Where does the meaning of a piece of work live? When does its particular resonance take shape?

When a playwright puts words down on paper and submits them to be produced, is there something already inherent in those words that form the shape of the meaning? Or is the true shape of that meaning created by a director, whose particular eye and concept elevate the words from the page to the proscenium?

This is not, it turns out, just an esoteric conversation.

As we move into an age where ownership in other arenas becomes more and more fragmentary—where re-appropriation and remixing and re-envisioning are ever more frequently being both pursued and encouraged as reinforcement that works of art continue to be relevant—the theatre world seems, in some ways, stuck in an old argument. Who owns the rights to the art seems less the point, these days, than who has the right to play around with that art.

In an article yesterday in the New York Times, opera critic Anthony Tommasini, writing about the dual Ring Cycles of the San Francisco Opera and the Metropolitan Opera, opened with this line: “Every production of an opera is a commentary on the work. But how and to what extent a director should make such commentary is the question.”

I’ve been thinking about the imprint of the director for a week or so now, and reading these two sentences sparked a clarity for me because it showed me that, in opera, much of the ground has already been ceded. Great operas are already great, to put it overly simply, and so, like Shakespeare, they can by and large stand a little (or a lot) of artifice built on top of them. They have, in a sense, become playgrounds for auteurs, and that is, I think, why big names like Julie Taymor really get a kick out of directing operas—who, honestly, can mess up The Magic Flute, with such a strong backbone provided by Mozart, no matter how many giant bear kites and Masonic symbols and outlandish costumes you throw in?

But at what point does a work become either so strong or so irrelevant that drastic re-imagination is encouraged, and a strong director’s hand empowered? Is it really at that magical moment when copyright runs out?

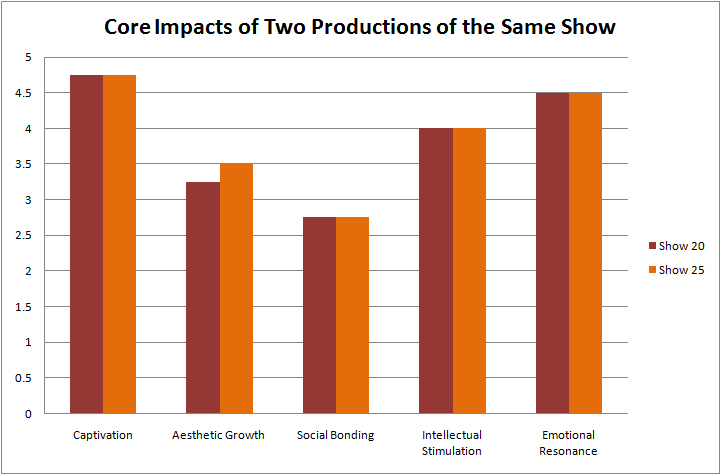

Partly I’ve been thinking about this concept—of whether there’s a heart to a good play that consistently beats, or whether it’s all built up out of the paper by those who come after the playwright (or both)—because at AFTA this year, for the first time, I presented some very rudimentary aggregated numbers from the intrinsic impact work. In the week prior to AFTA, as I was frantically pulling together numbers, one graph that I created really startled me. You see, purely by chance (okay, almost purely by chance), we have as part of the study two theatre companies doing different productions of the same play. When I graphed the aggregated impact scores for those two productions side-by-side, this is what I saw:

With the one half-step exception in aesthetic growth, the results are, as the opposing counsel in My Cousin Vinny says while standing in front of the jury and pumping his hands, “Eeeeey-dentical!” On average, audiences for these two productions of the same play, one in California and one on the East Coast, were impacted identically intellectually, socially, empathetically, and in overall captivation. Which could either be absolutely awesome or could mean nothing.

This idea of where meaning is made comes from my colleague Rebecca Ratzkin, who works at WolfBrown and is very deeply involved in this intrinsic impact research—and it’s important I note (because she would kill me if I didn’t) that drawing any real conclusions from two productions, relatively few surveys, separated by a continent, without any other comparison, is nigh on impossible. But, if not conclusions here, I guess what I see is the possibility of something that I find absolutely fascinating: what if this play really does have its own peculiar heartbeat, and neither director nor star nor venue nor time nor city can alter that particular rhythm? What if, in essence, the impacts of the play are hardwired into it?

Noam Chomsky, a linguist and anarchist (okay, political theorist) now known more for the second appellation than the first, outlined a concept in the late 1960’s that he called universal grammar. He was investigating how languages are created and acquired, and he settled on this idea that all of us, from the moment we’re born, carry in us common, innate, fundamental rules of grammar, and we use that inherent understanding to gradually build up our language comprehension and production.

I often think of art in this way—as the manifestation of something fundamental and internal, built from blocks we all carry with us even if we don’t know it. And so, in a poetic sense, it seems not out of the realm of possibility that the first step in that manifestation in the theatre would be with the words on the page. By forming the lines, the playwright in a sense locks into essence just a bit of that ineffable something that we sometimes call empathy, or sixth sense, or maybe just love or joy or common pain.

This doesn’t, however, minimize the role of the director in that world, nor that of the designers or the actors or anyone else involved—including the audience. In the terms of intrinsic impact, I would say that the contributions of the others involved increase the imprint of the impact over time. They add levels and details, nooks and crannies of complexity and surprise, that make the print of the experience that is left on people more tenacious, more ingenious, more memorable. All of which has nothing whatsoever to do with copyright.

Which brings me to Little Shop of Horrors. I’ve deliberately avoided mentioning Little Shop until now, and don’t plan to spend too much time on the particulars of what has gone on at Boxcar Theatre here in San Francisco (feel free to read along here if you want to be caught up), and here’s why: I think that the particulars of the Boxcar situation dumb down what should be a nuanced discussion about the evolving role of one artist in a socially artistic enterprise (within the context of a society that is quickly changing its opinions about what is good, and respectful, and extraordinary, and so on). The truth of the matter is that, as much as Nick Olivero wants us all to focus on the (in many ways very legitimate and enticing) arguments about the value of the aggregated, manipulated, surgically enhanced work he did with his particular production of Little Shop, at the end of the day almost everyone I’ve spoken to or read comes back to a very simple, black-and-white conclusion: Dude shouldn’t have signed a contract he wasn’t going to abide by. And I agree. And so I’d ask that this conversation be taken in the context of something larger, or at least more legal—something like, say, the amazing multimedia production of Brief Encounter that toured the world last year, and that Jason Robert Brown referenced in his insightful comments on Olivero’s letter here. That show shows what can happen within the confines of legality that still empower remixing, reimagination, reinterpretation.

In my conversation with Rebecca Ratzkin, she directed me back to Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author, a book I remember being both dense and boring that I read only small parts of in college. She noted that conversations around ownership have in some ways advanced further (or at least been going on longer) in the visual arts world and music world, and she reminded me that Barthes’ essential argument was that once a piece is completed and handed out into the world, it is the world’s, and is given over to the manipulations and interpretations of those who chose to consume it. I think that visual arts and music scholars may have grappled with this more, in a way, because in both of those cases there is a possibility that more of the original work is left behind once the initial production is completed—which is to say, there’s still a painting, there’s still a recording, there’s still the possibility of sitting down in your living room on any day, at any time, and experiencing the fullness of that work again. In theatre we don’t so much have that—because all of the stuff that turns a play from a beautiful book of dialogue into a representation of life dissipates the minute it’s done, and we’re basically left to argue over (and buy rights to) the small, valuable, absolutely essential bit that’s left at the end.

I think of it sometimes as Pandora’s box, but without the ominous music. When the box was made, it was crafted carefully, artfully, in just these dimensions and with just this clasp and lock, and it was filled with this item and that item, all humming and waiting like Jacks in the Box to spring out when it was opened. And then it was opened, and they did, and it was extraordinary, and then someone put them all back, and they waited for the next time. Every time, the same pieces, placed back differently by different hands, arranged with care, but a different specific care, each time. The core remains, but it’s nothing without the hands that present it to the world.

Thanks for this insight, Clay.

“Art is never finished, only abandoned.”

-Leonardo da Vinci

Clay, this is beautifully stated. Thank you. You’re absolutely right that the important debate has been lost in the Boxcar situation—do copy rights need to be shorter? should there be extra licensing options for those who wish to create adaptations? and how can we as the creative class have a dialogue through our art, when much of the point of art is to dismantle or reconfigure what came before? Many creative people wish specifically to use an existing work as a basis for a newer work, or have the opportunity to present it in a new light in order to continue a conversation about that piece or about the place it holds in our collective consciousness, because of their intrinsic value. Often unusual casting or mash-ups really do help us appreciate the overproduced piece afresh, so these types of “adaptations” really ought to be encouraged somehow, while still making sure the originators get proper credit and royalties, as is completely uncontroversial with covers of pieces of music. When I was running my all-female company, I rarely knew what to do when approaching rights holders: when contacting the writer directly, I always made sure they knew we were an all-female company and that therefore all roles would be played by women; with big agencies, I did not, because I felt we would not get a fair hearing. In the latter cases, I did not hide our distaff nature, but I also didn’t mention it, leaving it to them to research us if they chose, as any internet search of our company name would give them that information instantly. It was interesting to me that with my all-female production of Brecht/Weill’s “Happy End” the Weill Foundation objected to us having a three-member band (so we cut it back to one) but not to women playing the roles. And for those who don’t understand why producers are so quick to sign licensing agreements they are fairly sure they won’t honor in entirety, please know that the licensors are a big part of the problem too: early in my career, a licensing agent quizzed me about how I was going to produce a certain show, what the costumes would look like, what music I would use with the piece and so on. I finally just had to say that I would be presenting the entire text in order with no changes, that, beyond that, there needed to be room for my vision, and that if they wanted complete artistic control over the piece, they needed to produce and direct it themselves. At that point I asked them whether they wanted my money or not. The translator and friend of the author came to check out the production and apparently liked it just fine, though he asked why I had been so literal with the script. (!)

It’s a sticky question as to how far a director of a play can go in ‘altering’ what’s on the published page. Naively I might say that ‘it’s between the director and the playwright’ coming to terms with minor/major changes to a script. But when the playwright’s not available, then what?

A dramatic work, read in much the same manner as an essay, a short story or a novel, is one thing but to breathe life into it as a living theatrical production is another, and the terms of copyright infringement should apply differently and permit some leeway to the director in pursuit of his artistic vision for the piece.

Should a director be expected to duplicate bit by bit the exact original production? I say no. Where is the creativity in that? A director, to some degree, should have the freedom to interpret the play as he sees fit. However, directors should be held accountable for making extreme changes that alter or deviate from the writer’s original intent.

I would argue that unless the playwright wishes to direct every production of his/her play or musical he/she must understand that by putting the work ‘out there’ into an artistic arena and into the hands of a director, and actors as well, this then becomes, if you will, a collaboration of sorts and that by doing so he/she, whether present or not, must be willing to accept that some new ideas, concept, or vision might emerge regarding the work, something which was not necessarily in the writer’s mind in the first place. One might cite the productions of COMPANY and SWEENEY TODD ‘re-invented’ by director by John Doyle as examples of works that deviated somewhat from the original. Had Sondheim ever thought of putting the orchestra on stage with the instruments in the hands of the actors? This is not to say that I condone, without valid reason, changing words, pages of dialogue or the names of characters or even the inherent structure of the work. I must admit that in several productions of Shakespeare I have reorganized several scenes in order to make for a better flow.

A number of years ago in Los Angeles I was to direct a production of two one-act plays by James McLure jointly titled “1959 Pink Thunderbird” (“Lone Star” and “Laundry and Bourbon”). Initially the rights were given but since this was to be a professional production McLure felt he needed to be present during rehearsals. Unfortunately he couldn’t and the rights were withdrawn.

In my experience a clean script, free of all blocking and other assorted comments for the director or actor, should be available (or it can be retyped); otherwise. the first thing I will do is to instruct a cast to mark out most of the blocking, and in some cases, emotional suggestions (e.g. ‘said with great sadness’) included in their scripts. I feel this, for the most part (unless it is totally essential to the action of the piece such as entrances and exits or actions e.g. John takes a large kitchen knife and kills Sally), not only hinders the actors in the development of their character but, in general, the working process of getting the play on its feet. Does this, in itself, violate the agreement with the licensing agency such as MTI or Samuel French? I make this decision for several reasons: 1) I suspect that most of the blocking that exists in a published script was not so much put there by the playwright but, in most cases, by the stage manager to document the original director’s work whose vision as to how the actors should move about the stage may not necessarily coincide with mine and 2) that once the actors begin to make the roles their own, they may want to move about the stage differently than what is suggested. Should I be penalized for copyright violation?

Tennessee Williams goes to great lengths to annotate his scripts. How closely need these comments be followed? He was also notorious for attending productions of his plays when one was within traveling distance and having them closed down because he did not approve of one thing or another.

For Beckett to object to an all female cast, even when the entire point of the play is retained is a bit ludicrous. How do you present a production of “Waiting For Godot” at an all girls school? This also begs this question … for me anyway: Though I would not entertain this concept, I wonder, were August Wilson alive today, would he have sanctioned an all white cast for one of his plays? (Has it been done?)

Should a licensing company that handles a play where the word ‘nigger’ is infrequently used disallow any production by, say, a high school group, who want to honor the importance of the piece while at the same time feel, out of necessity, that that word should be cut?

All in all I think each work, to the extent of how much change it can take on before it becomes too distorted, must be dealt with individually and with discretion by the director.

A director who wishes to ‘put his mark on the world’ by doing something ‘revolutionary’ with an existing dramatic work, particularly one that is not in the public domain, might do better to rethink his/her reasoning behind such a decision and perhaps set out to create something original and not try to improve on something that is already proven to be successful as written.

(also posted on the Theatre Bay Face Book page.)

Seriously, your quandary is how to do ‘Waiting for Godot’ in an all girls school? By having the girls play men. The same way that you do any play that is supposed to be done in an educational environment. By having the students that are available dress up and act as someone else. What if you’re in an all Asian school and you need someone to play a white guy? Make up and wardrobe, or a script change?

If you don’t like what a writer has written, don’t do the play. Write your own. To take a writer’s work and perform it other than how he wrote it, you are putting words in his mouth. Not his words, It’s a lie, is what it is.

If you haven’t the balls to name a character ‘Nigger Jim’, then you haven’t the balls to produce anything with Huck Finn in it. If you haven’t built an audience and educated them in the ways of theatre, maybe you’re not ready yet if they’re not ready yet.

Writing is an art form. Directing is an occupation. I am a sound engineer, and I would no sooner change a playwright’s words than I would mute a singer’s mic and replace it with a recorded track of someone else. It’s the same deception in my eyes.