I have a friend who is getting his Ph.D. in linguistics by resurrecting a dead Native American language. Working with one member of the tribe, and drawing mostly from hundred-year-old documents that attempted to transcribe a non-written language that has since died, he is recreating, based on educated guesses, other similar tongues that have survived and, well, I don’t know what—he is recreating a lost language from scratch.

I was reminded of this effort as I listened today to the “Afterword” podcast from Slate, in which their culture editor June Thomas interviews the author of a nonfiction book. This week’s book was called Rez Life, and it was by Native American author David Treuer, who talked about his life, experiences, and the precarious nature of Native American sovereignty inside America. Tribes, of course, have had an extraordinarily difficult time in the U.S. since the founding of the country and before, and much of their history is marked by whatever the fight of the moment with the government was. At one point in the podcast, Thomas asked Treuer what he thought the next big fundamental fight was going to be for Native Americans, and he lit on this idea of the re-appropriation and resurrection of language. And what he notes is that the re-appropriation of language isn’t just about language—it is fundamentally about culture.

As Treuer says:

“It’s not practical [to resurrect a language] in that you’ll be able to use it to buy toothpaste. But it’s practical in the sense that if you want to retain some sort of tribal autonomy, if you want to make a strong case for our continued sovereignty, you also have to take into account a cultural case. And language is one of the ways in which culture is expressed and promoted and carried on…Economics is important; there’s nothing limiting about being Native, but there’s a lot limiting about being poor. But what I’ve noticed and what I think of as being the next big fight is this return to tribal languages and religions. Centuries of neglect of cultural knowledge and tribal languages and derision aimed at these holdouts—these “traditionals,” who are talked about as being not as bright, not as forward-thinking, not modern, stupid. These were things leveled at traditional monolingual, sometimes bilingual, speakers of their native languages; practitioners of their cultural lifeways. This is turning around.”

We’ve assimilated too much, the buzz seems to be, and we want to find our way back to ourselves.

This spins me in two different directions. The more obvious one is toward a celebration of the return of “culture,” in ways both artistic and non-artistic, to the center of a society—especially when that effort is viewed less as esoteric and more as salvation from a sort of oblivion. As I watch American society-at-large slowly strip away traditional artsmaking and viewing from our day-to-day lives, I see shadows of a future in a century or two where such traditions are revived from the dead in an effort to salvage a society in need of salvaging. Which is, I guess, weak tea as far as consolation goes, but is an interesting shift, nonetheless.

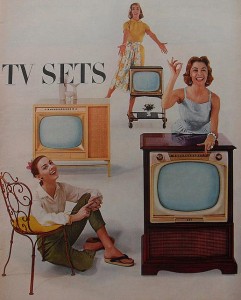

But the other direction Treuer’s thought takes me is less obvious, and centers around the current and on-going effort to “modernize” theatre, classical music and classical dance in order to make them “relevant” to more people, more “participatory,” more “on-demand.” I say this as someone who has written a lot about how to try and take steps toward fulfilling that effort, but as I reflect on Treuer’s interview, I am given pause. I, more and more, find a lot of that discussion nerve-racking. This past Monday, You’ve Cott Mail ran a “Digitization of Live Performance” edition and included stories from the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian and AP, among others, all highlighting efforts in the arts to broadcast live performance. These articles, full of wonder at the opportunity to do webcasts and simulcasts of theatre and music, seem to have forgotten that broadcasting live performance is what soap operas and early sitcoms did for fifty years, and that if you’re talking about such things you’re really just talking about, well, television.

The rise of technology that has allowed for easier creation and consumption of art has been a vexing and intriguing problem for arts organizations for a while now—a lot longer than the rise of television in the 1950’s or the advent of the personal computer 25 years ago. In 1935, Walter Benjamin wrote the famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which, in the particular, concerns itself with the fate of the fine, formerly-non-reproducible arts like painting and theatre in the face of new technologies like photography and film, and in the abstract dissects the live arts experience in an attempt to understand what might really go missing in a world of reproductions.

Rolling forward 80 years, one might now think instead of “The Work of Presentational Art in the Age of On-Demand Technological Empowerment.” Not as catchy, perhaps, but when Benjamin writes of the stage actor versus the screen actor it echoes today, even if in a more gradated, though strong and obvious, form. The implication, per Benjamin, is that the camera allows an increased distance from the actor and art, and places the audience in the role of critic.

This troubles Benjamin because of a concept called “aura” that he proscribes to live events, which he defines as follows:

“[Aura is] a most sensitive nucleus—namely, its authenticity…the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced.” For Benjamin, this is the germ at the center of the live event, the essence of which cannot be transmitted through technology—whether photography or film or, one presumes, digital interfaces like YouTube. With the advent of film, Benjamin explains, “for the first time…man has to operate with his whole living person, yet forgoing its aura. For aura is tied to his presence; there can be no replica of it.”

What we give up there, of course, also allows us to gain. The advent of film, just like the advent of photography, makes proliferation of whatever portion of the art we can transfer to the new media much easier, dissemination more expansive, viewership more diverse. The analogy that comes to mind for me is something like the antidepressant Prozac—a drug developed at the cost of about $900,000 that was sold at a mark-up to cover (and more) that initial cost, but that lost its exclusive patent in 2001, leading to many cheaper, generic alternatives, and to a proliferation of those alternatives into whole new segments of the population. The difference, perhaps, is that those generics miss only the brand name, not the effectiveness of the drug, whereas with live art that is arguably not the case. In a way, it is the inability to transfer the visceral impact of a live theatre experience to film (the effectiveness of our “drug”) that has been the barrier to effective consumption on a mass scale. There’s a reason that good movies and great television don’t just look like filmed stage plays. What we do works in a room. It looks like shit on a screen. And perhaps that’s exactly Benjamin’s point.

Looping back to David Treuer and his efforts to maintain Native American culture, at another point in the interview, Treuer talks about how “blood quantum,” the process by which eligibility and benefits in many Native American communities are apportioned based on what percentage of Native American blood is in a person, was a policy that the United States government liked because they thought that ultimately it would mean that all the Natives, having over a few hundred years intermarried with whites, would essentially be so watered down, blood quantum-wise, that Native Americans as a concept would simply cease to exist.

Trying to push live media into a digital world feels more than a little to me like watering down our blood—which of course is an awkward thing for me to feel, because I do strongly believe that theatre and classical music and classical dance do need to find ways to innovate their way into more popularity. But I don’t want them to lose their specialness, their, to use Treuer’s word, “sovereignty” in the process.

If, as Benjamin says, the aura of a live arts experience is unable to transfer to a facsimile of that arts experience, is there still value in the facsimile? If, with mediation like a television or a computer screen or whatever, the presentation of the aura of that experience from artist to audience is lost—if, in a way, the “culture” of presentational live art disappears without the particular “language” that only is transmissible through breathing the same air and hearing the words or music echo in the same room—where does that leave us?

What I’m left with is the unsettled feeling that, before we go out and innovate ourselves into second-rate television, we need to understand what the unchangeable constants are of our forms—and that we are foregoing that crucial conversation out of fear for basic survival. What makes what we do, what we do? What do we turn into if we let it fall by the wayside? What makes “theatre” no longer “theatre?” This, essentially, is the flipside of mission—the understanding not of what we were created to do, but of what the peculiarities of what we do actually do to people, and how important those particular aspects are. David Treuer makes the distinction, here, between “culture,” which sits at the core of you, and which you change only under peril of ceasing to be what you are, and “identity,” which is changeable and able to be manipulated.

“Your culture is something that you don’t choose,” says Treuer. “It’s this contested, strange, nebulous, often times unconscious, habitual way of being. You don’t choose your culture as much as you choose your identity. You are what you are.”

In her most recent Jumper post, Diane Ragsdale exhorts us to move toward reform, quickly and decisively. She’s talking about form, and organizational structure, and elitism and accessibility, and all of the stuff that we are all so worried about right now. It’s why Nina Simon’s Museum 2.0 is all the rage, and why WolfBrown is distributing papers on “participatory art” and “audience engagement.” It’s the zeitgeist of the moment, in part because it has to be–and I’m on board with all of it, with this one caveat: we must do all of this while remembering the core of what we are.

“If our goal for the next century is to hold onto our marginalized position and maintain our minuscule reach—rather than being part of the cultural zeitgeist, actively addressing the social inequities in our country, and reaching exponentially greater numbers of people,” Ragsdale says, “then our goal is not only too small, I would suggest that it may not merit the vast amounts of time, money, or enthusiasm we would require from talented staffers and artists, governments, foundations, corporations, and private individuals to achieve it.”

I’m not sure I can simply agree, much as I might want to. This, more than anything, reminds me of Veruca Salt, forever simply wanting more without pausing to ask whether that was going to truly get her someplace she wanted to be at the end.

In the southern rainforests of India, a sect of Brahmins has been singing the same songs for thousands and thousands of years. They pass the songs downward through the generations, taking care that the exact length, intonation, order and speed are maintained. It’s a very, very careful process, painstaking and inefficient, but it’s also absolutely necessary, because the songs they sing are so old that they’re in a language that no one understands anymore. The music has literally outlived the knowledge of the words, making the singing a true act of faith and the passing down of its non-literal attributes fervent and difficult. The art is the only aspect of a society that has maintained through the generations, the strong bone strung like a lattice with fragments of a time that has disintegrated away.

We are not making television. We are not making music videos. Yes, listen to Diane, yes, listen to Nina. But listen with your hand on your own pulse, knowing who you are. We can make these arts more accessible within the confines of what they are—we can play with our identity without giving up our culture. And in some form, I believe—if we can do that, just that—this art will endure.

Clay,

I greatly appreciate what you’re struggling with here. I think it is what draws many of us to theater, something authentic and I like to say tactile–a word I steal from Benjamin. I was at the theater the other night watching Universes AMERIVILLE, and there’s no way to reproduce that, to feel those bodies in a room and to know that the work and the bodies and the performances are completely intertwined. It’s electric.

But it’s important to note that Benjamin was struggling with a very particular ‘modern” problem that plagued so many critical thinkers of that time and is even more relevant today–the idea of the death of the author, the idea that one’s creations could be replicated and distributed at will and that in an age of reproducibility where do things originate — in the understanding the ability to identify the origins=work that is more palpable and authentic.

He says in “On Some Motifs on Baudelaire”

“It is not the object of the story to convey a happening per se, which is the purpose of information; rather, it embeds it in the life of the storyteller in order to pass it on as experience to those listening. It thus bears the marks of the storyteller much as the earthen vessel bears the marks of the potter’s hand.”

Benjamin knew the problematic nature of origins and the idea of the “auteur” but he clung to the notion of the idea of the tactile, the trace of the origins using the metaphor of the potter’s hand.

Benjamin and Adorno and other members of the Frankfurt School were trying to make sense of how to define humanity in the wake of Nazi Germany and to take from Judith Butler–they had to identify “Bodies That Matter.” Your use of Native American culture and language is provocative in this context–the idea that blood defines culture/ DNA is compelling and perhaps also frightening. Feminism has struggled with this idea of the essential nature of the body for a few decades now– efforts to define what is female through breasts and menstrual cycles, and birthing seemingly provides something incontrovertible about a culture based in gender, but the minute the “essentials” are defined a ton of feminists don’t connect at all to this definition of their culture and in the late eighties and early nineties huge battles broke out about whether female sex workers were victims of their gender or empowered by it.

But back to your point about art. I think the train has left the station about this question of originality. I’m thinking about an artist like Cindy Sherman who makes certain that when photographing herself, the context can have nothing to do with who she thinks she is or how she sees herself. She exposes the idea of the photograph as capturing the true self, as something only a small step away from the original. And this is the truth of our culture now and it’s freaking us all out because if we can’t comfortable identify ourselves and our contribution to our art, if we can’t take proper credit and control our our work and our identity is distributed and disseminated, well then we have to face daily (not just in philosophical textbooks) the idea that our aura is fading.

For me the question itself has to fundamentally change–in your formulation I think you’re saying –how can we hold onto the “I” in what is becoming a fundamentally “we” culture? I wonder if we tweak that a bit to consider how we can find and define a new version of “I” inside what feels like the fait accompli of the “we?”

There is no substitute for experiencing performance art, of every kind, in person and up close. Unfortunately the cost of the large scale theater, symphony, opera etc. keeps increasing. High costs, lack of traditional education and the proliferation of alternative entertainment leads to decreasing audiences. Delivering performance art through various media lowers the cost and an increase the audience. It may lead to people wanting to experience the “aura” (and it may not). Another option is to produce large quantities of small scale performances, at much lower costs, through-out the community. This has the potential of keeping the “aura” alive and reminding people of its unique value. If the large performance arts organizations want to remain relevant, they not only need to expand their media delivery options, they also need to learn to think small. Any institution has to remain relevant if it is to survive.

Clayton:

Thank you for calling my attention to your post and to Polly’s comment. It seems that the arts are in a constant struggle between preservation and innovation. In an ideal environment, both would be equally valued and both would be equally funded. The filming of live performance is not necessarily always about the distribution or preservation of that performance, however. Polly’s example of Cindy Sherman is a good one; an example of someone who is both an innovator and a reproducer.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot since seeing “Pina,” Wim Wender’s extraordinary 3D film documentary on Pina Bausch and her work. I hesitate to even call it a “3D film documentary,” however, because I think what it is is a totally new thing. It is a new way of seeing and experiencing dance. It is not live and it is not film. It is not meant to preserve Pina Bausch’s work nor to distribute it, although it does that too. It is “authentic” in and of itself. Whether or not it is “tactile” is interesting to consider given its 3D-ness. I felt that the experience of it was.

My arts entrepreneurship class reads Anne Bogart’s book “and then, you act.” The chapter entitled “magnetism,” which we just read as part of a segment on marketing, describes seven human compulsions that theatre (and, I would argue, all of the arts) fulfills. One of these is empathy. There is a fear that when we mediatize live arts like theatre or dance we will lose that empathy. However, we can still experience that empathy for and with the others in the audience. When a work of art is as extraordinary as Wenders’, it incites empathy toward humanity writ large. [If you haven’t seen it, rush out now and get a ticket!]

This morning, I read a blog post about the psychology behind the sudden rise of Rick Santorum. (http://www.forbes.com/sites/toddessig/2012/02/19/santorums-rise-and-the-shocking-power-of-future-shock/) The author (full disclosure – he’s my brother) contends that Santorum’s rise “is being propelled, in part, by his tapping into a deep longing for a simpler, less technological time.” It’s scary to think that we might lose the empathy we experience in the theatre if performance is distributed solely via digital recording. (But not as scary as Santorum for president.) Truly innovative artists – and I want to underline that I mean artists, not arts organizations – will solve this by creating the something we haven’t even thought of yet. It’s our job on the organizational side to provide environments in which both innovation AND preservation happen.