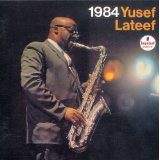

I’ll never forget (I hope) Yusef Lateef’s flute wafting out from the stage of  the 1973 Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival . . . Or his head-shaved, suited image on the cover of the boldly-named album  1984 (released in 1965, and not as dark as I’d expected) . . . Or his galvanizing spontaneous duet with percussionist Adam Rudolph at the 2010 NEA Jazz Masters concert at Jazz at Lincoln Center . . .

1984 (released in 1965, and not as dark as I’d expected) . . . Or his galvanizing spontaneous duet with percussionist Adam Rudolph at the 2010 NEA Jazz Masters concert at Jazz at Lincoln Center . . .

Indeed, Dr. Yusef Lateef enjoyed and shared with all who’d listen a fabulously creative, accomplished life to age 93, ending 12/23/13. He’d made music professionally starting when he was 18 in Detroit, and early on became a seeker and experimenter, eventually a scholar, philosopher and educator based at University of Massachusetts, Amherst.  I’m grateful to have encountered him in person, although I’ve respectfully disagreed with his indictment of the term “jazz” as defaming an art and discipline that he took to be humankind’s noblest expression. He acknowledged that he was from the jazz tradition, and I believe the many jazz people as high-minded as he was long ago saved the j-word from being saddled with negative connotations.

Lafeef called what he did “autophysiopsychic music . . . from one’s physical, mental and spiritual self, and also from the heart.” However his activities were categorized, whether his recordings were found in  hard-bop, soul jazz, New Age or world music bins — he always put his all into his efforts. Decades back, I was entranced by Lateef’s use of extended techniques, narrative solos and reed instruments from North Africa, the Middle East and Asia into relatively straightahead “jazz” formats, including Cannonball Adderley’s sextet.

Voice Prints, recorded in 2008 but just released, with Lateef making what I like to call jazz beyond jazz in a free-flowing collective quartet with percussionist Rudolph and fellow reeds and winds shamans Douglas Ewart and Roscoe Mitchell, is on my Best of the Year list.

Enjoy Lateef in duet with Adam Rudolph . . the two began working together in 1988.

and also with the estimable pianist Ahmad Jamal.

In November 2012 I saw Lateef sing the blues, play oboe, flute and tenor sax in the estimable company of saxophonist and vocalist Archie Shepp, bassist Reggie Workman, pianist Mulgrew Miller and drummer Hamid Drake at the Enjoy Jazz Festival, at the BASF Festsaal/Kammermusiksaal in Ludwigshafen, Germany. That concert was attended by all us cats presenting papers at the University of Heidelberg’s Lost In Diversity symposium on the “social relevance of jazz” (Lateef and Shepp addressed this topic, too, as did Alexander von Schlippenbach and Vijay Iyer), and a record of it may be  forthcoming. Provocative and serene, secular yet infused with an overarching faith, always bluesy but often transcendent — such were the sounds of Yusef Lateef.