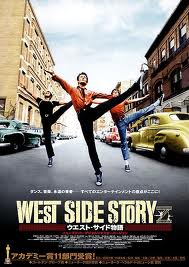

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of West Side Story — the movie, released October 18 1961,  Â not the play which debuted on Broadway in 1957 — for my column in CityArts – New York, I listened to the Bernstein/Sondheim music in many variations. Here’s my report, slightly revised for the web:

not the play which debuted on Broadway in 1957 — for my column in CityArts – New York, I listened to the Bernstein/Sondheim music in many variations. Here’s my report, slightly revised for the web:

For West Side Story, the score’s the thing. Even first exposure to either the 1957 original Broadway cast album or the 1961 Academy Award-winning movie soundtrack reveals this music to be the peak of the golden, pre-rock age of American song.

Leonard Bernstein’s melodies are immediately catchy and unforgettable, yet on further listening ever more complex and interconnected. Stephen Sondheim’s hard, sharp, wry yet also open-hearted lyrics are the perfect match. The story’s drama – love denied, a la Shakespeare — gains emotion and context from the indissoluble fusion of words and tunes. Dance, thanks to daring Jerome Robbins, springs from and reiterates the songs’ jagged, jazzy rhythms.

Characters are defined by their tunes, moods are crystalized, incidents foretold. The effect is immediate and modern, though today we recognize the sounds as from a distant time, another place. There’s no big beat, ear candy or overt production. People sing without winking about how people in real life don’t sing.

But remember – or imagine — leaving Broadway’s Winter Garden in ’57 or a movie palace anywhere in ’61, melodies and snatches of lyrics from “The Jet Song,” “Something’s Coming,” “Maria,” “Tonight,” “America,” “Cool,” “I Feel Pretty,” “Somewhere,” “Gee, Officer Krumpke,” “A Boy Like That” resounding with the noise and speech of the street. Such tense, tough, vernacular compressions of narrative were new onstage and screen. The prologue remains one of the most dramatic 8-minute sequences of film-with-music I know.

Frankness in song was familiar in the blues, cloaked in rhythm ‘n’ blues, circled in rockabilly and countrypolitan, alluded to by Sinatra and had some precedence in earlier musicals including Showboat, South Pacific, Pal Joey and Guys and Dolls. But the barely repressed angst of West Side Story and its sudden flare-ups into murderous violence were the stuff half a century ago of opera, not Broadway or Hollywood (much less television).

Though just a kid then and a clumsy one at that, I recall being inspired by the pent-up energy of Bernstein’s instrumental prologue set in the gang-dominated playground to try to float while walking like finger-snapping Russ “Riff” Tamblyn. My brothers and friends and I acted out the tragic role of Tony, all innocent expectation, raising voice with syncopated emphasis, “I don’t know/What it is/But it is/Coming my way.” We hissed like a Jet, “Boy, boy, crazy boy, play it cool, boy,” though we might not have understood the truth of mob-appeal captured in Sondheim’s couplet “Little boy, you’re a man/Little man, you’re a king.”

We tried out incongruous flamenco moves in imitation of the sharp-suited Sharks and took on the tongue-rolling accent of Anita satirizing “Amer-EEE-kah.” We might even drape ourselves in flimsy drag and prance around asking, “Who’s that pretty girl in the mirror, there?/Who can that attractive girl be? Such a pretty face/Such a pretty dress/such a pretty smile/Such a pretty me!”

We tried out incongruous flamenco moves in imitation of the sharp-suited Sharks and took on the tongue-rolling accent of Anita satirizing “Amer-EEE-kah.” We might even drape ourselves in flimsy drag and prance around asking, “Who’s that pretty girl in the mirror, there?/Who can that attractive girl be? Such a pretty face/Such a pretty dress/such a pretty smile/Such a pretty me!”

The sheer lyricism Bernstein tapped for the love songs “Maria” and “Tonight” were impossible for us kids to spoof, and since them we’ve rarely encountered such outright idealism regarding romance (compare “Maria” to “Wild Thing,” “Tonight” to “Tonight’s Gonna Be A Good Night“). The movie’s purely instrumental episodes – the playground prologue, the dance in the gym, the rumble under the highway – were electrically exciting, and remain so in the “Symphonic Dances” Bernstein forged from them for concert performance. Yet his dissonant intervals, slashing interjections, driving counterpoint, and luminous, deceptively simple lines have generally resisted others’ interpretations. The jazz versions by Oscar Peterson, the Dave Brubeck Quartet (especially saxophonist Paul Desmond’s contribution), Stan Kenton, Sarah Vaughan, Andre Previn, Dave Gruisin and Buddy Rich all add their various frissons of personality to the originals, but aren’t necessarily improvements. (The Manhattan School of Music Jazz Orchestra, conducted by Justin DiCioccio, performs arrangements from Kenton’s, Rich’s and Grusin’s renditions on Friday Nov. 11 at the school’s Borden Auditorium, and Monday Nov. 21 at Dizzy’s Club, Jazz at Lincoln Center).

I think the West Side Story score does have a couple flaws, both in its love story’s culmination and resolution. Neither “One Hand, One Heart” nor “Somewhere” heal the Jets-Sharks feud or master the work’s underlying themes of miscegenation and assimilation. I may be a tough old nut now, but I’ve never been much moved by those pieces in the movie, either (maybe ’cause I find Natalie Wood and Richard Beymer completely unbelievable as lovers

I think the West Side Story score does have a couple flaws, both in its love story’s culmination and resolution. Neither “One Hand, One Heart” nor “Somewhere” heal the Jets-Sharks feud or master the work’s underlying themes of miscegenation and assimilation. I may be a tough old nut now, but I’ve never been much moved by those pieces in the movie, either (maybe ’cause I find Natalie Wood and Richard Beymer completely unbelievable as lovers ).

).

But all these songs, from their moment of emergence, have made undeniable claims on our consciousness. When America heard West Side Story, the play’s way of expressing conflict, anticipation, romantic awe, flirtation, sarcasm, bravado and hope became our own. Which is why more than 50 years after debuting, it is continuously revisited in high school and community productions, in ads and jingles, as shorthand for states of being. And why when Arthur Laurents, who wrote the book of the musical, diirected a 2009 revival of West Side Story with dialog and singing in Spanish, aiming for more pointed energy and less compromised characterizations, the knee-jerk response was Yes!

The sentiments of West Side Story’s music reflected or became basic American vocabulary. There’s not much like it anymore, but this music is with us still.