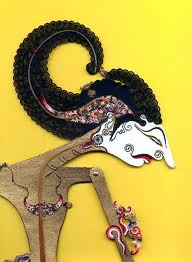

A followup: the Asia Society posted the  entire video of the  3.5 hour wayang kulit (shadow puppet and Javanese gamelan orchestra  performance) that I wrote about Sunday — the one in which President Obama stopped by — in five parts. And colleague Richard Gehr wrote up the event for the Village Voice blog.

performance) that I wrote about Sunday — the one in which President Obama stopped by — in five parts. And colleague Richard Gehr wrote up the event for the Village Voice blog.

Obama at Javanese shadow puppet show, Asia Society

President Obama made a surprise cameo appearance at the Asia Society’s production of a Javanese shadow puppet show  — a Wayang Kulit — by dhalang Ki Purbo Asmoro with Gamelan Kusuma Laras on Manhattan’s upper east side on Friday night (March 16).

As a translucent strip of water buffalo hide, upright if not as nimble on his tusk-bone rods as flesh-and-blood Obama is on the campaign trail,  the puppet Obama popped up among a trio of clownish Javanese street-types. At first they addressed him with awe, one bowing to kiss the President’s ring. But then he turned assertive, urging — admonishing! — President O to spend US money on arts and education, not on war.

The puppet president said he would. Gongs struck and bells rang, a deep bass drum thumped, women sang in the highest range of human pitch, a haze of whistles, wavery flutes, bowed strings sounds or maybe just overtones arose over the gaggle of musicians sitting crosslegged at bottoms-up brass kettles lodged firmly in low, carved wood frames. The musicians hammered short, repeating note patterns on the xylophone-like metal slats, banged on slender barrel drums and struck cymbals.

The audience would have become raucous if we’d been at one of Java’s traditional seven-hour wayang kulit extravaganzas, outdoors family overnight picnics held in fields, fairgrounds, village squares, parks, schools, really anywhere. But then we’d have been sitting on the far side of a screen to watch the puppets’ shadows, rather than in theater seats at the elegant Asia Society edifice on Park Avenue. We wouldn’t have watched the shadow-side of the show on a big tv screen at the lip of the  stage.

No simultaneous English translation would have been projected above the puppet stage of the dhalang’s multi-voiced characterizations depicting Bima’s Spiritual Enlightenment and quest-search from forest floor to the ocean depths. There’d have been no live webcast of the event (I assume it will be archived eventually at AsiaSociety.org/live). We’d have been in Java or Bali.

Indonesian wayang kulits and performances by gamelan orchestras aren’t frequent in NYC, and though this one was spectacular, it required a stretch of the imagination and suspension of residents’ inherent impatience to enjoy. Obama showing up during a comic interlude spelling relief from the Bima plot lent the evening its liveliest moments.

A dhalang, the puppet master, is supposed to be adept at improvising such bits of social commentary as well as philosophical speculation and dramatic variations; dhalang Purbo Asmoro is, according to Asia Society’s program notes, “at the forefront of the modern, classical interpretive treatment” of wayang. Reportedly he both embodies the 900-year-old traditions of the form, which has been recognized by UNESCO as a “masterpiece of human heritage,” and also adopts contemporary innovations, while standing above recent trends to trivialize the art or render it unfamiliarly avant-garde.

However, the story drawn from the Hindu epic Mahabharata is neither familiar to most Westerners nor compelling to audiences conditioned to fast-paced editing and computer generated imagery. Bahasa Indonesia is incomprehensible to most Americans so Asmoro’s inflections, asides and word-play were lost on us (Kathryn (Kitsie) Emerson is amazing at the simultaneous translation, howver, keying it into the computer as quick as Asmoro spoke) . The tale’s humor and puppets’ knockabout tiffs seemed roughly as sophisticated as a Three Stooges routine. Time didn’t have our accustomed pace.

Yet the shadow theater and gamelan experience is worthwhile precisely for taking us from our usual entertainments. For a while I sat in a front row, two yards at most from the orchestra, and became immersed in the shimmering net of sonic ribbons and knots, dynamic intensities and relaxations created almost exclusively by the synchronized percussion. Â If I didn’t understand the puppet master’s nuances, I could admire his handwork, commanding stick figures to bob and weave, strike poses of pride and humility. I wasn’t on the edge of my seat concentrating on psychological realism, but no one suggested that I should be.

With audience members coming and going, people of all ages walking up onstage to view the puppets as they’re viewed in Java and Bali, shadows on a screen, a welcomed informality reigned.

The Asia Society provided food and drink and places to sit and chat outside the theater, in emulation of the festive, neighborly atmosphere wayang kulits create at home. In shadow puppet and gamelan shows, there is apparently no fourth wall.

Herbie Hancock, keytar master

The Herbie Hancock who concertized at Jazz at Lincoln Center last Saturday night was the casually joking yet research-minded fusion meister. A review of his Friday night concert by Jon Pareles in the New York Times takes a generous view of Hancock darting among his multitude of possibilities, but I was less taken by his next evening’s mostly greatest-hits show. I think Hancock underplayed his true piano genius.

Over a two-hour period, the 72-year-old prodigy played only one piece through concentrating on the Fazioli grand, which seemed so bright and hyper-responsive to his touch as to nearly replicate the sound of the electric Fender Rhodes Suitcase Piano he used in the early 1970s (sans the vibrato effect and inherent Rhodes fuzziness). Here’s a taste Herbie playing Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” the Faizoli at last January’s NAMM (Nat’l Assoc. of Music Merchandisers)Â convention —

Compare with this demo of the ’70s electric:

Several times during the Jazz at Lincoln Center show Hancock turned to his grand turned after establishing a song on his Korg Kronos synth. Several times he strapped on his Roland AX-7, which has (according to Wikipedia) “a pitch-bending ribbon, touchpad-like expression bar, sustain switch, and volume control knob, all on the upper neck of the instrument” where a guitarist would fret, were this a guitar. The AX-7 has an exceptionally broad range of high and low notes, which Hancock deployed spectacularly during a duet with electric bassist James Genus — the two musicians went lower and lower, faster and faster. However, it also has a lot of cheesy sounds, ostentatiously blaring and without the natural fade out (decay) of a piano’s taut wires hit by felt hammers. And since the keytar involves its player’s right hand principally to play single note runs, Hancock’s brilliant harmonic abilities were rather reduced. It struck me he might as well have been blowing an amplified melodica.

I didn’t recognize the one acoustic piece he performed, unaccompanied — it may have been impromptu. However, his version of “Watermelon Man” (originally popularized in 1963 as a boogaloo by conguero Mongo Santamaria) reprised Hancock’s 1973 arrangement for his jazz-rock Headhunters, a prominent second theme juxtaposed against the main line. Except at JALC, instead of using an intro derived from Central African Pygmy’s hocket-like hindewhu singing/blowing, Hancock led in with his guitarist Lionel Loueke’s composition “Seventeens.” Loueke was quick and nimble in exchanges with Hancock, who has adopted his late mentor Miles Davis’ manner of stepping right up to and into the face of his sidemen while they’re interacting. Drummer Trevor Lawrence, however, was isolated up a raised platform toward the back of the stage, and pounded out grooves without much of the forward propulsion formerly revered as “swing.”

Was this what was called for on the occasion of Hancock’s debut at the House that Wynton Built? Marsalis, after all, did his first prominent recording as a member of Hancock’s quartet (with Ron Carter, bass; Tony Williams, drums) in 1982. That was an all-acoustic affair, their album comprising Monk’s “Well You Needn’t” and “‘Round Midnight” as well as Hancock’s “The Eye of the Hurricane,” part of his Maiden Voyage suite, and “The Sorcerer” which he’d written for Miles Davis to record in 1967. At Rose Hall, before a Jazz at Lincoln Center audience including many fans who’ve followed him since the ’60s, Hancock relied on his best-selling, not his most beautiful, compositions.

Besides “Watermelon Man,” he offered up a succinct version of his 1983 single “Rockit” which introduced dj-scratching to his repertoire (an element performed by Trevor Lawrence, apparently from a computer rather than a turntable). He performed a version of “Cantaloupe Island” Â based not on the luminous track from his 1964 album Empyrian Isles but rather on the sampled “Cantaloop (Flip Fantastia)” rendition Us3 sold to gold status in 1994.

Freddie Hubbard played a brilliant solo on the original recording and did it again with Hancock, Carter, Williams and Joe Henderson for the concert One Night With Blue Note in 1985. At JALC Herbie used his keytar and emphasized Us3’s wacka-jawacka acid-jazz underpinning, but here’s how he did it when on tour with guitarist Pat Metheny, bassist Dave Holland and drummer Jack DeJohnette in 1990:

No question that Hancock has a knack for catchy riffs that can be embellished over repeating hooky bass figures. Of course the finale was “Chameleon,” his ’70s Headhunters anthem that has by now launched two or three generations of jazz jams. It was another display of bombast over nuance, though as if to make that very point his entire ensemble got quiet as a whisper before blasting out the show’s last choruses.

“Chameleon” is the kind of melodic funk that’s easy to learn and like, same as “Watermelon Man,” “Rockit” and “Cantaloupe Island.” It’s rousing, and as Herbie Hancock plays it with keytar squiggles to a thumping backbeat, a sure crowd pleaser. But Hancock commands considerably more musical sophistication than this set-list represented. I’m all for jazz fun instead of fustiness — and I was sitting next to bassist/vocalist Esperanza Spalding, who clearly enjoyed Hancock’s oomph. But is it too much to expect that in the presumed temple of jazz purism the subtlest pianist in our land do something a bit more substantial?

Maybe so. Maybe next time.

Which Herbie Hancock comes to Jazz at Lincoln Center

Pianist Herbie Hancock is a chameleon — as I say in my newest column in CityArts-New York. For his first appearance at Jazz at Lincoln Center on Friday night (3/9 ) he leads a trio, and on Saturday (3/10) adds Benin-born guitarist Lionel Loueke,  in formats a far cry from The Imagine Project, Hancock’s latest album. In it he puts his skills as collaborator and accompanist to work with Pink, Seal, India Arie, Jeff Beck, John Legend, Los Lobos, the Chieftains, Chaka Khan, Toumani Diabate and diverse others. But here are three rare video examples of Mr. Hancock in decades past, with a fusion anthem, an experimental electronics-graced ensemble, and all stars playing the theme from his 1960s masterpiece, Maiden Voyage.

“Chameleon” by Hancock’s Headhunters, in Chicago, 1974:

“Sleeping Giant” by Hancock’s Mwandishi ensemble of 1972 (Herbie’s Fender Rhodes piano solo kicks in at 1:50)

And in 1986, revising his roots on the grand piano for “Maiden Voyage” featuring Freddie Hubbard, Ron Carter and Tony Williams from the original recording of 1965, plus tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson.

Composer Heiner (Brains on Fire) Stadler @ It’s Psychedelic Baby

Heiner Stadler is a lesser-known but fascinating New York City-based composer who’s stretched he structures and dimensions of jazz with

all-star productions including A Tribute to Monk and Bird and Brains on Fire (which I annotated for recent reissue). It’s Psycheledic Baby, the online magazine by Klemen Breznikar taglined “discover the unknown” has published an interview with Stadler — a Polish-born (’42) WWII refugee who heard a Sydney Bechet record when he was 13, got to NYC by boat in his 20s, broke but motivated. He says his composing has been as profoundly affected by John Lee Hooker as by Bach and Cage (and he’s produced recordings of them all). I wrote a few words of introduction to the interview.

Recorded from the late ’60s through late ’70s, Stadler’s pieces are often long and always multi-dimensional, even if his collaborative improvisers are just two (cf, Dee Dee Bridgewater’s virtuosic 20-minute “Love in the Middle of the Air” over only Reggie Workman’s bass). All his records have been released through his own  Labor Records (might call it a label-of-love) and there’s not a lot of samples online tbut I found one youtube clip.

Unfamiliar to me, evidently excerpted — but from what? — I emailed Heiner for identification. He wrote back:

This is indeed one of my pieces, an excerpt from “Out-Rock,” part of my Jazz Alchemy cycle. K7 Records, a German company, had requested a license for this tune on behalf of “Four tet / DJ Kicks” in conjunction with the release of the act’s CD and double LP under the same name/title. The CD version of Out-Rock with added electronics was shortened to 1:38; the version on the 2-LP set is identical to the one on the Alchemy CD, namely 8:40.

As for the trumpet player, this was the late Charles McGee (whose name I had always misspelled by inserting the “h” after the “G”). Charles was a dear friend of mine practically from the time I arrived in NY City.

It’s Psychedelic Baby, Heiner’s music, Â jazz beyond “jazz.”

The President sings his hometown blues

President Obama is not to be forgiven for signing the heinous Nat’l Defense Authorization Act and several other bad moves, but as a blues fan I give it up to the guy for singing “Sweet Home Chicago” with B.B. King while hosting the first ever  White House blues party.

Obama’s version of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” was better,

and I can’t wait ’til he dips into the Marvin Gaye songbook (“What’s Goin’ On?”, not “Sexual Healing”). Singing must be how he won Michelle. Way better than Romney’s version of “America the Beautiful.”

Swiss jazzers occupy the Stone, East Village

European jazz stars of the Zurich-based record label Intakt come to the Stone, John Zorn’s serious recital room, for a two-week fest March 1 – 15 in which they’ll collaborate with veterans of NYC’s downtown improv scene.

March 11: from left, Andrew Cyrille duets w/ Irene Schweizer, and Oliver Lake (no Reggie Workman, sorry!) — photo credit sought! No copyright infringement is intended.

I detail some of the shows — and why people think jazz is better loved abroad than at home — in my new column in City Arts-New York.

It ain’t easy playing Mahavishnu, but Weston does it

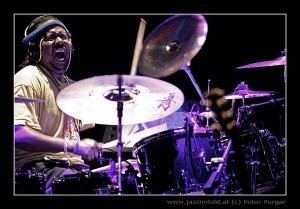

Guitarist John McLaughlin‘s Mahavishnu Orchestra was the highest-flying of any ensemble emerging from Miles Davis’ jazz-rock initiative in the early 1970s, establishing a previously unapproached standard of virtuosity, improvisational excitement and commercial success for all-instrumental electric bands to follow. Drummer G. Calvin Weston‘s Treasures of the Spirit quintet playing music of McLaughlin’s MO at the 92nd St. Y Tribeca in NYC last night (Feb 10, 2012) heroically addressed the complexity, speed and power of unique, difficult, enduring and compelling repertoire – a feat rarely attempted but inspiring to hear when musicians nail it, as Weston’s cohorts did.

With electric guitar Bill Berends, violinist Marina Vishnyakova, electric bassist Elliot Garland and keyboardist David Dzubinski addressing roles originally performed by McLaughlin himself (usually on a double-necked instrument), Jerry Goodman (still active, he’s been in the Dixie Dregs among other genre-confounding groups), Rick Laird (now Richard Laird, photographer) and Jan Hammer (composer for “Miami Vice,” Cocaine Cowboys, innovative computer animations and the first commercial tv network in Eastern Europe), Weston pounded out gloriously fast, muscularly emphatic rhythms to propel “Hope,” “One Word,” “The Dance of Maya,” “Open Country Joy”, “Triology,” “Dawn” and “Meeting of the Spirits” — multi-part compositions originally recorded on The Inner Mounting Flame (released in 1971), Birds of Fire (’72) and The Lost Trident Sessions (recorded in ’73, not released until 1999).  If it seems odd for a drummer to reprise material written for a frontline of electric guitar, violin and keyboards (including synth) plus electric bass, know that the original Mahavishnu Orchestra was driven by Billy Cobham, a contributor as essential to the group’s sound and prodigious four-year-run (reportedly 580 concerts during that period) as McLaughlin himself. (In fact, drummer Gregg Bendian also has an ambitious Mahavishnu Project -Redefined , which coincidentally had a booking scheduled for tonight (Feb 11) in New Hope, PA — postponed due to icy roads in the region).

Obviously Weston digs Cobham. He showed up in Tribeca with a vast array of tom-toms, cymbals, a gong and double bass drums, akin to the kit Cobham eventually employed. Weston’s beats were true to Cobham’s models: solidly struck, whip-snap fast and precisely fulfilling the unconventional time signatures derived from Indian tabla practices which gave the Mahavishnu Orchestra its distinctive motivation. But Weston has his own shtick, too. Among his skills:

- ferocious press rolls on his snare, but also with his two feet on the kick pedals;

- Â independence yet also paired coordination of his four limbs;

- ability to throw in fills and accents where there wouldn’t seem to be time to put them;

- mastery of the different pitches/timbres of all those cymbals and toms;

- control of dynamics so that there’s always a notch up-the-scale to go,

- and with bassist Garland an instinct for bringing the lowdown funk out of Mahavishnu material initially intended for seeking a transcendent spiritual plane.

Weston directed all the action from his seat in the manner of drummer-bandleaders like Art Blakey and Jack DeJohnette. At 52, he has enviable reserves of energy. He turned what had been advertised as two sets into one long one, throwing punches for two hours continuously like a determined boxer who doesn’t hear the bell tolling that he can rest between rounds.

Although the Mahavishnu Orchestra was brilliantly conceived to flow from classically-stated themes to raging collective jams, soft, folkish or raga-like passages to competitive call-and-response episodes, it was the bodacious end of its sonic spectrum that most engaged listeners in the ’70s and has wowed us ever since. Not that the MO was just loud, though it was indeed loud. The MO was on fire, with neatly shorn, pale, earnest, white-clad young McLaughlin, a disciple of Sri Chinmoy (who gave him the name “Mahavishnu” after the Hindu creator/destroyer/preserver of the universe) at its center, engaged yet serene. He excelled at articulating strange scalar lines and bent notes in upper octaves at speed-metal tempi, while violinist Goodman bowed quickly also in top registers and Hammer bent or pushed pitches where newly developed synthesizers had never gone before.

Berends, Vishnyakova and Dzubinski worked the same angles to nearly the same affect. There were minor, easily forgiven fluctuations of intonation, and by definition they weren’t the originators of the MO vision, so the question sometimes arose: Whose music is this? Weston’s Treasures of the Spirit last night was not so visually imposing as its predecessor: The players wore street clothes, and Berends bears a resemblance to Penn Gillette wearing a pirate bandana, rather than McLaughlin the handsome Yorkshireman pure as snow aspiring to eternal bliss.

Well, it’s no longer 1971, and the shock of hearing musicians reach with hedonistic rock fervor for the holy unattainable is gone for good. The small crowd at the Y, a multi-use facility with excellent performance space but off the nightlife track, seemed to be predominantly men who remember hearing Mahavishnu in their youth and have not gotten over it (like me). That’s unfortunate, because this music — not just its imagery and mythology — Â as Weston & Co. put it forth should appeal to ravers of all ages, anyone looking to pump it up.

G. Calvin Weston’s other associations are certifiably hip: He’s recorded and toured with Ornette Coleman’s amplified double quartet Prime Time, been in the Lounge Lizards, the Free Form Funky Freqs with Vernon Reid and Jamaaladeen Tacuma and on the Get Shorty soundtrack. In each context he strives for the personal satisfaction of making music live, immediate and interactive as possible.

If Treasures of the Spirit has a flaw, it’s that the band sometimes moves less than persuasively through the pastoral, contemplative moments McLaughlin planted in his pieces for introduction, punctuation and contrast to the urgency Weston wants to convey about time passing inexorably, now. Time is moving fast, there’s no way to stop it and we don’t exactly catch up by reaching back 40 years to remembered pleasures. But revisiting, restoring and reviving music that was born years ago but has lost no vitality doesn’t feel like a desperate attempt to recapture an era so much as a statement of faith in the value of that music then and in the present. Jazz — fusion-manifestations included — is made in the moment and if the sounds fit those who play it and hear it, they are indeed treasures of the spirit. I came home from G. Calvin Weston’s show enriched by people out here collaboratively lifting earthy rhythms and searing melodies to the open sky.

Goin’ on about “free jazz” and “the avant-garde”, w/playlists

Jose Reyes of the online listening station Jazz Con Class has posted  a Q&A with me about “free jazz” and “the avant-garde” — which he proposes as two distinct subgenres of jazz, tied to the 1960s.

New things — innovations — thinking outside the box — breaks from conventions and the continuum of progress (evolution) — these issues are regards jazz, among other art forms, has long fascinated me. It’s the topic of my book Miles Ornette Cecil – Jazz Beyond Jazz and the inspiration of this blog. So I spin out more of my pov about these matters in response to Jose’s questions, and I hope you’ll enjoy them while listening to the playlists he’s set up — but comment on the Q&A discussion below, or on my Facebook post of this blog posting.

American novels: as fun to write as they are to read?

Broderick Crawford as populist pol Willie Stark in Robert Penn Warren’s All The King’s Men – Law&Liberty.org

Of 10 American novels critic Terry Teachout posted yesterday that he wishes he’d written, only All The King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren similarly appeals to me. I can imagine hunkering down as Penn Warren did, dryly but fiercely etching the sickness of American populist politics, which we’re seeing swirl at its sickest this very  primary season. It would be work, for sure, but at a white hot energy — which I’d think would be hard to sustain, but so satisfying to bring to completion.

I haven’t read all Terry’s other choices (but of course Gatsby), and as he says his whimsical exercise is based on personal taste. Would it have been fun to write Gatsby? Maybe for F. Scott Fitzgerald, but not for me. I’d rather have dreamed up the terse treachery in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, the flat-out funny of Max Shulman’s Barefoot Boy With Cheek, the kaleidoscopic enormity of

Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow.

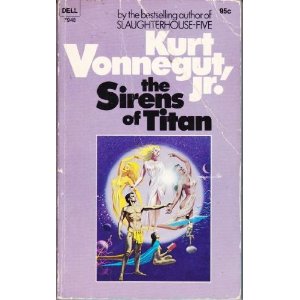

I’d have enjoyed penning “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle” (not novels, I know, but then neither is “The Tell-Tale Heart”; the three of them together = a novella, so I’ll claim them) and Sirens of Titan and would be proud (of course) to have authored Huck Finn. Tropic of Capricorn is another I could, when I read it, fantasize that someday I might come up with with something like. Octavia Butler’s Wild Seed is excitingly vivid and visionary — just think of spending time conjuring flawed but fantastic immortals in paranormal conflict. Elmore Leonard’s Killshot — Elmore always has fun when he’s writing, you can tell. And maybe Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams, though I have nothing like the grasp of time and space (physics, right?) I’d have had to have for that.

I’d have enjoyed penning “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” and “Rip Van Winkle” (not novels, I know, but then neither is “The Tell-Tale Heart”; the three of them together = a novella, so I’ll claim them) and Sirens of Titan and would be proud (of course) to have authored Huck Finn. Tropic of Capricorn is another I could, when I read it, fantasize that someday I might come up with with something like. Octavia Butler’s Wild Seed is excitingly vivid and visionary — just think of spending time conjuring flawed but fantastic immortals in paranormal conflict. Elmore Leonard’s Killshot — Elmore always has fun when he’s writing, you can tell. And maybe Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams, though I have nothing like the grasp of time and space (physics, right?) I’d have had to have for that.

I admire a gazillion other American novels (and many foreign ones, too), but couldn’t have turned out The Turn of the Screw or Moby Dick or The Scarlet Letter or An American Tragedy or Invisible Man or Miss Lonelyhearts or Donald Newlove’s fantastic Sweet Adversity (much less his latest, Kindle-only, 1000+ page Starlight Photoplays) or Robert Coover’s The Origin of the Brunists or Naked Lunch or even Portnoy’s Complaint — but gee, if I could! Just one of the not-so-simple Dr. Suess classics, W.R. Burnett’s iconic Little Ceasar or James Cain’s Double Idemnity (the Amerian Crime and Punishment) or Christopher Buckley’s The White House Mess or gosh, Carl Haissen’s Tourist Season — sitting at the keyboard, knocking any of those out — that would be a kick. I don’t know if John Burdett’s Bankok trilogy counts as an American novel, exactly, or if Mezz Mezzrow’s Really the Blues is a novel, though it’s ultra-American. Like The Freelance Pallbearers, My Life and Hard Times and (back to Twain) No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger or Algren’s The Devil’s Stocking or The Wizard of Oz. To dwell within such books while they’re unfolding, that must be what novelists live (and die) to do.

1000+ page Starlight Photoplays) or Robert Coover’s The Origin of the Brunists or Naked Lunch or even Portnoy’s Complaint — but gee, if I could! Just one of the not-so-simple Dr. Suess classics, W.R. Burnett’s iconic Little Ceasar or James Cain’s Double Idemnity (the Amerian Crime and Punishment) or Christopher Buckley’s The White House Mess or gosh, Carl Haissen’s Tourist Season — sitting at the keyboard, knocking any of those out — that would be a kick. I don’t know if John Burdett’s Bankok trilogy counts as an American novel, exactly, or if Mezz Mezzrow’s Really the Blues is a novel, though it’s ultra-American. Like The Freelance Pallbearers, My Life and Hard Times and (back to Twain) No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger or Algren’s The Devil’s Stocking or The Wizard of Oz. To dwell within such books while they’re unfolding, that must be what novelists live (and die) to do.

Well, I’m not too shy or superstitious to admit I still harbor novelistic ambitious. I’ve got a complete draft of a fast-paced, hiply talkative crime novel (if anyone’s interested, leave a comment below), notes  for a long work on an underground movement in a dystopian future and a couple old, extremely fanciful chapters of a backwards odyssey in the ’60s, if it had been completely different. I intend to shape all these up, finish them, publish them. True, novels take time, but they make time for the writer and the reader — that suspended bubble of the moments (hours, years) spent writing and reading. I’m sure it’s time well spent, ’cause look at what worlds they depict, so easily accessed and fully inhabited, how wondr’ously eternal yet marvelously new they are every time I open the covers. For sure the kind of novels a person likes –Â loves — say a lot about the person. A poet, not a novelist, said it: “I am large, contain multitudes.” Not to be grandiose –when I feel that way it’s from reading all these novels. . .

for a long work on an underground movement in a dystopian future and a couple old, extremely fanciful chapters of a backwards odyssey in the ’60s, if it had been completely different. I intend to shape all these up, finish them, publish them. True, novels take time, but they make time for the writer and the reader — that suspended bubble of the moments (hours, years) spent writing and reading. I’m sure it’s time well spent, ’cause look at what worlds they depict, so easily accessed and fully inhabited, how wondr’ously eternal yet marvelously new they are every time I open the covers. For sure the kind of novels a person likes –Â loves — say a lot about the person. A poet, not a novelist, said it: “I am large, contain multitudes.” Not to be grandiose –when I feel that way it’s from reading all these novels. . .

Lone wolf sax composer Tim Berne peddles Snakeoil

Alto saxophonist and staunchly original composer-bandleader Tim Berne’s new album — his 41st, but first on a label as internationally prominent as ECM since he put out two scorchers for Columbia in the mid ’80s — has the strange title, Snakeoil, meaning b.s., originating in the sale of quack medicines. This must be part of Berne’s self-deprecating, somewhat detached and perhaps sardonic temperament. But then he’s always been a bit of a lone wolf, going his own way, as I write in my newest column in CityArts-New York, just before he embarks on a rare 11-city US and 9-city European tour (starting at Regatta Bar, Boston on Feb 16, the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art Feb 17).

There’s nothing fraudulent about Berne, it must be said from the start, any of his past music or this particular album, which is another (his 41st) uncompromising demonstration of what musicians come up with when they think for themselves about beauty — which seems to be his chief concern. Berne’s tone on alto, to begin with, is exacting while ranging moodily from plaintive clarity to steely assertiveness. His compositions are not slick or glib — they are rather long, multi-dimensional and demand genuine engagement of all the musicians involved, rewarding most those listeners who pay full attention, free of suppositions, to the sheerly sensual fluctations of of sound and the players’ interactions. With no bass, rigorous-as-chamber-quartet attention to detail and the patented ECM sonic treatment delivering the tonal richness all the instruments (besides Berne’s sax, Oscar Noriega’s clarinet and bass clarinet, Matt Mitchell’s grand piano and Ches Smiths’ traps and other percussion), the composer’s concept and ensemble’s realization are presented with utmost honesty.

This is how the music is meant to sound, you become convinced, how the musicians hear it in their minds, so pressing they have to get it into the air (and they’re enormously lucky to have it so documented). Their music, for all its obvious framework, also seems to spring from them spontaneously – Noriega’s clarinet, in particular, has episodes of venturing forth all but unaccompanied, toeing a thin line of naked uncertainty that lures the ear along in suspense ’til he connects (gasp! — how?) with a resolutely structured (though still far from conventional) part of the song.

Berne’s efforts have always been for serious contemplation. I don’t know of any of it you (or at least I) could dance to, but the alternative to rockin’ rhythms and ecstatic riffs has its compensations. Follow these pieces and you slip through dark woods, roam the lip of a cliff looking down a ravine, removed from any referents to easy pop culture, the way things dully always are, the usually inescapable context of urban life.

Snakeoil has a Nordic quality, as do many ECM records — meaning they’re more cooly incisive than hot and heedless. Well, over the course of a 35+ year career, Berne has evaded the traps of predictablity, being tamed or de-toothed, and that’s an achievement to be admired, in part because it’s so hard for musicians coming up today to emulate. On the other hand, Berne is not now and has never been withdrawn, musically. He plays well with others: Bill Frisell, Hank Roberts, Herb Robertson, Tom Rainey, Craig Taborn, Michael Formanek, David Torn and Chris Speed have been among his most reliable collaborators, and represent an enlighted circle. He also gets them to play well with him.

That’s a rare strength for a lone wolf, but then you’ve got to figure that a survivor of 35+ years independence in an art form already as out in the territories as jazz is by Darwinian precepts and definition an alpha. He doesn’t bite, but he suffers no foolishness either. It’s tough being an outsider, trying to get heard. But dig, Snakeoil aint’ hardly about selling.

“Organ Monk” weds funk & Thelonious, soul and smarts

Organist Greg Lewis, wearing a monk’s robe, plus guitarist Ron Jackson and drummer Damion Reid,  tore up with full respect the knotty compositions of the late great Thelonious Monk last night at 55 Bar in Greenwich Village. About a dozen people heard them over a 90 minute period (they played a full set, took a break and performed one more extended tune before turning the stage over to guitarist Mike Stern) but it was one of the most enjoyable sets I’ve caught for months.

tore up with full respect the knotty compositions of the late great Thelonious Monk last night at 55 Bar in Greenwich Village. About a dozen people heard them over a 90 minute period (they played a full set, took a break and performed one more extended tune before turning the stage over to guitarist Mike Stern) but it was one of the most enjoyable sets I’ve caught for months.

Playing a Hammond C-3, which he explained was a B-3 restored and put into a (somewhat) more easily transportable cabinet, Lewis demonstrated complete mastery of Monk’s penetratingly insightful, somehow intuitive melodies and startlingly flexible rhythmic structures. While the music of Monk has become iconic for jazz modernists as Bach’s is for classicists of the Western European tradition, generating tribute albums from talents as disparate as Wynton Marsalis and Hal Willner, Lewis’s interpretations capitalize on the reedy sustain of his instrument to highlight the “ugly beauty” (Monk’s term) in the songs’ often close-interval riffs and “wrong is right” (another Monkism) chords.

Lewis improvised excitingly, opening up “Little Rootie Tootie,” “Evidence” and “Think of One” among other tunes with dazzling fast finger runs and emphatic clusters, sometimes quoting other Monk songs in the midst of the one his trio was addressing. Jackson’s thick, clear tone and flowing solos admirably matched  Lewis’s interpretations and Reid, a last-minute sub for the trio’s usual drummers, was also fully aware of the repertoire’s quirks, adding his own intense energy. Mentioning he’s recently performed and/or recorded with saxophonists Steve Lehman, Steve Coleman and Rudresh Mahanthappa and trumpeter Nicholas Payton, Reid is in demand and his playing showed why.

Lewis’s album Organ Monk made my 2010 best of the year list, and I’m still listening to it (he’s recorded a followup, which awaits final mixing and release). A native New Yorker whose father David Lewis was a jazz pianist, Lewis plays Harlem venues including Showman’s Lounge and the Lennox Lounge where pretensions gain no traction but expressive soulfulness is prized. He claims organist Larry Young as his main instrumental influence; Young (1940-1978) was arguably the last organist to reframe his instrument’s potential (on both his own albums and with Tony Williams’ Lifetime). Lewis takes the advanced keyboard technique and free-thinking Young espoused (and others including Joe Zawinul, Don Pullen, Andrew Hill and John Medeski have each in their own ways have demonstrated) to compositions which boast distinct integrity, retaining the bluesy drive and church-redolent atmospherics of the first generation jazz organists (post-Waller and Basie, Wild Bill Davis and Milt Buckner leading to Jimmy Smith). And Lewis with Jackson and Reid (on the Organ Monk record, Cindy Blackman drums) are impassioned. All of which added up to breakthrough music, enriching and fun, jazz and beyond jazz.

Etta James and Johnny Otis — Jazz Masters?

Etta James, who died today Jan. 20 at age 73, and Johnny Otis, who died Jan. 17 at 90,

are rightly recognized as innovators and icons of American rhythm ‘n’ blues and soul.

But the jazz world — listeners, broadcasters and journalists, musicians and institutions up to and including the NEA — would be well-served to proclaim that Etta James and Johnny Otis are “jazz masters.” Their sub-genre identities remain within the greater mainstream of Afro-American music born about a hundred years ago, with blues becoming ever less a so-called “folk” form by engaging with other  musical and commercial influences, leaving rural isolation for urban hubbub, diverse developments and the ear of the world. Furthermore, Otis’s and James’s specific sounds emerged from America’s unique swing era stylings, in response to and generation of post-WW II U.S. cultural norms. As one with jazz.

Why would it matter if we called Otis and James “jazz masters”?

- It would emphasize the structural girding jazz has provided for the past century  to all of American popular song. So pop audiences would be encouraged to recast their “jazz as dead” stereotype, comforting current jazz artists who complain they can’t make it ’cause their music is chained to the “n-word”. Indeed, such jazz musicians might learn something from Otis’ business sense and James’ dismal history.

-  If we don’t recognize people like Otis and James on some official level as jazz masters, then as what? Heritage artists? That designation has been coded to mean ultra-traditionalists and conservationists. Nothing wrong with that — but Otis and James were more involved  with updates, revisions, hybrids, popularizations and other pragmatics of music-making than in revering its glories or protecting its legacies. They’ve been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Blues Hall of Fame — fine and good, such recognition and honors for their links to jazz aren’t mutually exclusive. It’s beneficial to admit that categories aren’t rigid. Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown was a jazzman, too.

- Johnny Otis and Etta James were jazz musicians from the start — jazz was their inspiration. Understanding them as such provides us with a truer vision of the breadth of jazz and its manifestations. It also prods us to enjoy their music in more depth, to take in its subtleties and appreciate the art.

Johnny Otis had six years of big band jazz experience before he convened his own 16-piece ensemble in 1945. The distance between mainstream jazz (if not that new thing, “bebop”) and pop music for dancing was quite close then. Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, Billy Eckstine, Tommy Dorsey,  Bob Wills, Ella Fitzgerald, Big Joe Turner and Louis Jordan were among the genuinely popular stars of jazz.  Otis could hang with them; he  drummed with Lionel Hampton on “Flyin’ Home” as the climax of a 1950 broadcast, 24 minutes into the program —

Etta James wanted to be Billie Holiday. Holiday’s influence is palpable in all of James’ ballad singing, including her version of “At Last” (originally recorded by Glenn Miller and his orchestra)  — it’s in the way Etta phrases, hesitating behind or jumping ahead of the beat, how she wrings lyrics for layers of meaning and employs all the qualities of her voice despite a fairy limited octave range for nuance. James won a Grammy for Mystery Lady: The Songs of Billie Holiday, and in her 2006 album All The Way she’s as credible with that Sinatra signature song as with Lennon’s “Imagine” and “What’s Goin’ On?” That’s a jazz artist’s adaptability. And though it was rare for her to record with swing-oriented backup, though she shouted out upbeat messages with gospel fervor rather than float through melodies like a horn, Etta James could improvise just fine, as when she joined Glady Knight and Chaka Khan, backed by B.B. King, in the Bessie Smith classic “T’aint Nobody’s Business,” which Billie Holiday also sang.

Otis and James were musicians who projected no pretense of performing high art, experimenting or abstracting. Â They were on-the-road entertainers who, if they lacked probing and profound repertoire yet depended upon consistently performing real live music people would flock to and pay for night after night, everywhere, in pursuit of being made more relaxed, happier, less blue — transformed. Otis, in particular, was alert to trends in taste and the talented people who could fulfill listeners’ desires, and discovered several singers including Etta James but also Esther Phillips who brought jazz-derived edge to bluesy pop material. James was a balladeer for the working class, never very glamorous, often in her early work raunchy or a victim, but touching because she put emotions in her voice that rang so true.

Johnny Otis and Etta James may have ended up as the Godfather of R&B and the First Mama of Funky Stuff, but when they started those categories didn’t exist. They toiled in the fields of popular jazz. That they affected change in popular music coming from such background and never dishonoring it means, to me, Â they were masterful enough to focus elements of the jazz arts into music of wide appeal, gathering audiences from across formerly divided demographic groups, turning definitions that hewed to conventions on their head.

Johnny Otis and Etta James may have ended up as the Godfather of R&B and the First Mama of Funky Stuff, but when they started those categories didn’t exist. They toiled in the fields of popular jazz. That they affected change in popular music coming from such background and never dishonoring it means, to me, Â they were masterful enough to focus elements of the jazz arts into music of wide appeal, gathering audiences from across formerly divided demographic groups, turning definitions that hewed to conventions on their head.

Let me be clear: I am not suggesting that the National Endowment of the Arts issue posthumous honors holding up Johnny Otis and/or Etta James as embodiments of jazz originality or virtuosity. But I do submit that popular artists who employ jazz strategies, techniques, tactics, materials and values are also part of the jazz spectrum – as today the jazz industry (what’s left of it) and press (ditto) includes under the greater jazz umbrella, sometimes grudgingly, Kenny G., Boney James, Najee, Soul Live, Diana Krall, Tony Bennett, Jamie Cullum and countless others.

If we don’t, maybe we should. Because counting their sales boosts the bottom line on overall interest in jazz, and makes a mockery which is well-deserved of definitions which only have to do with marketing. Because playing them in a jazz radio show demonstrates the connections between the earthy and the esoteric. Because music is a stylistic continuum, and not series of separate bins.

If it’s vernacular music made in America since the 1920s, derived from African-American traditions and urban circumstances, engaging primarily with the marketplace rather than the academy or conservatory, depending upon knowledgable musicians to make it good in real time — then I say it’s fair to call it or at least reasonable to say it’s been informed by “jazz.” Whether you agree or not, please hail Johnny Otis and Etta James, find some of their music to listen to and dig.

Â