Since the media industry is what optimists call “going through a period of transition” and pessimists call “in the shitter,” arts journalists have increasingly found themselves losing their jobs, and, whether on staff or freelance, working harder for less money. Nothing about this is new and it seems unlikely as far as I can tell, that things will change much for the next five to ten years.

Since the media industry is what optimists call “going through a period of transition” and pessimists call “in the shitter,” arts journalists have increasingly found themselves losing their jobs, and, whether on staff or freelance, working harder for less money. Nothing about this is new and it seems unlikely as far as I can tell, that things will change much for the next five to ten years.

But what I’ve come to realize lately is that under these circumstances, arts journalists are starting to look more and more like artists in terms of the piecemeal way that they are scratching out their existences in order to practice their craft. Like the actor who waits tables for a living or the folk singer who temps in a law office to make ends meet, these days, journos are having to hold down all manner of part- and full-time jobs that have nothing to do with the media in order to continue doing what until a few years ago would have been regarded as a profession. Now, arts journalism is for many a vocational sideline.

With the non-profit model becoming increasingly common among news organizations, the arts-journalist-as-artist concept is similarly taking shape. But the tricky part of this is that while there are lots of mechanisms in place to support the work of artists through residencies and grant-making programs, society hasn’t caught up yet with the notion that the people who cover the arts also need this kind of support these days to practice their craft. There are a few isolated financial opportunities for arts journalists out there such as the very enlightened Warhol Foundation funding for members of the visual arts media. (If you cover music, dance or other artforms, the Warhol Foundation can’t help you, though.)

But in general, arts journalists are slipping through the funding cracks: Arts funders typically don’t fund arts journalism; they want to support artists exclusively. And media-oriented foundations and fellowship programs seem to be far more interested in supporting areas like investigative, education, science and political journalism as well as media entities that serve underprivileged communities than getting behind arts journalists.

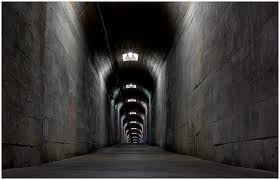

It is the nature of the world that some professions are no longer useful to society and therefore become extinct. For example, pianists used to make a good living as employees of cinemas, playing for silent films, but this job barely exists today. It’s going to take a lot of educating to make people see that quality journalism – and quality arts journalism in particular – still have value in today’s world. But there’s no guarantee that this will happen. If the funding mechanisms necessary for supporting the profession don’t develop soonish, it won’t be long before arts coverage is solely practiced by moonlighting waiters and nighttime corporate security guards. But unlike their colleagues in the novel writing, standup comedy and singer-songwriter worlds, it’s unlikely, at least in the present situation, that these hobbyist arts junkies will have even the small light of grants, fellowships, residencies and other forms of patronage to sustain them through the dark hours.