Last week, Anthony Tommasini of The New York Times wrote a feature about CD box sets. In it, there’s a fascinating quote from Nonesuch president Robert Hurwitz about Nonesuch’s recently released Elliot Carter collection:

Mr. Hurwitz expects this set to sell satisfactorily, he said. But if it

does not, so be it. “We have had a lot of longstanding relationships

with important composers and performers over the years,” he added. “At

different times it seems to me to make sense to put together recordings

without thinking about a target audience.”

Releasing recordings (or producing a concerts) “without thinking about a target audience” is at once noble, pure and completely idiotic. Both sides could be – and have been – convincingly argued; where is the give-the-people-what-they-want line, and when does artistic integrity suffer? If the audience (or potential audience) is ignored, are recordings/box sets/concerts simply vanity projects? If the sales numbers are paid too much attention, is creativity dead?

The idea of a “target” audience in this quote is also noteworthy. Do we get so caught up financially and mentally attempting to reach the target audience that we ignore anyone not within the confines of that pre-established target? That is, once an audience is identified, who then gets ignored? I often find that in our attempts to reach “new audiences”, we forget about the audiences that already exist; the consumers who would buy an album if only it was brought to their attention, no salesmanship or clever marketing tricks required. We spend so much time trying to connect with non-traditional audiences that the X percent of the population (3%? 5%?) that already cares about the performing arts is overlooked. 5% of the US population is…still a lot of people.

This reminds me of an excellent post by playwright Jason Grote on an ArtsJournal group blog I worked on for the National Performing Arts Convention (NPAC) last June. His essay corresponded to an NPAC session called “Stop Taking Attendance and Start Measuring the Intrinsic Impact of Your Programs”, and was about audience surveys. The entire post can be found here, and below is an excerpt:

I generally think that surveys measuring audience response are a bad

idea. I care very deeply about what my audience thinks or feels, but I

don’t feel that surveys are the best way to assess this, and so don’t

use them. If the theater wants them, I consent, but I don’t read

them. This is not because I am a snob who is disinterested in what my

audience thinks – on the contrary, I care very much – but because I

think our contemporary culture has a weird fetish for quantifying

everything, and something so delicate and ineffable as the relationship

between artist and viewer can’t even really be expressed verbally, let

alone numerically. I am, in many cases, a believer in the wisdom of

crowds and a fan of most open-source projects, but theater isn’t

computer programming or the collective hive-mind of Wikipedia. I find

it much more instructive, actually, to watch an audience watch my work

(as was easy to do at the Denver Center’s in-the-round Space Theater in

2007), a technique recommended by the filmmaker Francois Truffaut,

among others. Collectively, an audience is very intelligent, but not

necessarily in a way that individual members can articulate – often I

can better tell whether or not a play is working by observing body

language. When are people laughing, crying, shifting, on the edge of

their seats, dozing off, walking out?…The best art polarizes as much as it unites. Most art that seeks to

please everyone is doomed to failure, mediocrity or, at best, a sort of

temporary popularity. This is not to say that genre art can never be

good – I’m a fan of The Wire, Philip K. Dick, sketch comedy, comic books and pop music as much as I am of, say, Lawrence Shainberg’s novel Crust,

the poetry of John Ashbery, opera, or performance art, and often the

two categories are not mutually exclusive (note the references to Flann

O’Brien’s The Third Policeman on the TV show Lost, an

incident that caused the postmodern novel to sell more in the last year

or so than it did in the entire 20th Century). What I object to is the

attempt to domesticate and commodify a process that tends to sour at

its very contact with such concepts.

I am interested to hear from marketing departments at both record labels and arts presenters on this subject. How often do your A&R people or artistic administrators ask your opinion before releasing a record or booking a performance? Is it a discussion, or are projects simply handed to you to market from above? Even if there is discussion, are your marketing opinions taken into consideration or largely ignored?

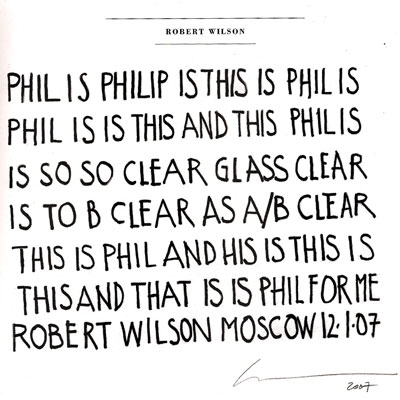

As a side note, I have to respectfully disagree with Anthony Tommasini about the Nonesuch Philip Glass box set (“a six-inch-square box, an oversize thing adorned with glossy photos and too bulky for a standard CD shelf.”), also highlighted in the Times box set article. I, for one, think it’s just the coolest thing: I especially love the five fine art interpretations of Glass circling the box and the book(let) that includes “appreciations” by people such as David Bowie, Chuck Close (obviously), Martin Scorsese and Robert Wilson, whose appreciation I have scanned:

I’m also glad no one was around when I first opened the box, because I squealed like a little girl who had just been given a pony when I saw that the inside panel design matched Glass’ website:

I’m also glad no one was around when I first opened the box, because I squealed like a little girl who had just been given a pony when I saw that the inside panel design matched Glass’ website:

Of course, I’m the target audience. And my only hope is that all the labels don’t go under before Nonesuch gets around to releasing a “We Do Not Belong Together” Sondheim box.

Of course, I’m the target audience. And my only hope is that all the labels don’t go under before Nonesuch gets around to releasing a “We Do Not Belong Together” Sondheim box.

At the venue I work at, we’re absolutely never asked whether or not a performer will sell tickets. And then, of course, we’re yelled at by our programming director when performers are not selling tickets. Round and round on the ferris wheel we go…

We’re never asked, either, and like “Joe” says, we’re still held accountable. Mr. Hurwitz’s quote is ridiculous, as you point out, because as long as he still receives a salary, he’s focused on making money. Which means he’s focused on selling albums, which means he cares about the audience.

Great job on the blog, btw! My whole department reads it daily.