Annie Ross, who died July 21 at age 89, sold “Loch Lomond” as a seven-year- old in the Little Rascals with brass equal to her hero in “Farmers Market” hawking beans. The child of Scottish vaudevillians, she was maybe never shy. In 2002 I reported on her last stand with fellow vocalese icon Jon Hendricks, at the Blue Note in Manhattan for the newspaper City Arts.

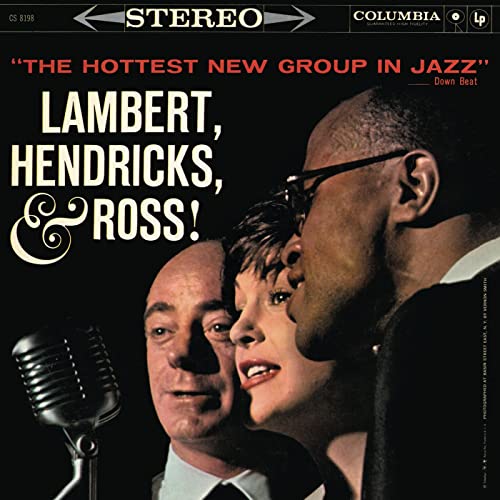

The second-to-last set ever to be sung by Hendricks and Ross, two-thirds of the vocal trio once hailed as “the hottest new group in jazz” was delightful, sad, instructive and substantial, all at once.

Annie Ross, a doyenne of lyric interpretation, and Jon Hendricks, a bard of bop vocalese, appeared at New York’s Blue Note for five nights on a double bill with the quartet New York Voices, in what was publicized as their final goodbye after decades of chilly relations. Hendricks had been less than discreet, and perhaps given to exaggeration, about some of his partner’s old bad habits in an interview for an English newspaper. Ross, probably best known in recent years for her role as a seen-it-all, done-it-all saloon singer in Robert Altman’s 1993 film Short Cuts, had announced she’d take no more guff from the guy she’d first joined (along with the late Dave Lambert) in 1956 to “sing a song of Basie.”

Back then, English expatriate and child movie star Ross had already secured her reputation by putting witty narratives to saxophonist Wardell Gray’s solos on “Twisted” and “Farmer’s Market.”

She quit Hendricks and Lambert in 1962, relocating to London where she briefly ran a nightclub and worked in films and on television.

Hendricks, who grew up in Toledo, Ohio as a protege of Art Tatum, has enjoyed a varied career for half a century, highlighted in the ’90s by his portrayal of a trickster spirit in Wynton Marsalis’s oratorio Blood on the Fields.

Ross and Hendricks first reunited for a singing gig in 1999, and since then have come together for special bookings, to delve into Lambert, Hendricks and Ross material and do their own speciality numbers, as well.

So there were two complicated lifetimes of jazz singing onstage, supported by a self-deprecating rhythm trio led by guitarist John Hart, and though their voices clung together as close as braids of twine, the artists generated little warmth for each other — only professional regard.

Hendricks, dapper in tailored suit and bowler hat, made the announcements, and Ross, in a red dress, exuded the merest hint of aloof attitude. They began by trading choruses on the saucy “Home Cookin'”; she walked off for his forlorn but articulate version of “Just Friends,” and returned to race through “Charleston Alley.” Hendricks essayed one original tune in which he whistled up a winsome solo, pretending to play a conductor’s baton like a flute; he departed for Ross’s always amusing “Twisted,” which she acknowledged had gained new life through a recording by Joni Mitchell.

Then Ross nailed the hilarious, lugubrious novelty number “One Meat Ball,” and engaged Hendricks like a sparring partner on an upbeat, feisty blues. Their finale was a rampaging “Cloudburst,” on which each demonstrated an extraordinary grasp of rhythm, deftness of mind and quickness of tongue.

Neither Hendricks nor Ross has as much command of vocal tone as they did when younger, but that’s the inevitable exchange with age for experience. Character, gumption and personality they both showed aplenty.

at 2014 Jazz at Lincoln Center

They are veterans of a golden time for jazz, an era in which the music’s popularity was at an unsuspected peak, and its urbanity was unchallenged. They exemplify jazz’s sophistication, swing and, each in their own ways, class. They demonstrated enduring grit, if not chops, for the much younger and unstrained New York Voices to aspire to. Their final Sunday night performance, which started around 1 a.m., reportedly was just as strong. Aficionados of American song could only hope this unmatched duo will someday mend its rift, and that Jon Hendricks and Annie Ross might appear again as partners, if never more as friends.

Post-script: As the photo above by Sánta Csába Istvan shows, Annie Ross and Jon Hendricks seemed quite cordial when they met at a reception celebrating the National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters, at Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2014. He had been named an NEA Jazz Master in 1993 and Ross was so designated in 2010.