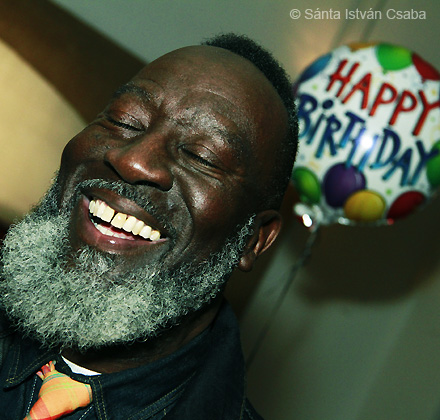

Ornette Coleman, genius musician and major inspiration to this blog and blogger, turned 84 on March 9. His son Denardo threw a family ‘n’ friends party in celebration, which I was privileged to attend. Denardo graciously allowed me to bring Hungarian photographer Sánta István Csaba, who created this portrait of one of the creative heroes of the 20th and 21st century (and all other photos on this page, except for Sound Evidence’s image of Ben Schacter and Jamaaladeen Tacuma).

Ornette Coleman, genius musician and major inspiration to this blog and blogger, turned 84 on March 9. His son Denardo threw a family ‘n’ friends party in celebration, which I was privileged to attend. Denardo graciously allowed me to bring Hungarian photographer Sánta István Csaba, who created this portrait of one of the creative heroes of the 20th and 21st century (and all other photos on this page, except for Sound Evidence’s image of Ben Schacter and Jamaaladeen Tacuma).

Ornette Coleman has exemplified the big, natural, fundamental idea of making music (and indeed any art, or for that matter life itself) as much as possible personal, responsibly collaborative,  free of constraints, spontaneous and open to emotional expression. He recognizes beauty everywhere and in everyone.

Denardo has played drums since age six, recording a full album, The Empty Foxhole, with his father and bassist Charlie Haden when in 1966, when he was 10 (ammd  it’s just been announced his Denardo Coleman Vibe will perform at the Prospect Park Bandshell in the Celebrate Brooklyn! festival on June 12, admission free). Back then his introduction to the scene caused controversy (everything Ornette did then caused controversy) and even outright derision, which has resulted in his being under-appreciated for decades. But that’s wrong. He long ago developed his unique skills and style, both at traps kit and as a key player in all projects harmolodic.

Denardo has played drums since age six, recording a full album, The Empty Foxhole, with his father and bassist Charlie Haden when in 1966, when he was 10 (ammd  it’s just been announced his Denardo Coleman Vibe will perform at the Prospect Park Bandshell in the Celebrate Brooklyn! festival on June 12, admission free). Back then his introduction to the scene caused controversy (everything Ornette did then caused controversy) and even outright derision, which has resulted in his being under-appreciated for decades. But that’s wrong. He long ago developed his unique skills and style, both at traps kit and as a key player in all projects harmolodic.

Denard’s fast moves, keeping of a constant pulse, dynamic approach to cymbals and lighter drum timbres provide significant propulsion to everything I’ve heard him do. For revelatory  listening, find Prime Design, Ornette’s full length composition for Denardo and string quartet, recorded at the opening of Caravan of Dreams in the Coleman family seat of Fort Worth, Texas, in 1987.

listening, find Prime Design, Ornette’s full length composition for Denardo and string quartet, recorded at the opening of Caravan of Dreams in the Coleman family seat of Fort Worth, Texas, in 1987.

Earlier — starting in the mid ’70s — Denardo had been at the core of Prime Time, Ornette’s combustible ensemble  of two electric guitars, two electric basses and usually two drummers he typically led while soloing on alto sax, violin and trumpet. That edition of Prime Time’s other principals — guitarist Bern Nix, bassists Jamaaladeen Tacuma and Albert McDowell, among them — also played with Denardo in the Firespitters, backing up poet/ nchantress Jayne Cortez, his mother. Except for that, Denardo has seldom performed without Ornette, a situation remedied at Celebrating Ornette! a spirited legacy tribute produced in Philadelphia on March 21 through the combined efforts of the Painted Bride, Philadelphia Jazz Project, Ars Nova Workshop, Bobby Zankel and  musicians organized by a Philly-based force unto the music world, aforementioned electric bassist extraordinaire Jamaaldeen Tacuma.

musicians organized by a Philly-based force unto the music world, aforementioned electric bassist extraordinaire Jamaaldeen Tacuma.

Denardo’s quintet had an innovative lineup: electric guitarist Charlie Ellerbee (another Prime Time vet), electric bassist McDowell (who Ornette had first plucked from a NYC high school band class) and upright bassist Tony Falanga (who had played an orchestral gig that afternoon) along with tenor  saxophonist Antoine Roney. Roney on tenor has a grainy, open-plains bluesiness reminiscent of Dewey Redman, Ornette’s longtime confrere, but even more Ornette-ish was Denardo’s concentration of activity in low registers.  Ornette has always had brilliant bassists (Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, Jimmy Garrison, David Izenzon, Chris Walker) and he likes to hear the bottom on top. Denardo’s three string-instrumentalists, who represented an enormous range of variety in their individual inclinations and sounds, tumbled around each other non-chalantly, shifting octaves and responsibilities for anchoring, soloing and counterpoint mid-improvisations.

Ornette has always had brilliant bassists (Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, Jimmy Garrison, David Izenzon, Chris Walker) and he likes to hear the bottom on top. Denardo’s three string-instrumentalists, who represented an enormous range of variety in their individual inclinations and sounds, tumbled around each other non-chalantly, shifting octaves and responsibilities for anchoring, soloing and counterpoint mid-improvisations.

McDowell was very much the electric bass guitarist; Falanga bowed with him, sometimes floating his pitches just above McDowell’s. Ellerbee played a  variation of r&b rhythm gtr chucka-chucka chords, introducing Ornette’s most famous theme, “Lonely Woman,” with an unaccompanied, abstracted, rubato melody interpretation had me imagining a person distraught unto despair, lost in the ozone, chilled to the existential bone. Falling in behind the deadpan Ellerbee, the band — spurred by Denardo — wailed.

variation of r&b rhythm gtr chucka-chucka chords, introducing Ornette’s most famous theme, “Lonely Woman,” with an unaccompanied, abstracted, rubato melody interpretation had me imagining a person distraught unto despair, lost in the ozone, chilled to the existential bone. Falling in behind the deadpan Ellerbee, the band — spurred by Denardo — wailed.

Jamaaladeen Tacuma — the most ecstatic, elastic, groove-laying, funkily free, deep electric bassist on the planet –followed with his For the Love of Ornette band (titled the same as his most recently released album, with mostly the same personnel). Ever since his mid ’70s debut (under another name) with Ornette on Dancing In Your Head, Jamaaladeen has been a bubbling spring of bluesy, out-bound movement, and his set starting with his “Tacuma Song” exemplified his style. Backed by powerhouse and tone-color-conscious drummer G. Calvin Weston, his frequent rhythm partner, JT established the catchy theme guitaristically on his blond Gibson ax his self-designed TacumART bass, then opened space for unrestricted solos by Wolfgang Puschnig on alto sax, Ben Schacter on tenor sax and Yoichi Uzeki, pianist.

These musicians seemed to revel in their opportunity to play before the full house (approx. 250) of Philly’s aficionados, devotees and performers (including pianist Dave Burrell) of Coleman-inspired arts. Uzeki, for instance, dismissed any contradictions implied by his classical training addressing the free jazz imperatives, applying a keyboard touch from spare to florid to the rambunctious group sound. Schacter, in from California, deployed a big, rangy tone that had some swagger, quoting several of Ornette’s famous motifs with reverent tenderness. Puschnig, an Austrian who in the ’80s co-founded the Vienna Art Orchestra, exemplified a cheerfully renegade approach to all his horn-playing, continuously spouting unpredictable melodies on alto as well as flute and hojak, a short Korean double-reed instrument.

The four players kept their minds on the songs that launched them, even while exploring how far those songs would take them away. They were fearless and intrepid — attitudes that were contagious, enlisting the listening crowd’s participation. The band performed the For The Love of Ornette title song, with spoken word by Wadud Ahmad, and some Coleman-penned curiosities, like the sketchy yet complete riff Jamaaladeen explained Prime Time had performed when guesting on Saturday Night Live.

\At least some of the basis of  Ornette’s love for Jamaaladeen was evident all the time: the bass guitarist has live-wire energy that surges confidently underwhatever sounds rise into the air. Nothing fazes him, and he can marshall fragments that might seem to issue from random corners into purposeful wholes.  Of the highlights: Asha Puhtli, the remarkable Indian-emigre diva who indelibly committed two of Ornette’s most ravishing songs on his album Science Fiction in 1971, crooned “What Reason Could I Give” for the first time in 40 years. The horns’ parts wrapped sinew-like around her rich, warm voice, JT coursing like blood aboil through it all, into a duet with Schacter that segued into a dramatic blues stomp and concluded with luscious chorale finale. Wow. Exhilarating. See it here.

Of the highlights: Asha Puhtli, the remarkable Indian-emigre diva who indelibly committed two of Ornette’s most ravishing songs on his album Science Fiction in 1971, crooned “What Reason Could I Give” for the first time in 40 years. The horns’ parts wrapped sinew-like around her rich, warm voice, JT coursing like blood aboil through it all, into a duet with Schacter that segued into a dramatic blues stomp and concluded with luscious chorale finale. Wow. Exhilarating. See it here.

Ornette Coleman wasn’t in the audience, but he was surely felt as present in the hall, brought by the artists and audience he’s affected to our core. “Denardo is Ornette’s son,” Jamaaladeen proclaimed after the drummer’s performance, “but we are, too,” he said, gesturing to his band waiting in the wings, and he could have opened the gesture up to include everyone convened (yes, also daughters).

Maybe he did — probably he meant to. It seemed like everyone there loved Ornette. As all people should: He’s a man who has freed music, for and within us.