I was recently at a party (not drinking because I’m on this tragic cough medicine that promises a face rash if I mix it with booze – or maybe the doctor lied about that when I seemed vain?) and an artist was complaining that his album only sold 400 units (digital and physical) in its first week, all the while getting 6500 complete Spotify plays. This artist lucked out on account of the cough medicine, because I didn’t go into my usual rant on the subject. The transaction is: artist signs with a record label, label is in charge of how an album is heard, artist gets paid to make a record no matter how many units it sells, artist does not get to decide the value of a listen on any given platform.

We need to get away from the idea that any one method of consumption has more value than another, and rather, focus our efforts on converting encounters with music into true fandom.

I realize that a consumer buying the album directly from the artist literally does have more monetary value to that artist. No one, though, would argue that having a clip of track on a TV show, for example, doesn’t have value, even though no one consumer is paying the artist directly for that. If I’m watching The Vampire Diaries (which believe me, I am), I’ve paid Apple for hardware, Verizon for internet, and Hulu Plus for content. I’m watching the commercials from the advertisers that are also paying Hulu. Hulu is paying The CW, who is paying…the vampires!…the actors, creatives, and production team. The CW is also paying the music supervisor who selected the song and the legal department that negotiated the terms for the music that I’m now hearing on the show that I may or may not buy, but that I am now aware of, with context. Having a song on a TV show or on a movie soundtrack would never be considered giving a song away for “free,” because it raises the artist’s profile, and logic dictates that the opportunity will make the artist more money, eventually.

I’ve long admired Martha Stewart for her, or her team’s, ability to cross-promote all aspects of her being. In her print magazine, she directs readers to her Twitter feed. On her Twitter feed, she directs people to her Sirius XM show. On her Sirius XM show, she directs people to her blog. In the magazine, she advertises her line for Target. Through her Target line, her products live in your home, which makes you want to follow her on Twitter, read her magazine, listen to her on Sirius XM, or watch her AOL, Hulu or YouTube videos. Round and round on the Martha wheel we go, and we don’t even remember where or when we go on: did I even buy a ticket for this ride? I have a particularly fond memory of her American Express commercial, where she re-tiles her pool with the other credit cards she had cut. An “exclusive [Martha Stewart] partnership with Triscuit” for the “launch of the Triscuit Summer Snackoff” was just announced.

Is the aim to get an official summer snackoff partnership? (Maybe? Snacks!) No, but the aim is to connect the pockets of an artist’s influence in a way that makes consumers, bodies, aware of all an artist’s activities. You’ve listened on Spotify for free or as part of your subscription: did you like the music? You did? Great. Did you tell your friends to listen to? You did? And your social media followers? Terrific. Is there a tour? Oh, the artist is coming to your town in a month. Did the friends you told about the artist like it, too? Maybe you should all go to the concert together. Oh look: there’s merchandise at this concert. Maybe you now want a physical CD because you’re chatting with the artist, he/she signed it, and it’s suddenly something for the bookshelf. Someone comes over for dinner: what’s this signed CD on the shelf? It’s this great artist so-and-so we went to the concert last week, you’d like him/her.

There: the artist got the direct sale after all, it just took a lot more than a Facebook ad.

My favorite review of all time, for selfish reasons, is a 2011 New York Times review of Hilary Hahn’s concert at The Stone. In it, Steve Smith writes, “Thus, instead of a conventional affair at Carnegie Hall, or even a chic night at Le Poisson Rouge, Ms. Hahn gathered her flock into a cramped brick space on an unseasonably warm evening.” It’s “flock” I like, not only because of a light obsession with collective nouns for animals, but because that’s what every artist should want, as far as I’m concerned: a flock that goes with them, and a flock that grows.

I first heard of John and Hank Green (“VlogBrothers“) and their valiant Nerdfighters through Jonathan Biss and his brother. Suddenly, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars is another “YA” novel I haven’t read and now a movie and my sister being all “how do you not know what this is stop watching Star Trek and live in the world.” Seven years of free content via VlogBrothers, and now The Fault in Our Stars makes more money than the new Tom Cruise movie.

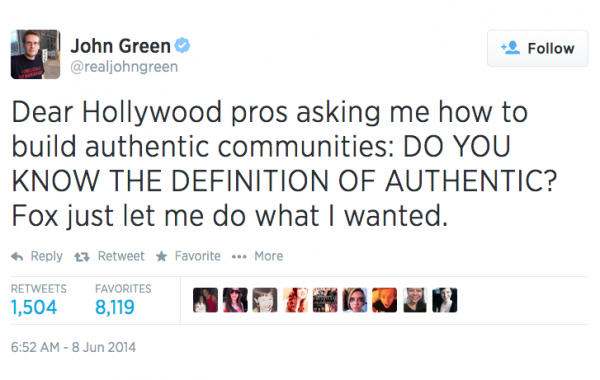

It seems Green has gotten a lot of press and industry questions about building “authentic” fan communities. One wonders, “If you have to ask…”

I especially liked this Tweet:

So tend to your flock, don’t fuss about whether or not they paid at the door.