Guitarist John McLaughlin‘s Mahavishnu Orchestra was the highest-flying of any ensemble emerging from Miles Davis’ jazz-rock initiative in the early 1970s, establishing a previously unapproached standard of virtuosity, improvisational excitement and commercial success for all-instrumental electric bands to follow. Drummer G. Calvin Weston‘s Treasures of the Spirit quintet playing music of McLaughlin’s MO at the 92nd St. Y Tribeca in NYC last night (Feb 10, 2012) heroically addressed the complexity, speed and power of unique, difficult, enduring and compelling repertoire – a feat rarely attempted but inspiring to hear when musicians nail it, as Weston’s cohorts did.

With electric guitar Bill Berends, violinist Marina Vishnyakova, electric bassist Elliot Garland and keyboardist David Dzubinski addressing roles originally performed by McLaughlin himself (usually on a double-necked instrument), Jerry Goodman (still active, he’s been in the Dixie Dregs among other genre-confounding groups), Rick Laird (now Richard Laird, photographer) and Jan Hammer (composer for “Miami Vice,” Cocaine Cowboys, innovative computer animations and the first commercial tv network in Eastern Europe), Weston pounded out gloriously fast, muscularly emphatic rhythms to propel “Hope,” “One Word,” “The Dance of Maya,” “Open Country Joy”, “Triology,” “Dawn” and “Meeting of the Spirits” — multi-part compositions originally recorded on The Inner Mounting Flame (released in 1971), Birds of Fire (’72) and The Lost Trident Sessions (recorded in ’73, not released until 1999).  If it seems odd for a drummer to reprise material written for a frontline of electric guitar, violin and keyboards (including synth) plus electric bass, know that the original Mahavishnu Orchestra was driven by Billy Cobham, a contributor as essential to the group’s sound and prodigious four-year-run (reportedly 580 concerts during that period) as McLaughlin himself. (In fact, drummer Gregg Bendian also has an ambitious Mahavishnu Project -Redefined , which coincidentally had a booking scheduled for tonight (Feb 11) in New Hope, PA — postponed due to icy roads in the region).

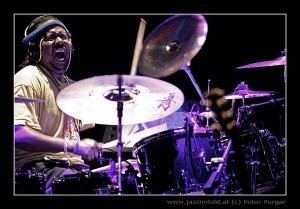

Obviously Weston digs Cobham. He showed up in Tribeca with a vast array of tom-toms, cymbals, a gong and double bass drums, akin to the kit Cobham eventually employed. Weston’s beats were true to Cobham’s models: solidly struck, whip-snap fast and precisely fulfilling the unconventional time signatures derived from Indian tabla practices which gave the Mahavishnu Orchestra its distinctive motivation. But Weston has his own shtick, too. Among his skills:

- ferocious press rolls on his snare, but also with his two feet on the kick pedals;

- Â independence yet also paired coordination of his four limbs;

- ability to throw in fills and accents where there wouldn’t seem to be time to put them;

- mastery of the different pitches/timbres of all those cymbals and toms;

- control of dynamics so that there’s always a notch up-the-scale to go,

- and with bassist Garland an instinct for bringing the lowdown funk out of Mahavishnu material initially intended for seeking a transcendent spiritual plane.

Weston directed all the action from his seat in the manner of drummer-bandleaders like Art Blakey and Jack DeJohnette. At 52, he has enviable reserves of energy. He turned what had been advertised as two sets into one long one, throwing punches for two hours continuously like a determined boxer who doesn’t hear the bell tolling that he can rest between rounds.

Although the Mahavishnu Orchestra was brilliantly conceived to flow from classically-stated themes to raging collective jams, soft, folkish or raga-like passages to competitive call-and-response episodes, it was the bodacious end of its sonic spectrum that most engaged listeners in the ’70s and has wowed us ever since. Not that the MO was just loud, though it was indeed loud. The MO was on fire, with neatly shorn, pale, earnest, white-clad young McLaughlin, a disciple of Sri Chinmoy (who gave him the name “Mahavishnu” after the Hindu creator/destroyer/preserver of the universe) at its center, engaged yet serene. He excelled at articulating strange scalar lines and bent notes in upper octaves at speed-metal tempi, while violinist Goodman bowed quickly also in top registers and Hammer bent or pushed pitches where newly developed synthesizers had never gone before.

Berends, Vishnyakova and Dzubinski worked the same angles to nearly the same affect. There were minor, easily forgiven fluctuations of intonation, and by definition they weren’t the originators of the MO vision, so the question sometimes arose: Whose music is this? Weston’s Treasures of the Spirit last night was not so visually imposing as its predecessor: The players wore street clothes, and Berends bears a resemblance to Penn Gillette wearing a pirate bandana, rather than McLaughlin the handsome Yorkshireman pure as snow aspiring to eternal bliss.

Well, it’s no longer 1971, and the shock of hearing musicians reach with hedonistic rock fervor for the holy unattainable is gone for good. The small crowd at the Y, a multi-use facility with excellent performance space but off the nightlife track, seemed to be predominantly men who remember hearing Mahavishnu in their youth and have not gotten over it (like me). That’s unfortunate, because this music — not just its imagery and mythology — Â as Weston & Co. put it forth should appeal to ravers of all ages, anyone looking to pump it up.

G. Calvin Weston’s other associations are certifiably hip: He’s recorded and toured with Ornette Coleman’s amplified double quartet Prime Time, been in the Lounge Lizards, the Free Form Funky Freqs with Vernon Reid and Jamaaladeen Tacuma and on the Get Shorty soundtrack. In each context he strives for the personal satisfaction of making music live, immediate and interactive as possible.

If Treasures of the Spirit has a flaw, it’s that the band sometimes moves less than persuasively through the pastoral, contemplative moments McLaughlin planted in his pieces for introduction, punctuation and contrast to the urgency Weston wants to convey about time passing inexorably, now. Time is moving fast, there’s no way to stop it and we don’t exactly catch up by reaching back 40 years to remembered pleasures. But revisiting, restoring and reviving music that was born years ago but has lost no vitality doesn’t feel like a desperate attempt to recapture an era so much as a statement of faith in the value of that music then and in the present. Jazz — fusion-manifestations included — is made in the moment and if the sounds fit those who play it and hear it, they are indeed treasures of the spirit. I came home from G. Calvin Weston’s show enriched by people out here collaboratively lifting earthy rhythms and searing melodies to the open sky.