is the better path. So, good on ya for holding the space for that.

Second, I am so happy to be directed toward your work, Margy Waller! It is such a help.

Diane’s original post raises a whole host of troubling questions about what comes next. (You have the knack, Diane, I gotta hand it to you!) In particular the question of whether this is only a tactic for the “first responder” and only EVER for the largest fish in any metropolitan pond. But for the moment, I want to linger in what the public meant in voting “Yes” and try to understand from that what is expected of us. It is, in a sense, a focus group of millions.

I often use this Zelda Fichandler quote, which she delivered as part of her testimony to Congress during the hearings that ultimately extended non-profit status to theaters in this country. “Once we made the choice to produce our plays not to recoup an investment but to recoup some corner of the universe for our understanding and enlargement, we entered the same world as the university, the museum, the church and became, like them, an instrument of civilization.” There’s the value proposition and the responsibility of nonprofit status: I will endeavor to “recoup some corner of the universe for our understanding and enlargement” through my choices day to day, moment to moment, project to project, and job to job. I can imagine that, on some fundamental level, this is what the voters in the DIA story are hoping for, and expecting from, the museum in return for their extraordinary vote of confidence.

I resonate with Gwydion’s correlation of our predicament to the cult of the self that defines our times. I am not moved by solipsism, whether it is an institution, an artist, or a project that is afflicted with the malady. I don’t think it is enough to say “because I want to” or “because I need to” or “because it interests me”. It may be enough to move one to make the next thing, but that next thing may not be a necessary thing. If we do not start by looking outside ourselves, if we do not proceed from the value proposition—from the expectation that we are aiming to recoup some corner of the universe for our mutual understanding and enlargement—then we are not in synch with the purpose of the nonprofit status, period. Go ahead. Make work that is first and foremost about your own survival, your personal pleasure, the enrichment or advancement of you and yours. But don’t ask the public to subsidize you for it.

And I know we dwell on a slippery slope of subjectivity here at all times. But still, I see the corner of the universe that I, personally, found recouped on any number of nights in the theater that reached me, in my seat, and pulled me toward my own humanity in a way that entertained, elevated, and let me be touched by things I’d never touched about my neighbors, my planet, my time. And I know that wasn’t left to chance—someone intended, from the outset, to take me to empathy’s door. And I want to ask for that “aiming to recoup some corner of the universe” to always be the purpose, always be the attempt. If we, the tax payers, are to make this a priority, to direct our support toward the arts, this seems like the least we should be able to expect of them.

Margy has it so well put here: “Music, museums, community arts centers and more mean people coming together to share, connect and understand each other in new ways. These benefits are both practical and intangible.” Is it too “proscriptive” or “fencing me in” to ask that any art that asks for public support should have at its heart the intention to bring people together to share, connect and understand each other in new ways? If you want to make work (as an individual artist or as an institution) that is principally and primarily about following your own drummer– principally about YOU– than perhaps your business model should be something other than public funding. And IN PARTICULAR, if you want to make work that is principally (and therefore narrowly) about your own survival (individual or institution) then we really have to ask whether this is something that aims to recoup some corner of the universe for our understanding and enlargement as a people.

There’s a part of your set-up here, Clay, that is a bit of a “straw man” thing. You use extreme examples designed to drive your point home though there are many examples of people and institutions that have their priorities in order. And it will make it easier for people to dismiss your questions here. “You’re being extreme. Most of us are not like that. Most of us are just good people trying to do the best we can for this form we love. And you put us all at risk by harping on these outliers.” But I sympathize with you. I, too, have had too many conversations with both artists and institutional leaders where the call to connect clearly and regularly around mission, purpose, and impact was met with blank stares or dismissed as divorced from the day to day reality on the ground.

I am glad you cite Oskar Eustis’ notion of “problematizing” his taste. It is an important concept and something that I find both instructive and challenging in my own work. I am not so sure he was, actually, hired primarily for his taste, though. He was hired for his intelligence, and his bedrock belief in the mission and purpose of the Public Theater as demonstrated throughout his entire career leading to that moment. I am just guessing. But what is most compelling to me about Oskar is his passion and his unshakable conviction that he is the leader of the New York City public’s theater. He knows it is not about him. And he knows, and can speak movingly of, what it IS about.

David, you asked: Is it too “proscriptive” or “fencing me in” to ask that any art that asks for public support should have at its heart the intention to bring people together to share, connect and understand each other in new ways?

In short, I say: no it is not.

Art poses a hypothesis, a view of the world and then steps back and makes room for reaction. It is the start of a conversation. It is a part of public dialogue, civic discourse. It is human. It is empathetic. And theatre as an artform in starting conversation?–ideal. It does all this in a public forum, live, with makers/doers and watchers/receivers sharing the same breath. Art supported by the public should aim for a greater good, this higher end. Telling interesting, moving stories on stage?–its not enough.

I am reminded of two quotes/ideas.

Eric Booth defines entertainment as “what happens within what we already know” and art as what “happens outside of what we already know.” “Inherent in the artistic experience,” Booth says “is the capacity to expand our sense of the way the world is or might be.” He calls it an “essential birth right” to “expand our sense of the possible.” And American culture works actively, aggressively against it.

(3min, 23sec version: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dlyrn_wVzA)

Federico Garcia Lorca wrote:

“The Poem

the Song

the Picture

is only water

drawn from the well

of the people

and it should be given back

to them in a cup of beauty

so that they may drink

and in drinking

understand

themselves.”