In recent years an artist named Carter Gillies has written to me with some regularity in response to Jumper posts. I have always valued his letters, which are invariably insightful, provocative, warm, and encouraging. Recently, Carter dropped me a line and mentioned that he had come across a Facebook post by Clay Lord soliciting a better framing of the intrinsic/instrumental distinction.

In recent years an artist named Carter Gillies has written to me with some regularity in response to Jumper posts. I have always valued his letters, which are invariably insightful, provocative, warm, and encouraging. Recently, Carter dropped me a line and mentioned that he had come across a Facebook post by Clay Lord soliciting a better framing of the intrinsic/instrumental distinction.

Carter then shared that he had been rather astonished by the manner in which the word ‘intrinsic’ was being used by arts types posting comments as it was quite different from the ways that philosophers and psychologists have tended to use it. He wrote, “It was as if an entirely new word had replaced the one I was familiar with.”

He elaborated.

Inspired by his letter, I suggested that if he hadn’t already done so he should write a reflection on the topic and I said that if he did so I’d love to post it on Jumper. He agreed. I won’t preface what Carter has written beyond saying that I believe it is truly worthwhile for those occupied with understanding and articulating the value of the arts as it seems that there is something fundamental to this endeavor that many of us have either forgotten or abandoned for political expediency.

(BTW, if you are so occupied you may also want to check out the recently published report, Understanding the Value of Arts and Culture.)

Carter has a blog of his own, which you can check out here. I asked Carter for a bio that I could share to introduce him along with his post. Here’s what he sent me:

At some point during philosophy graduate studies Carter found himself with a lump of clay and a potters wheel and immediately knew he was intended for a life in the arts. It also turns out that the things most worth thinking clearly about are the ones we care about, and so he spends his days making pots and asking questions about the nature of art, beauty, and their place in the world.

This is a long post; but, hey, Jumper readers are used to that. 😉

So grab a coffee and enjoy!

I sometimes look at the arts landscape and feel we have gotten our wires crossed. Its not always easy to define, but for me, at least, there is a pervading sense we are making correctable mistakes.

Difficult questions can often be solved by either moving up or down a level. The problem, it sometimes turns out, is in the manner we are addressing things. We find a new framework for measuring or by setting different parameters. Sometimes, also, it can be in a refining of our terms, scrapping some and replacing others. Sometimes its knowing the right questions to ask. Even a tentative answer to a good question is better than a great answer to a bad question. It just feels as though in the arts we are occasionally asking the wrong questions.

An apparent issue facing us is how we understand values. I’m not just talking about our own values as opposed to other people’s, but the role and function of values and where values actually fit in a person’s life. We often seem to talk about values without knowing what they are there for.

One problem I ran across recently was our use of the word ‘intrinsic’. This term has a long and storied history in the fields of philosophy and psychology, and yet when used in the arts we are often left dissatisfied.

I have seen too many references to ‘intrinsic benefits’ and ‘intrinsic impact’ not to be aware of at least one wrong turn we have taken. The distinction we use this term for in the arts is, in this instance, the difference between things that are good for us personally and wider social benefits. We take ‘intrinsic impact’ to refer to our own individual benefits, and ‘instrumental/extrinsic’ to refer to external social goods and the like.

The problem is that ‘benefit’ and ‘impact’ are already the language of instrumentality. They denote an effect, what something can be good for, the means to ends, utility, and this is precisely what is meant by instrumental. When we use the word this way we are not making a contrast with instrumentality as much as we are defining the way in which a thing is instrumental.

The way this term gets used in philosophy and psychology is to make plain the difference between things that are justified by something outside themselves and things that are justified in themselves. It is specifically the difference between means and ends. A means is whatever thing benefits or impacts some other thing. The value is derived from being a means. It serves some other end. The end is not valuable in that way. It is that from which the means takes its value. It represents the value itself.

Think of it like this: We are measuring something and we wonder what measurement is justified. We take out a tape measure, hold it in place, and see that this here thing is two feet four inches. The operation of measuring has been successfully carried out.

But what exactly have we done? This is an important question. There are things in the world that we measure, and this becomes an empirical issue, but there is also the measure itself, the thing from which we derive measurements. That thing exists in the world too, but the role it has is different. It’s not thing being measured but that which does the measuring.

‘Two feet four inches’ is how something else measures up, is justified, by our use of the measure. We question how things will be measured, but we do not have the same uncertainty about the measure itself. That stands in a different relation to what we do. It is the ground we assume when we evaluate things in the world. It’s not a question, even an empirical question, but a definition. It’s the standard itself. It is the logic that connects things.

That may take some time to process, but it absolutely relates to the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic values. And this is crucial for us.

Consider: The world is full of things with instrumental/extrinsic value to us. There are plenty of means to our ends. But where does the value of our ends come from? If a means is valuable because it serves that end, where does the value of ends come from?

Ends function for us in much the same way as our yardsticks and tape measures do: The ends are that which measures the value of means. They are a logical aspect of the way we confront the world rather than an empirical question to be decided. Ends function for us by being accepted as intrinsic values, as things not needing to be justified. They are part of the definition. This is simply how we value the world. We deem these things worth holding onto. Its the scaffolding we hold in place to make sense of things.

And it turns out there are many such values. We put them in our important documents. “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness†are not things we look to justify in some other way: They are the grounds upon which our actions are measured. Not every value is a means, and most others come to a place that requires no further justification: This is simply what we do. It describes a way of acting, a culture.

When we determine that something is beneficial for something else we have solved an empirical connection: “Yes, the arts are good for the economy!â€. What we have not done, the thing we don’t always question, is what form of value the economy takes. The relationship we have proposed is that the arts are a means, and we are using the economy and its like to justify the arts.

But if we are saying the arts are important “because of their benefit to the economy†are we really saying that’s why the arts are important?

I don’t want to suggest that the arts are not worthy in this role, as the servant to other established goods. I simply question whether the arts are only that. We have given the arts as a means, but can we claim them also as an end? The role of servant is respectworthy, undoubtedly, but I know few in the arts who value the arts merely as the means to some further end. Additionally, perhaps yes, but not only on those terms.

There is a confusion here, and I’m not sure it is only by omission.

For most people in the arts the value of the arts does not need to be explained. The arts themselves are a measure of value. The arts are worthy in their own right. The arts have intrinsic value. They do not need to be justified.

But then, how is it we spend so much time talking about the instrumentality of the arts? Well, because not everyone gets it. Not every person values the arts as a centerpiece of how they think and behave in the world.

For many people the arts are not only incomprehensible but are entirely without value. So when we talk to these people we are talking to folks who do not yet have a meaningful role for the arts. It holds no significant place in how they look at the world. Its not a part of their scaffolding. It’s handing them a tape measure when they have no cultural practice of needing things measured.

How do we talk to them, even? How do we get them to see value in the arts? We know it as part of the foundation of our own values. How can we communicate that to others?

This is where advocacy steps in. And unfortunately these core values are not transferable in an immediate sense, like putting on a new coat. We are discussing the foundation of a person’s world view, so its not as simple as getting them to switch between metric and the US version. Its not a difference between two standards that do exactly the same thing. Its not just a matter of translating from one set of units to another. Rather, it’s the whole idea of measuring itself. And there is no simple translation for that. Core values are an integral part of who people are.

So how do we talk to people who are fundamentally different from us? Well, our intrinsic values are hidden from them, and theirs from us, but there are empirical connections between things in the world. And the arts have done a good job identifying where some of the overlap may exist.

The way we mostly talk to these people is we have found that our ends, the things we value in themselves, can be the means to their own ends. They value the economy? Well, the arts are good for the economy! They think that cognitive development is important? Well, the arts are good for cognitive development! We make our own ends the means to their ends.

But this never teaches them why we value the arts. It is not a conversation that discusses the arts the way we feel about them. Its not a picture of the intrinsic value of the arts, because in talking about instrumentality we always make the arts subservient. That’s never only what they are to us. Sometimes we just have to make the case for a lesser value as the expedient means to secure funding or policy decisions. It’s better than not making any sense at all.

The question, then, is whether discussing the arts this way is a path to truly persuading folks to our point of view, to appreciating the arts in themselves.

Why is this an important question? Well, we are trying to convert folks to our cause, that the arts are not extravagant, and it’s a legitimate question whether this can be done by the rational instrumental means we are offering.

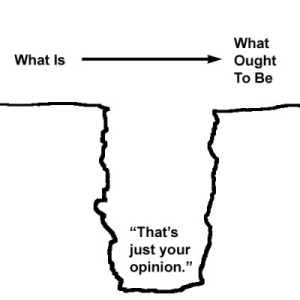

At some point in the 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume rather conclusively argued that it cannot. You cannot simply derive an ought (intrinsic value) from what is (facts). You don’t become aware of the intrinsic value of the arts by pointing to the benefits they have. Things that measure value (oughts) have a different role from the things that are measured (what is). One is the foundation, the other what gets built from it. One is the definition, the other how that definition applies. Its a categorical distinction. And persuasion stumbles over even the best placed facts.

In crafting the Ripple Effect report the folks at ArtsWave came to approximately this conclusion. As Margy Waller stated in a great guest post on Createquity, don’t try to change minds, change perspective:

Instead of reviving an old debate, we sought a new way to start the conversation – based on something we can all be for, instead of something we’re defending against an attack. And importantly, we aren’t trying to change people’s minds, but present the arts in a way that changes perspective……

Members of the public typically have positive feelings toward the arts, some quite strong. But how they think about the arts is shaped by a number of common default patterns that ultimately obscure a sense of shared responsibility in this area.

In other words, the arts may make folks feel good, but they are not thereby recognized as a good in themselves. The common default patterns are simply the mental habits that devalue the arts or cast them as at best merely means to other ends. Defending the arts with facts about the arts is not actually going to change people’s minds. Rather, what is needed is a new perspective in which the value of the arts are already seen as vital.

Arts Midwest published a report last year that also acknowledged the issue:

The public will building model posits that long-term change is accomplished by connecting an issue with the deeply held values of the audiences and stakeholders a movement seeks to engage. The theory is rooted in the understanding that people generally make decisions about what to think and do based on their core values and their assumptions about how the world works. They accept facts and data that support their existing worldview and values, and they tend to reject facts and data that stand in contradiction. To create—and sustain—public will for any issue, a movement needs to find the optimal values alignment that connects their audiences to the issue.

A few years ago there was an article in Mother Jones that explained “the science of why we don’t believe science.” The whole article is brilliant and insightful and well worth a read. The conclusion is this:

You can follow the logic to its conclusion: Conservatives are more likely to embrace climate science if it comes to them via a business or religious leader, who can set the issue in the context of different values than those from which environmentalists or scientists often argue. Doing so is, effectively, to signal a détente in what Kahan has called a “culture war of fact.” In other words, paradoxically, you don’t lead with the facts in order to convince. You lead with the values—so as to give the facts a fighting chance.

It is simply the case that the arts have been preoccupied in leading with the facts. As the ArtsWave and Arts Midwest reports demonstrate this is a gambit that plays for very low stakes. Its not a strategy that even remotely stands a chance of scoring on the level of fundamental values. Facts are disputable, despite the conviction with which we ourselves hold onto them. We find certain things obvious, and the reason we do is that the facts we hold dear always reflect our values. We ignore facts that don’t line up or contradict our core intrinsic values. Blame the human temptation for motivated reasoning. Instrumentality only gets us so far. It’s not the measure of value itself, but a fact aligning with some other value.

Studies the arts have conducted have barely begun describing the surface phenomena, and this is not yet an explanation. Yes the patient is sick, but we do not know the disease. We are confused about intrinsic and instrumental values so we blur the lines and fail to distinguish their radical difference. This is a category mistake, and not knowing this difference has too often blinded us.

I have heard it expressed that data and arguments in favor of the arts are like arrows we cast at the problems facing us: We hope some will stick. When the arrows fail we assume we just need better arrows, more armor piercing facts. The problem, unfortunately, isn’t the arrows but mistaking the target for a thing that can be reached in this way…..

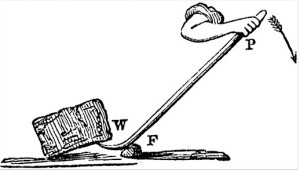

Perhaps this is a better way of looking at it: In the third century BCE Archimedes said, “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it and I shall move the world.†Facts are like levers, but they do not function to move things unless resting on a congenial foundation.

In the arts we have thrown facts together, constructing the longest possible lever, but have seemingly forgotten we also need somewhere to place it. Those facts need to rest on values that can act as a fulcrum. The facts without value, or the wrong value, will simply have no leverage. They will fail to motivate. Something needs to hold fast. A lever hung on a speck of dust won’t work. Facts without a decent fulcrum are not even a lever, just a wobbly stick…..

The arts have mustered plenty of cogent facts as to why the arts are amazing, and yet we spend too much time scratching our heads wondering why our efforts fall on deaf ears. What’s at stake for us is not facts about the arts but the value of the arts. The sooner we embrace this the sooner we avoid playing losing games and spinning our wheels without significant traction.

To turn the tables on what Margy suggested, perhaps it is WE who need a change in perspective. The confusion we are mired in is thinking that our difficulty is practical when in fact the impediment is structural. We need to better understand this to make appreciable headway. We can celebrate both the good art does and the good art is, a structural difference, the lever and the fulcrum. That is the value of intrinsic value for the arts.

***

Archimedes’ Lever: Engraving from Mechanic’s Magazine (cover of bound Volume II, Knight & Lacey, London, 1824). Courtesy of the Annenberg Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AArchimedes_lever.png

Tape Measure Photo Attribution:Â By Pink Sherbet Photography from USA [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

David Humes Is-Ought Attribution: From the Website John Ponders:Â https://johnponders.com/2012/11/15/humes-guillotine/

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

![By Pink Sherbet Photography from USA [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Common](http://www.artsjournal.com/jumper/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Free_coiled_tape_measure_healthy_living_stock_photo_Creative_Commons_3209939998-200x300.jpg)