Chicago bluesman Buddy Guy, at age 75 as wild a guitar pyrotechnician as lives today, and the British dinosaur rockers Led Zeppelin, whose guitarist Jimmy Page stands in Guy’s shadow, are being celebrated with Kennedy Center Honors, to be presented at a program at the Kennedy Center on Dec. 2. Remind me again why we’re giving awards to non-American pop stars?

Guy, who first came to prominence outside Chicago in Muddy Waters’ band and famously partnered with the  late, great harmonica player-vocalist Junior Wells, is constantly on tour, besides being at least nominal proprietor of a Chicago blues club (Legends). Led Zepplin, whose first hit “I Can’t Quit You Babe” was a cover of a song by Guy’s rival bluesman Otis Rush,  was cited by Kennedy Center chairman David M. Rubenstein as having “transformed the sound of rock ‘n’ roll with their lyricism and innovative song structures.” Oh yeah? Compared to the Jefferson Airplane, the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Rascals or the Grateful Dead? (As my dearest companion says, “When did Led Zepplin make an album titled American Beauty?“)

Guy himself holds the Brits in some esteem: “The guitar didn’t take you places until the British guys got a hold of it. That’s what opened the door for us,” he told Lonnae O’Neal Parker of the Washington Post. The door he’s talking about was to the bank. He and Wells made more moolah and reached far larger audiences as opening act for the Rolling Stones in the 1970s than they’d done before that on their own. But they were already stars of the blues circuit. Guy had appeared and recorded with Waters at the Newport Folk Festival, cut several memorable records under his own name for the Chess, Vanguard and Cobra labels, and collaborated with Wells on the notably restrained but eternally classic Hoodoo Man Blues (due to contracted obligations, he was listed in album credits as “Friendly Chap”).

Elements of his playing and stage antics, many of which were originated by Mississippi delta blues players, were evident in the playing and stage antics of Jimi Hendrix (who acknowledged his influence). The fact is that Guy, who came north from Louisiana in 1957, got his start in Chicago thanks in part to Theresa Needham, proprietress of the neighborhood tavern Theresa’,s and  long owned the South South Side club called the Checkerboard Lounge (which became a destination for many visiting rockers), was nonetheless considered by Chess producers as a stylistic outlier for his screaming, feedback-laced solos and long jams. Though he worked as a sideman for many of Chess’s mainstays, performed at the Fillmore West among other rock venues and toured Europe as part of the American Folk Blues Festival cavalcade  in 1965, he was simply not marketed strongly to young white rock-oriented audiences. Or if he was, those audiences were more dazzled by Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Keith Richards, Mick Fleetwood and the other guitar godz of the ’60s British Invasion.

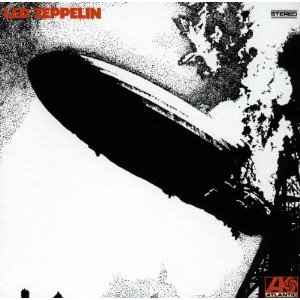

Led Zepplin, begun as an offshoot of the Yardbirds (which had featured Clapton, Page and Beck in close succession), had a smash debut with its eponymous first album, released in spring 1969. I distinctly recall  buying the LP at the Harvard Coop when it had just been released and was not yet known, during an Easter-weekend jaunt to Boston. I think I can claim to have introduced Led Zeppelin to my freshman dorm. By the end of the semester I was chagrined to have done so, as everyone seemed to have bought their own copy of the album, and it was a constantly repeated soundtrack for our room parties. Besides Page’s fast and furious, effects-laden guitar work, the band stood out for Robert Plant’s flamboyant, often high-pitched vocals and John Bonham’s hit-everything-hard drumming. In their first two albums, especially, Led Zeppelin lent a psychedelic patina to electric blues originated by a pantheon of mostly black Chicagoans (I don’t want to leave out Mike Bloomfield, Paul Butterfield and Elvin Bishop) who did not at the time dress in gypsy/hippy outfits or sport long, wavy hair.

buying the LP at the Harvard Coop when it had just been released and was not yet known, during an Easter-weekend jaunt to Boston. I think I can claim to have introduced Led Zeppelin to my freshman dorm. By the end of the semester I was chagrined to have done so, as everyone seemed to have bought their own copy of the album, and it was a constantly repeated soundtrack for our room parties. Besides Page’s fast and furious, effects-laden guitar work, the band stood out for Robert Plant’s flamboyant, often high-pitched vocals and John Bonham’s hit-everything-hard drumming. In their first two albums, especially, Led Zeppelin lent a psychedelic patina to electric blues originated by a pantheon of mostly black Chicagoans (I don’t want to leave out Mike Bloomfield, Paul Butterfield and Elvin Bishop) who did not at the time dress in gypsy/hippy outfits or sport long, wavy hair.

I wouldn’t challenge the Kennedy Center’s determination that Led Zeppelin changed rock, if it wasn’t that there are so many many many American-born and bred rockers, blues people, soul singers, songwriters and folkies who did as much or more (an I like Plant’s recent record Raising Sand with Alison Krause).  The inclusion of British rockers, or any foreign-born artists other than classical virtuosi, among Kennedy Center honorees began in 2004 with Elton John. (Elton John ????) and  continued in 2008 with Pete Townsend and Roger Daltry of the Who. They got their Awards before Springsteen, Merle Haggard, Dave Brubeck, Neil Diamond and Sonny Rollins received theirs. In 2010 it was Sir Paul McCartney.

Ok, Jerry Garcia is gone (Lesh, Hart, Kreutzman and Weir are out here, though). Grace Slick and  Paul Kantner might not be trusted to be politic in D.C., but if Marty Balin, Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady could be persuaded to join them . . . .well, that would be some reunion. John Sebastian lives a relatively modest but still active musical life near Woodstock. Felix Cavaliere is nowhere near as well known as he deserves to be. But if we’re going to give national awards to movers and shakers and mere entertainers in U.S. culture from the past 60 years, there’s a long list of potential recipients out of New Orleans (Allen Toussaint and Irma Thomas come immediately to mind), Memphis (Al Green, Sam Moore), Detroit (Berry Gordy might be appropriate, though Diana Ross and Smokey Robinson have already been cited, and could George Clinton be considered?),  L.A. (Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger standing up for the Doors), San Francisco (Carlos Sanatana would be a hip choice), Boston (Gary Burton, who after all was at the early junction of jazz, country music and rock and contributed mightily to Berklee College of Music for decades) — and Nashville, Miami, Atlanta, Seattle, Austin, many other American cities and country communities — who deserve the attention and semi-governmental stamp of approval. A good case could be made for John Fogerty, Electric Flo and Eddie (the Turtles), Gamble and Huff, Holly Near, Bernice Reagon, Johnny Pacheco, Larry Harlow, Ruben Blades, Tony Trischka and d0zens of others.

According to Wikipedia,

Each year the Kennedy Center’s national artists committee and past honorees present recommendations for proposed Honorees to the Board of Trustees of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[10] The selection process is kept secret . . .

Secret, schmecret. I’m not even venturing to suggest deeply deserving, enduringly creative but non-pop American musical artists. Given the bounty of American pop-rock-soul-salsa (the lone Kennedy Center honor for any Hispanic American went to Chita Rivera) exemplars, and the little matter than the UK does not reciprocate by officially honoring the artistry of our gang, can the trend to give Kennedy Center Awards to the British Invaders be nipped in the bud?