Photo-journalist Marc PoKempner, a long-time collaborator and one of my bffs, has a clear eye as well as a sharp ear for music. He captured some of the diversity and vigor of the 35th annual Chicago Jazz Festival, August 28 – Sept 1 Â 2013.

Click on these photos for the better, enlarged view.

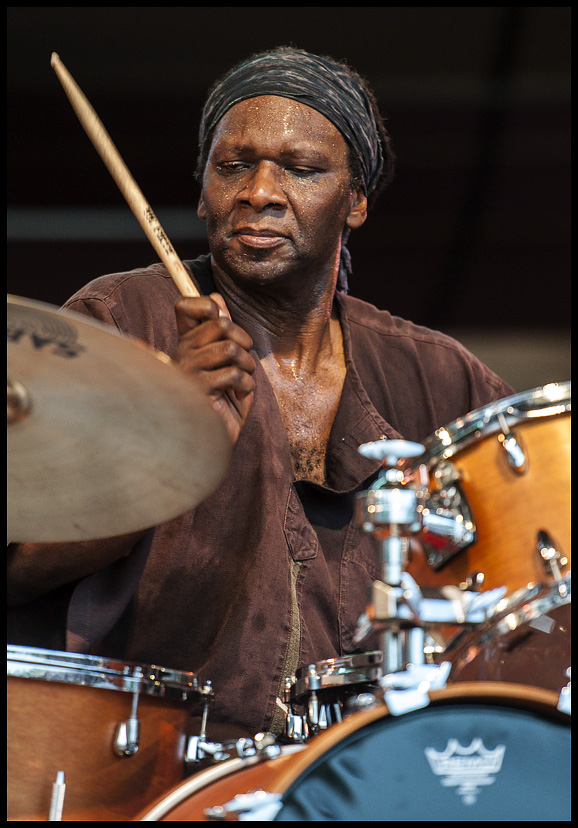

Drummer Hamid Drake, Artist-in-Residence, 35th annual Chicago Jazz Festival

(photo by Marc PoKempner)

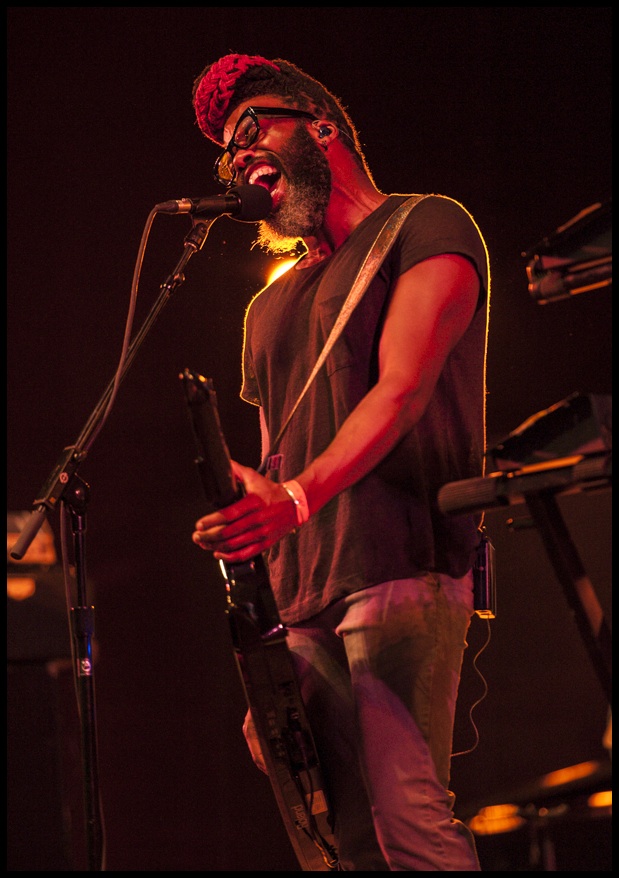

Saxophonist Ernest Dawkins @ Norman’s Room 43, Chicago Club Tour — Dig the night light

(photo by Marc PoKempner)

Rudresh Mahanthappa’s Gamak Quartet on the Jumbotron: Dave Fiuczynski gtr, Francois Mouton bass, Dan Weiss drums

(photo by Marc PoKempner)

Gamak takes a bow: Dave Fiuczynski, Rudresh Mahanthappa, Francois Mouton, Dan Weiss

(photo by Marc PoKempner)

Donald Harrison leads New Orleans Mardi Gras Indians for Chicago Jazz Fest finale (photo by Marc PoKempner)

Alto saxophonist Harrison, sitting in with saxophonist/trumpeter/flutist Ira Sullivan and pianist Willie Pickens, bassist Dennis Carroll (and the ghost musician?)

(photo by Marc PoKempner)

Marc knows what he likes: Irresistible dance music and genuinely moving what-have-you. It’s always fun to ride with him, looking and listening.

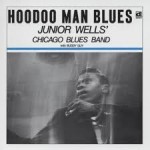

Art Ensemble of Chicago, but here performs with the sole document of tenorist Fred Anderson’s young quartet. All the AACM records are very different: Song For is fiercely expressionistic.

Art Ensemble of Chicago, but here performs with the sole document of tenorist Fred Anderson’s young quartet. All the AACM records are very different: Song For is fiercely expressionistic.