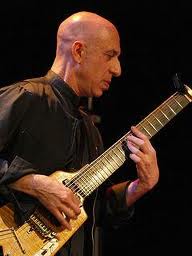

No label exists for the music of composer-guitarist-saxophonist Elliott Sharp, who performed with two of his Carbon concept ensembles at Roulette in Brooklyn last week. In both quartet (Sharp on 8-string guitarbass with electronic processing, curved soprano and tenor saxes, and musicians playing electric bass, prepared harp and drums) and septet (the quartet plus second electric bassist, pianist and percussionist) formations, vernacular rock rhythms anchored advanced explorations of texture and gesture. Repetition of brief motives slid upon and beneath shifting sonic fields. Narrative arc encompassed extended and advanced instrumental techniques.

Sharp is a veteran in high standing of the late ’70s and thereafter downtown New York community of originalists, a status he substantiates by pursuing his own investigations of how sounds synchronize, collide and collude. His pieces, presented in fairly short versions (10 minutes? I wasn’t clocking) he alluded to wryly as “songs”, are derived from patterns found in nature, science and math, but his interests are in raw roars and tribalism. He’s not afraid of dissonance, indeed, it is for him what B’rer Rabbit called “the briar patch.” As sophisticated as is Sharp’s mastery of the mysteries that can be unfolded by so-called minimalism, the enveloping storm he stirs up dashes all bounds.

There are many ways to approach and perceive Sharp’s work. His music has volume levels (often, not always) and surface grooves that will please headbangers, but also complex layers of more subtly intriguing sounds and ideas. And Sharp is conscious of it all. He’s quite a good blues guitarist, for one thing (having drawn the late Hubert Sumlin, Howlin’ Wolf‘s right-hand man, into collaborations in his Terraplane band), and you see that from the way he strums and picks his broad-necked guitarbass, no matter what chords or clusters he’s getting from it. But he also is doing unusual work with overtones that he produces via a tapping technique, all the fingers of both hands on the guitar’s neck. If that’s coming from the blues, it’s rather a distance from the genre’s roots.

At Roulette, he offered only a couple of “melodies” in any conventional sense, though melody could be thought of as arising from his efforts (and in the quartet set bassist Marc Sloan put forth melodic figures, intermittently. That was interesting, too: Sloan did not keep a constant bass line going, instead playing a phrase, waiting, playing another phrase, etc., and at one point using a metal bar as a bow across his ax’s body, while drummer Joseph Trump provided the solid beat a la a loose, less frenetic Keith Moon). On his curved soprano, Sharp used continuous (circular) breathing, requiring serious concentration, and repeated a hyper-fast fingering pattern to produce the kind of full-out, throaty wail I associate with the Master Musicians of Jajouka all blowing double-reed rhaitas. Sharp also moves a lot of wind with his tenor — it has the squawk of an r&b honker, but he’s going less for tuneful, however-overblown riffs than a blur of unremitting sound. The other musicians improvise, but not jazzily. The emphasis is on collective.

So, within or from all this the effect is orchestral. There is much more going on than four people usually generate — especially considering that three of his four play “strings,” reconstructed. During the second septet (Orchestra Carbon) half of his Roulette “CARBONic Evening”, Sharp conducted some big blocky section changes, though again the instruments were layered like tectonic plates, creating new interrelationships and densities as they slipped under and over each other. At times this evoked an earthquake, breaking a crusty topside into shards yet sustaining characteristics of a given plot. In one movement, pianist Jenny Lin swept her keyboard and harpist Shelley Burgon did the same for glisses that seemed to fling open simultaneously all the doors and windows of a house in a cyclone. In a finale, which Sharp introduced as “dreaded” by his musicians, the action was all low register, earth rumbling under ocean currents. One thick stew of an ocean . . .

Sharp’s music can certainly seem foreboding, maybe anarchic or confrontational, and I bet my descriptions don’t do anything to belie that impression. But he is not nihilistic or even morbidly dark. The music he makes is ultra-deliberate, however wild it seems on first exposure, and he has labored to develop virtuosity in spheres lesser musicians only pretend to acknowledge actually exist.

I find the music he makes risky. His concerts aren’t inevitably successful; his stuff is not easy to play (I didn’t already mention that in Orchestra Carbon percussionist Danny Tunick did wonders on vibes, with a basic 4/4 groove that once in a while added added a 5/4 measure; second bassist Russ Flynn looked startled when called on to “solo” but held his own). It’s not generically easy listening, either. But it’s very rewarding, bracing and inspiring, primal and technological, monstrous yet humane.

Elliott Sharp has released some 85 albums. If I were to suggest one for starters, it might be Sharp? Monk? Sharp! Monk! because it’s a solo album that generously displays his guitarism and interpretive insights while dealing with the legacy of a canonical figure he reveres and who exemplifies the notion of “ugly beauty” from which E# does not shy.

But then you’d not be hearing Sharp’s self-designed and -realized launching points, which ain’t like Monk’s (or only like Monk’s). So I don’t know what I’d recommend. Oh, yeah: I recommend you hear him live.

Alternatively, here’s a trailer for a documentary film on Elliott Sharp. Maybe it shows better than I tell what the man and his music are about.