I was at the Americans for the Arts conference in San Diego this year, however briefly, I was able to sit in on the wrap up session, in which a woman whose name and title I didn’t catch gamely trooped around the room cajoling participants into discussing their best takeaways from the conference sessions.

People were reticent, exhausted, as they always are at the end of the conference, and it was generally speaking a thankless job for the moderator—but she did draw out a couple of energizing comments amidst a bunch of tired faces waiting for Ben Cameron and a mariachi band to (separately) close things out.

At one point, a large late-twenties guy with a beard raised his hand. The moderator went over to him, and he took the mic from her (at which point I thought to myself, “Uh-oh.”) and said (and while I’m paraphrasing here, this is close enough to what he actually said to make me uncomfortable all over again):

“I’m a Next Gen Leader, and I have a couple things to say to the Boomers who won’t retire. One, your emails are too long and I. Don’t. Read. Them. Two, get out of the way—it’s time to retire!”

The room was still after this, though I would hope the minds in the room were not. Mine certainly wasn’t, though honestly it was mostly overwhelmed by a clenched stomach and the strong feeling that that was both totally rude and completely disrespectful. It’s the kind of thing a person might think at the end of a frustrating day, if one were so inclined, but it’s not the type of thing that you speak aloud.

My inner WASP was mortified—as my husband will attest, in my family we have a very structured way of dealing with unpleasant subjects, which is to say we build a structure around the unpleasant subject until it’s less visible. We speak in nuance, or not at all, we sideline discomfort and prefer to nudge rather than shove. We bide our time—which of course is not the same thing as not being ambitious; it’s just not being obvious. My mother and father, both successful business people with long, long careers dealing with lots of difficult people, nevertheless taught me that respecting those around me, and expecting respect from them in return, was paramount and always imperative.

So that guy’s comment made me feel gross. But here’s the thing: it made me feel gross for the fact he was saying it in a crowded room, full of the very Boomers he was referencing. It didn’t make me feel gross because I necessarily thought it wasn’t true.

The Center for Cultural Innovation has just released a report by Anne Markusen, funded by Hewlett and Irvine, called Nurturing California’s Next Generation Arts and Cultural Leaders, and it makes for a fascinating read, especially for someone like me, who grapples with feeling like I have so much to learn while at the same time feeling sometimes frustrated, stymied and undervalued in my work. I recommend you read the full report, but if you’re feeling like some CliffsNotes, what follows is a basic summary of the findings.

- The overarching thesis of the report is that Next Geners care very deeply about what they are doing, and are generally satisfied with (even proud of) the impact and value their jobs have to society, but generally perceive themselves to be undervalued, undertrained, unmentored, overstressed, and underpaid. Whew!

- Overall, respondents were very optimistic about their ability to make a life in the arts, though often they didn’t see themselves making that career in the organization where they were currently employed. In general, in fact, there seems to be a trend toward lateral mobility—climbing by jumping from vine to vine as there is space instead of waiting for the guy above you to jump off into the abyss.

- As has been the refrain over and over for the past few years, Next Geners are values-driven people – they want to be doing something that matters to the world and that they enjoy. That said, values-driven employment satisfaction only goes so far, and over half of the respondents felt they were overstressed, underpaid, unable to network and unable to feel job security. Only half of all respondents were salaried.

- Next Geners express a lot of frustration at the structure of organizations, which they feel leads to an inability to advance and a mismatch between aspirations and reality. They see a lack of nurturing from older leaders, whose attitude is often interpreted as disrespectful and dismissive of ideas, and feel generally that the organizations in which they work lack “strategic vision, financial realism, community awareness and diversity.”

- While Next Geners are getting promotions, they are more likely to get a title change than a salary increase.

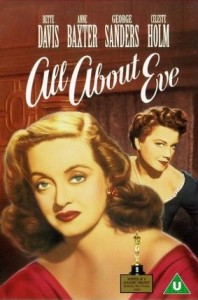

In their preface to the study, Marc Vogl from Hewlett and Jeanne Sakamoto from Irvine call the report “a wake-up call to anyone who cares about the arts in California.” And I guess in a way it is, in that it is the unfiltered angst of the coming generation, packaged for public consumption. But here’s my issue: I think this makes us Next Geners sound like a bunch of whinging brats. I imagine a similar confessional report conducted on Boomer current arts leaders might have seemed a bit whiny too, but all the same I have a lot of unease around this conversation. Basically we’re saying, albeit more politely than the crank at AFTA, that we’re smarter, we’ve got better ideas, we believe in the value of this organization and don’t think you understand how to help that value shine, and we’re really frustrated that you’re still here—oh, but we’d really love some of your time and attention. It’s just a little All About Eve, don’t you think? Like this part, for example:

Addison DeWitt: What do you take me for?

Eve Harrington: I don’t know that I’d take you for anything.

Addison DeWitt: Is it possible, even conceivable, that you’ve confused me with that gang of backward children you play tricks on, that you have the same contempt for me as you have for them?

Eve Harrington: I’m sure you mean something by that, Addison, but I don’t know what?

Addison DeWitt: Look closely, Eve. It’s time you did. I am Addison DeWitt. I am nobody’s fool, least of all yours.

Eve Harrington: I never intended you to be.

Addison DeWitt: Yes you did, and you still do.

Eve Harrington: I still don’t know what you’re getting at, but right now I want to take my nap. It’s important…

Addison DeWitt: It’s important right now that we talk, killer to killer.

Eve Harrington: Champion to champion.

Addison DeWitt: Not with me, you’re no champion. You’re stepping way up in class.

This isn’t just demure propriety on my part, either. Yes, I absolutely have frustrations about my career in the arts—I took the survey, and I can see some of my comments made it in. I’m frustrated at my salary, frustrated at a difficult organizational structure that ends up meaning I don’t have enough staff or time to do everything I’m supposed to do. But I’m not so naïve as to think that simply by moving up in the hierarchy all that’s going to get solved—nor am I so parsimonious as to think that those higher up in my organization either don’t see those frustration points or don’t care. They were all frustrated young professionals once, too. Which isn’t to say that there’s not value in people of all ages and levels in the hierarchy seeing this report and thinking on what it means now and in the future.

In the introduction to the proper report (page 10 of the PDF), Markusen says the following, which is really at the crux of the issue:

“A number of recent studies have predicted a massive inter-generational management transition looming in the nonprofit sector due to top leader retirements. The transition is likely to create long-term weakness and instability in many nonprofit organizations if not addressed with some urgency…This impending leadership deficit may have even greater impact in the relatively young nonprofit arts field, still generally characterized by founder-leaders who have “learned on the fly” and by few training and professional degree programs, low paying staff jobs, long work hours and inadequate advancement opportunities. The generation of young leaders who sparked a powerful nonprofit arts movement more than thirty years ago are now seasoned and accomplished managers and strategists, and m any wonder who will become the leaders for the future.”

A few years ago I was watching a panel, I think—I can’t remember where, but it was on leadership transition. A managing director of a major theatre was asked about what she thought the qualifications should be for Next Gen leaders moving up into leadership positions, and she paused and then briefly told the story of how she herself became a leader in the arts. At the end of it she said:

“But, you know what? Things are a lot harder now, a lot more complex. And I don’t think, if my younger self were to walk in the door now for my job, I would have hired her. You just need so much more now.”

I don’t think that’s true—I think she just, like all of us, didn’t realize how hard it was going to be when she started, so she didn’t have the fear. Like the person who is new in town who unknowningly wanders through the bad neighborhood, but only gets fearful after someone else tells them how lucky they were to survive, part of moving up is having the hubris to believe you’ll be able to succeed. The truth is that, as I’m learning from being a new father, it turns out that our parents never really had it nearly as together as they made us think. Arts leadership, like parenting, is as much about being open to learning from others and making mistakes, reflecting on the lessons you picked up when you were younger, and preparing to be unprepared for what’s coming.

One of the last comments at AFTA, maybe a half hour after “your emails are too long,” was from a young black woman who stood up and said, “I just want to respond to that guy who told our bosses to get out of the way. And I’ve got to say, our bosses deserve a lot more respect than that. I want to thank all of the people who have guided and mentored me, and taught me the skills that are allowing me to succeed now.”

It’s always that balance, isn’t it? Because I’m fairly certain that woman has that same ambition in her as the guy—it may just be that she’s learned the most important lesson of all. People don’t move because you tell them to move. They move because they feel comfortable that you’ll succeed in their place, and that the organization they care so much about will succeed then, too.

As an editor, publisher and critic, I get to see the work and energy being put forth by new gens, boomers and all those in between and most of it is passable, some is dismal, but happily, a good deal of it is exceptional. Understanding the arts and audiences is a far tougher job than most people realize and it takes an enormous amount of creativity and cleverness to entice those paying customers through the ticket tearers and turnstiles.

Even at 72 I know I still have a lot to learn, and have never ceased exploring new terrain, and treasuring the viewpoints of those much younger than me. Both ends of the generational spectrum bring unique perspectives to the job we do, and to dismiss any of the links is to deny the synergy that can develop between all of us.

I love to mentor, and you know what? I am still being mentored too. The worst thing to do is to think you alone have the right answers. To think that would be to think I know it all. And I don’t. I suspect that is why I have been modestly successful at marketing the arts to a wider audience.

Of course it is ludicrous to tell everyone above a certain age to retire (for one thing, these days, who has any money to retire on?) But it is equally ludicrous (and all too common) to tell young professionals that are the age you were when you were tapped for leadership that “you wouldn’t hire yourself at that age” if you had to do it over again.

I was at a Theater Bay Area conference as part of an emerging leaders group where there was a session with head hunters for executive leadership positions in the arts. The session was ostensibly on how younger workers could prepare and frame themselves for consideration in these national searches.

But one of the head hunters said point blank, “I think you are foolish to try. These boards want to hire someone who looks just like them. Someone who makes them feel comfortable. They look at you and they see a kid. Even if they were your age when they founded their own companies.” The panelists went on to say that at the top of our fields, the job market today is almost entirely laterally shuffling. Artistic Director A moves to company B, Artistic Director C moves to Company A, etc. Associate Directors are not getting promoted (and when they are, they are likely to be as old or older than the artistic director they replace.

The real issue, in my book is not that people who are in positions and are happy in them should feel any pressure at all to “move on.” I value ideas, experience, leadership, mentorship, at any age.

But when a current leader DOES move on, the decision trees around hiring a new candidate often actively exclude younger leaders from consideration.

I’ve been very fortunate- I’ve had great bosses and mentors who have created space for me to grow within the organizations I have worked in. I have yet to hit a glass ceiling because of my gender (perhaps because, as an arts marketer, I am already in a traditionally feminine field). But I have definitely had to fight for my seat at the table due to my age upon occasion.

I suppose that challenge will fade with time and grey hairs added to my head. But in the mean time, I do worry about the creative capital being lost as smart, creative younger workers are left spinning their wheels without meaningful opportunities to show what they are capable of. We don’t need more theater companies, as Rocco Landesman so pithily announced at the Arena Stage new play convening. But we are going to keep getting them, in droves, as long as young creatives keep getting the message that the only way up is out. For many young creatives, launching a theater company is the only way they can prove who they are to the world, and their only hope of ever being respected as an equal contributor to the field.

I’m days away from turning 30, and I have been generally happy with my salaries, raises, promotions, mentoring, etc. in my short NPO career. Is the money and perks less than what my friends at Google or in finance make? Yes. Are the hours longer? Not really. Have I been, more often than not, happy with manageable stress levels? Yes. But, I’ve also worked many many jobs, from warehouse to line cook, landscaper to book store clerk, and let me never forget the brief stint as grocery store meat department lackey. I know what it’s like to really be stressed, disrespected, taken advantage of and all while doing something you only kind of care about (or don’t at all). In my NPO career, I’ve certainly been tested – trusted enough to be tossed in the shark tank, sometimes I’ve made it out alright (kick them in the eyes) and sometimes I’ve gotten plenty maimed. Sometimes I’ve had help while I’m dodging hungry maneaters and treading water, and sometimes I haven’t. I’ve always learned something, even if its what I did wrong. Of course, I’ve gotten exasperated by the amount of work asked of me, but that’s why I have soccer on weekends, a garden, a guitar I will forever play poorly, a bike to tool around on, beer to make (and drink), good friends and a supportive partner. If it was all work all the time (which I find too many folks my age getting sucked into sometimes), I go as nutty in a jiffy.

To Next Gen (this is the first last time I am using this label), I have to say this:

1: Don’t expect a gold star, but do your best and take personal pride in what you accomplish.

2: Give (and take) credit when credit is due. Acknowledge the contributions of your mentors, co-workers and colleagues, but also yourself (but be humble).

3: Bitch at the bar, not at the office. And a get a life, outside of work.

4: Slow down, chill out and enjoy yourself. Your life will not end if your not listed on the Top 40 under 40.

5: You are not in this alone. Ask for help. Ask for advice.

(Sound condescending? Chill out. It’s just advice, take it or leave it.)

To Boomer, X and other managers:

1: Be embarrassed and maybe a little ashamed at what entry level NPO workers are often paid. The best advice I ever gave a co-worker who was being hired after supporting the organization as an intern, ask for more. The initial SALARY offered was literally poverty level. Just because we’re value driven doesn’t mean you can take advantage of us.

2: Be embarrassed and maybe a little ashamed at the new trend of replacing entry level positions with even more poorly paid internships and fellowships. New graduates can’t be independent, can’t mature, hell, can’t move out of their parents’ house if they don’t have health insurance and can’t pay their loans and rent and data bills.

3: Don’t ask the youngest person in the room for input only when questions of technology arise.

4: Don’t expect to be a mentor, but be open to be.

5: Humility goes a long way, as does openness to new ideas. With 41% of arts organizations running a deficit, we have to face the fact that we don’t have all the right answers and we could all all use some new ideas.

As a “next gen,” I agree with everything you’ve said for both generations. Respect and humility on both sides of the fence goes a long way.

I agree that people retire if they feel they are leaving an organization in “good hands”, but I also think people move when and if they have the amount of money needed to retire.

An unfortunate reality of working in non-profit is that while many of the leaders are ready to retire and comfortable to do so, they don’t have the means to do so: a 401k or some sort of retirement plan, appropriate and lasting health insurance benefits, a permanent home (specially in places like NY and California). I have heard some of them say “I’ll have to work till the day I die.”

This is something WE – next geners, current leaders, and retired leaders, must address. The unfair wages in the field. They (these wages) are not serving us well; they are keeping executive directors unable to retire in place which keeps organizations stagnant; they present a barrier of entry to great talent that can’t afford to take unpaid internships and low wages – talent that comes from diverse backgrounds both racially and economically; and they are forcing great talent to leave when bigger expenses or decisions like home ownership and starting a family get “in the way”.

Viable economic models, this is what the culture sector need to focus on.

Something the report made me curious about… Is there anyone in the arts who doesn’t “perceive themselves to be undervalued, undertrained, unmentored, overstressed, and underpaid”? Anyone at all?

I agree with Bea – the whole sector needs to work on viable economic models, and not just for us Next Gens.

Hi Clayton, wonderful article! I want to thank you for being so articulate about the give-and-take divide between baby boomers and the next gen workforce. I want to especially point out your gracious navigation of the “whining” – it’s something that I and my young arts-professionals network comes back to time and again.

Specifically, balancing feelings of large amounts of respect for the work that our mentors and leaders have accomplished with feelings of frustration and anger for much of the mismanagement, wasted time, and out of touch policy that happens right alongside it. While I think it IS important to praise all the work and leaders that have come before us, I do think it’s important (and not out of line) to also look at the situation we’re in realistically, and call attention to the areas of our system and economy that have perpetuated our unsustainable working conditions and ghettoization of the arts in America. So it’s always a question for us – how much of our outrage at how bad things are in the current system is due to our own naivete and lack of experience, and how much of our frustration is that we really do have innovative ideas and a more viable approach, and are not in positions where we can do anything about it.

Much of what i encounter (my own path included) is a turning away from current systems and organizations to forge alternate paths or approaches, which contributes to the “impending leadership deficit”, at least within those already-structured institutions. I am interested to see how the transition plays out. I think (much like trends following the recent bubble-burst and depression) it may only look like a “depression” or period of instability to those who are invested in more traditional institutions. To young artists and arts administrators who are forging new paths (much like the freelancers, inventors, and new business ingenues of our current era), i suspect it might be a time of enormous growth and possibility.

That being said, the trick is how to balance a respect for the work done before us, and a proper utilization of all the knowledge and resources that that generation has available with the drive, bullheadedness, and yes, naivete, ultimately necessary to forge a new era of sustainability in the arts.