It’s no surprise that Mario Testino’s photographs, some of the most iconic of which are currently on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, are  attracting thundering hordes.

The images, which I ogled yesterday on my first ever visit to the MFA, are huge, colorful, sexy and packed with celebrities and super models from Madonna to Kate Moss.

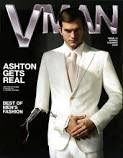

But besides Testino’s brilliantly disconcerting image of the actor Ashton Kutcher looking Photoshop perfect in a pristine white suit with an arm savagely torn at the elbow to reveal the wires and cables of a robot, I was completely bored by the eye candy on display. It amounts to little more than celebrity porn, even if the colors are rich, the prints, glossy, and the torsos depicted, beautiful.

Of much greater interest is the museum’s current The Postcard Age exhibition. The show brings together around 400 postcards from the collection of Leonard A. Lauder. What’s fascinating in our age of Twitter, Facebook and email is how powerful the postcard was a hundred years ago not only as a medium of communication, but also as a means of transmitting political, social and commercial messages. Plus, many of the tiny canvases on display are gorgeous works of art.

I was particularly struck by a pair of postcards depicting photographs of men’s neckties on which scantily-clad ladies clung to the central knots. Cards like these apparently inspired the surrealist art movement. A card with a painting of a fat man running down a beach with arms outstretched above the tagline “Skegness is so bracing” made me laugh: Â Anyone who grew up in the UK would find this reference to the windswept and barren resort town of “Skeggy” to be funny.

The exhibition is packed with small wonders that reveal a world of rich communications that seem so much more tactile and personal than the mediums that proliferate today.

Oh, and I should mention how much I enjoyed wondering around parts of the MFA’s permanent collection too. The museum has clearly thought a lot about how to activate spaces that might attract less people than big-draw exhibitions such as the Testino photography show.

In one of the more gaudy nineteenth century American art galleries packed with white marble sculptures, it was fascinating to chat with a young man who was demonstrating and answering questions about how sculptors work with stone. He was seated in the middle of the room at a table with a plaster cast bust and a stone bust as well as a bunch of artist’s tools. The presence of the docent in this capacity makes people slow down and pay attention to the work in a gallery that might otherwise be more of a “walk-through” space.