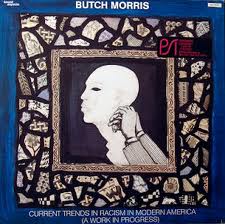

My maybe unpublished 25th anniversary liner notes for Conduction #1, Current Trends in Racism in Modern America, A Work in Progress, by the late Butch Morris with all-star improvisers, recorded 28 years ago today (Feb 1, 2013) and sonically as relevant as ever.

[The cast is: Frank Lowe, tenor sax; John Zorn, alto sax and game calls; guitarist Brandon Ross; harpist Zeena Parkins; cellist Tom Cora; turntablist Christian Marclay; vibraphonist Eli Fountain; pianist Curtis Clark; percussionist Thurman Barker; vocalist Yasunao Tone and Butch, of course, conductor. I understand that I’ve made a mistake about the multi-media/theater-installation piece “Goya Time,” which J.A. Deane, one of Butch’s longest and closest associates, calls Conduction #3 in his from-up-close tribute.]

Butch Morris: Current Trends in Racism in Modern America

When a full house of ardent downtown music followers flocked to the old Kitchen, a performance loft on Broome Street in Manhattan’s artsy Soho district on the cold night of February 1, 1985 to hear “Current Trends in Racism in Modern America” by Lawrence Douglas “Butch” Morris — I don’t recall if it was advertised as “Conduction No. 1” — no one knew what to expect.

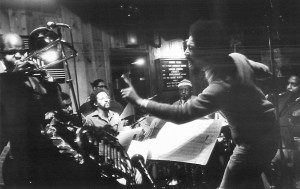

Butch Morris conducts David Murray band featuring trombonist Craig Harris, at Sweet Basil, circa 1987.

Photo by Lona FooteAt that time, as now, Butch was an inspired and productive presence on a diversified music scene populated by intersecting circles of extreme individualists. Where he fit in exactly was hard to discern, which is how he seemed to want it. He’d been actively performing solos, during which he might turn his cornet around to blow into its bell or upside down to get sounds by tinkering with its valves. He’d participated in flamboyant theatrical pieces, half-happenings/half performance art, such as “Goya,” wherein crowds circulated throughout a gymnasium-like space, prodded by actors costumed as if for the Spanish Inquisition, watching some dozen painters at work on canvases emulating “The Naked Maja,” while he himself led an ensemble sequestered in a sanctuary off a side-hall. He was also known for his collaborative relationship with David Murray, the tenor saxophonist and bandleader with whom Butch come to New York City from California just about nine years before.

Rather than being a full-bore, fire-breathing, high-energy expressionist like Murray, though, Morris went for nuance, suggestion and subtle colors in his instrumental performances, using space or silence like a sculptor. He had composed several lovely melodies, some of which David took as repertoire for his variously-sized bands, but Butch preferred to stay at the edge of the frame rather than in its center, or as the title of his first album (from 1979) put it, “in touch . . . but out of reach.”

All the while, as Morris has written in the liner notes to the extraordinary album Testament: A Conduction Collection, he was thinking of a way to “further develop an ensemble music of collective imagination — not in any way to downplay a soloist, but to have the ensemble featured at all times.” His doctrine was that “collective improvisation must have a prime focus, and the use of notation alone [is] not enough for the contemporary improviser.” From those precepts he had come up with the concept and term “conduction,” to signify both “conducted improvisation” and “the physical aspect of communication and heat.”

Both those phrases — conducted improvisation and the physical aspect of communication and heat — may be taken to describe not only to Butch’s musical concept but also current trends in racism in modern America, in 2010 as in 1985. Is it unrealistic or exaggerated to say that “trends” in day-to-day relations among Americans thinking and acting upon racial considerations are the results of behavioral improvisations of each individual so caught up? But also that individuals’ responses to issues of race are inevitably channeled, guided, conducted by social policies and historical forces? Certainly we acknowledge that physical aspects of “communication and heat” have fueled attitudes and assumptions regarding “race” since the founding of America and probably long before. Therefore, Butch chose a topic for Conduction No. 1 that was a perfect reflection of his musical method.

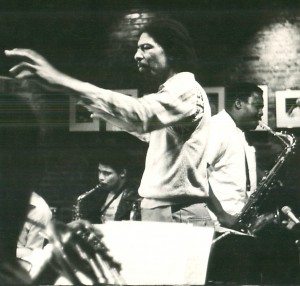

Butch Morris conducting Steve Coleman (left) and David Murray (right)l, at Sweet Basil.

Photo by Lona Foote.In this music, as in American race relations, individuals’ actions matter, but are simultaneously subsumed into a larger ensemble sound, a field of social projections. Particular individual and social reactions may be requested or even ordered, but not completely specified or successfully executed. To believe it’s possible to exert total control over an outpouring of music or advance of history is both illusory and by definition dictatorial. Those who live in the present, whether musicians and/or citizens, do what they can and what they will. Those who observe the activity from a point removed, be they social scientists or listeners, will choose or shift focus on the individual or the group, but will always have to contend with innumerable, mutable factors and will often be unsure whether individual or group best rewards or most requires attention.

Despite these conundrums, and though we don’t know what instructions Butch gave the ten all-star downtowners he assembled to enact his work, it’s tempting to describe Current Trends in Racism in Modern America programmatically, to create a story for it. Part One: A starting whistle springs a door open on a vast soundscape of scattered gestures and mutterings, which accrue more detailed density if not cohesion (and least of all, unity) as we plunge on. A single expression or two — John Zorn’s squawk against Frank Lowe’s talk-like phrases, for instance — give rise to an eruption of contentions, which is followed by a calm that’s soon beset by minor, then growing, irritations. Balm comes from the quietly riffing tenor sax and web of harp, marimba, resonate vibes. All chime in until a community debate develops, one voice (instrument) after another coming to the fore. A descending figure is established, and a beat box rhythm blares. Marimba and vibes fade on a whine that might be electrical, or crickets. Guttural efforts are swamped by dreamlike textures, which thicken until silence briefly falls.

Thereafter everything becomes more percussive, forceful, disassociated — random? Game calls squeal, rail and mew over piano chords from another planet. Is that crowing? The tenor sax calls out insistently and the cello echoes it, leading to another crescendo, an imposing, march-like backdrop, a pointilistic foreground, sweeping winds, repetitions which summon both concurrence and dissent. Dissension breeds expansion, an inclusion of more different sounds, some on the surface, some ringing and throbbing deeply, some tangling or spinning out. The affect is oceanic. We can only go with this flow, though it comes to no conclusion, simply cycling on and on . . .

Part Two, two-thirds shorter, is ostensibly more shaped by the conductor than Part One. Episodes stand out as if composed, not improvised. Isn’t that Butch’s intent, to blur the practices and question their intrinsic opposition?

But I stop there, because it’s foolish to impose any literal interpretation on a Conduction, better to dive in, opening your imagination to your immediate, personal responses. The music sounds different every time, anyway. Though recorded, it doesn’t seem frozen, probably because we aren’t listening from a fixed perspective ourselves, being always in flux.

In the history of improvisation, this is itself an achievement — perhaps the next radical step after Ornette Coleman’s very skeletally structured Free Jazz, recorded in 1960. What changed in the 25 years leading to Current Trends In Racism In Modern America? What’s changed in the 25 years between Conduction No. 1’s performance and this reissue of it? How will this music sound in another 25 years? We each have our own answers, but need direction to reach any reasonable consensus. In his music, Conduction No. 1 and elsewhere, Butch Morris won’t force his own views on us, but helps modern America and the world beyond hear what we each might have to say. — Howard Mandel, c 2010