In June 2009, I was briefly in Washington, DC, visiting friends right after that year’s Theatre Communications Group conference in Baltimore, MD. I was in their spare room, small and tightly packed, and it was humid because it was DC in the summer, and there was a CPU humming in the corner and various lights blinking under the desk, and I was on West Coast time still, I think—so I was checking Facebook. Back then, I got a lot of different feeds—many more people than I see now, thanks to Facebook’s mysterious algorithms—and as I was scrolling down I saw a posting pop up from a friend of mine who I knew from San Francisco, a woman about 20 years older than me. Well, not from her, not really—it was from her son, and the posting was to let everyone know that she had been in a car accident in West Africa and that she was in the hospital, and that her husband, who I was also Facebook friends with, had been killed.

My breath caught. I didn’t know her or her husband very well, not really, certainly not enough to be one of the first people to know about a horrific accident that had disrupted one life so profoundly and ended the other so suddenly. Nevertheless, I found myself drawn to her husband’s page, to her page—rolling back through their feeds, back past the mourning and the sadness, all of the exclamations of distress from friends spread across the world, tripping backwards through the narrative of their trouble to the moment right before anything was wrong. Him, writing one quick sentence about how wonderful it was that his wife was joining him on the African tour. Her, posting something innocuous on another friend’s wall. And then the messages from their son, and then the sadness.

I compare that moment, threading backwards through the feeds of ten, twenty, thirty people digitally crying out, the strange companionship in that sort of sharing, with the wracking, deep, immovable weight of sadness that crushed me years earlier when I found out my grandfather had died, also in a car accident, also with my grandmother by his side, surviving. A curve in a highway, a descending hill and a bad decision by an old man, a flipped car, a box of old family photographs releasing like birds into the wind, a parakeet in a damaged cage singing by the side of the road. When I found out about that moment, in a strange house away up north, my parents far away and shocked and making plans to cross the country and wondering what to do, all I could do was howl and turn inward and cry until I had no more water in me and my head throbbed and my eyes shut.

Mourning has shifted, in a way, or at least has expanded, flattened out. We mourn in company now, just as we celebrate in company, break up in company—all of it chronicled with a specificity that is startling in its clear, concise black text on a white background. There, in that innocuous white break between updates, that right there is the moment when it happens. That’s the transformation. That’s the instant of impact.

We, as humans, innovate ourselves into new places all the time. And in this case, rather than morbid curiosity, I think when I read through these threads I am responding to this new specificity, this common understanding—the translation of the personal to the communal. And while this, yes, is about grief and death and sadness, it doesn’t need to be, and I find myself equally attuned, though less believing of the genuine sentiment, to the fifty birthday wishes from people I haven’t seen face to face in fifteen years.

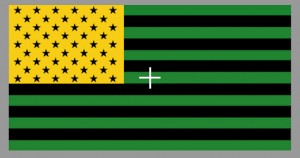

There is something precious (precious as in valuable, not precious as in quaint) about the ability to so clearly and specifically see the afterimage of life. It’s inexact, of course, but the floating flag in front of us, hazy and blurred as it might be in the blank white space, is the remnant of our attention. It is not perfect, and even as my sadness at my grandfather’s passing is unfathomable and unknowable in a way, there is now something, the echoes around the space between. The before, the after, the wonder of that moment in the midst. As schoolchildren, we are all at one point or other asked to stare unceasingly at an orange, green and black facsimile of the flag, holding our lids open until our eyes swell with tears, and then to close them, turn to the white wall, and see what our retinas and brains have made of what was there.

And so it should be in art. This is not to say that everything needs to be deep, or brooding, or steeped in sadness or significance. But it is to say that the best art, the best of what we do, is memorable—and that that memorableness is not a side effect; it is the goal. We make a difference in people, with our stories, and whether that difference is elation or defeat, glory at something new or wonder at something achingly familiar, we should pride ourselves on that effort. And we should take every step we can towards maximizing that effect, understanding that effect, measuring that effect.

Today, I am officially the editor of a published book. It’s called Counting New Beans: Intrinsic Impact and the Value of Art, and it’s about many things, but for me, personally, it is about this, all of this: my obsession with the afterimage of what we do, my frustration at its departure from the center of how we talk about and value ourselves as artmakers, my need to understand where we’re going if we are to keep afloat. It is full of voices that are articulate and strong, definitive in their understanding that things need to change, that the way we talk about our work, understand our impact, reach our goals needs to be reevaluated. And it is the hardest and most rewarding piece of art I’ve ever had the pleasure of helping create.

Alan Brown and Rebecca Ratzkin of the research firm WolfBrown detail, with over 80 color graphs, exactly how specifically we can tell the impact we’re making in their research report, “Measuring the Intrinsic Impact of Live Theatre.”

Diane Ragsdale argues passionately that we have gotten ourselves to a dangerous place, right on the cusp of irrelevance, and that we make have to take drastic measures, in “Creative Destruction.”

Rebecca Novick dissects deep, searching interviews with five major artistic directors from across the country to try and understand how we could have moved the audience so far from the center of this audience-reliant enterprise in “The Importance of Beginning.”

Arlene Goldbard struggles with patron interviews, Plato, and the things we tell ourselves about our patrons in an effort to understand what makes the perfect patron in “Symposium.”

And intermixed, twenty-four artistic leaders and patrons talk about their relationship to art, memory, joy, companionship.

It’s always hard, when you write as much as I do, to find yourself inarticulate. And of course this sentence is buried under 1,000 words that belie that adjective, but still—I cannot really express how proud I am of this compilation, how strongly I feel these thoughts of these people need to be injected into our field-wide conversation, how much I hope we can truly, together, begin to change the way we value and evaluate art. Nor how grateful I am for the foundation and government support, the hard work of our partners, the dedication of the companies involved, and the drive of so many to let this work see the light of day.

For me, now, Facebook faces forward, toward my daughter, and I am now one of those insufferables who updates the world on an infant’s accomplishments. It is a chronicle of memories, and I scroll back, I scroll back, I scroll back fourteen months, past running and walking and crawling and eating and rolling and smiling and burping and yowling through the night, islands of black text memory in a stream of white, blazing life. And then I’m there, and it is December 2010, and I can see it, literally, there on the screen—white walls with a brown wooden wainscoting, a shimmering blue hospital curtain backlit with sunlight, and my head bent downward as I hold my new daughter close to me and look at her beautiful face.

That is the transformation. That is the instant of impact. And before that, what? After that, what? A breath. A moment. The tumble of our world, the unfathomable complexity of living. White space and a life, a memory: the afterimage.

***

Because I can, here’s my moment to shamelessly plug the book. It’s beautiful and awesome and I hope you will consider buying it, or at least reading the free excerpts, including the executive summary of WolfBrown’s research report, at http://www.theatrebayarea.org/intrinsicimpact. I’ll also be touring across the country presenting the results of the work, so check that website for the tour schedule as well.