Christopher Buckley’s New York Times Book Review frontpage piece on And So It Goes, Charles J. Shields’ biography of Kurt Vonnegut, is as lazy a bit of evaluation as it’s possible to pick up a paycheck for. I can’t tell from it anything about Shields’ book, and nothing about Vonnegut’s many novels, either. (See “jazz” content at post’s end).

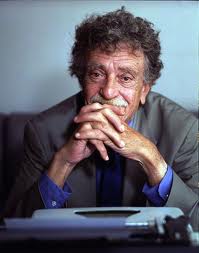

How does Buckley — whose comic novels I’ve enjoyed (esp. his first, The White House Mess) – – spend his 1500 words about a 500-page life of one of America’s best-selling fabulists of the late 20th century? He entertains us with what interests him. So we  learn in the lede  that the bio is “often hearthbreaking,” evidently because of Vonnegut’s human flaws, his “vexed” relations with women (such as the “hell on earth” — Buckley’s phrase — he shared in marriage with photographer Jill Krementz) and his attempt at suicide, perhaps in imitation of his mother (whose did indeed kill herself). We learn, too, that Vonnegut was sad, angry about the ways of the world (what satirist isn’t?) and resented being underrated by the literary elite but got rich off of actual book sales (sounds like a fair enough trade-off). We don’t find out what author Shields himself says about any of this in his long volume.

Berkeley neither tells nor shows us how Shields writes, explains why Vonnegut was read (and feted and influential) or describes the social context of the period of his greatest productivity. I hope Shields writes about that; as a reader, I’m  interested in an era that resulted in mainstream publication and public embrace of American satires and other serious, experimental, speculative, entertaining fictions by V., his pal Joseph Heller and also Pyncheon, Roth, Nabokov, Mailer, Coover, Burroughs, Brautigan, Algren, Phillip Dick, Hunter Thompson, Thomas Berger, Jerzy Kozinsky, Jerome Charyn, Ursula LeGuin, Grace Paley, Stanley Elkin, John Barth, Gore Vidal, Terry Southern, Donald Barthelme, Ishmael Reed, Chester Himes, James Purdy, Bruce Jay Friedman, Richard Condon, Tom Wolfe, arguably even such learned pundits as William F. Buckley, Jr.

It is this latter’s son, the reviewer Chris, who gets stuck on whether Kurt Vonnegut will matter forevermore (but doesn’t tell us if he thinks he should, only ties him to J.D. Salinger, relatively speaking a realist). One can only surmise Shields wrote a 500+page book because he thought his subject mattered.

I dig Vonnegut, having read most of his 14 novels from the dystopian Player Piano (1952, much indebted to Orwell and Huxley) through Timequake (1997), and I recommend the half dozen best of them highly.Vonnegut wrote clearly and directly, with a Midwestern-born sense of economy and understatement. He was comic and imaginative in a plainspoken style with an undercurrent of feeling — which might seem simple, but isn’t. Try to imitate his voice, his scruples about showing the worst sides of some protagonists and yet his compassion for ordinariness, his dry flights of fancy. In  Sirens of Titan (1959) and Cat’s Cradle (1963)

Sirens of Titan (1959) and Cat’s Cradle (1963)  he is hilariously ironic and unblinkingly pessimistic, deeply fatalistic and soaringly fantastical. I get continued pleasure from both those novels.

he is hilariously ironic and unblinkingly pessimistic, deeply fatalistic and soaringly fantastical. I get continued pleasure from both those novels.

Mother Night I haven’t read for quite a while but recall for its daringly dark yet sympathetic character creation. God Bless You Mr. Rosewater also sticks in my mind as an unpredictable story about mixed-up morality.

Personally I find Slaughterhouse Five more sentimental and obvious than any of these early works, but I guess to many readers it seems most heart-felt, and it is no doubt earnest — the fire-bombing of Dresden is a searing episode. Of V’s later works, I thought Breakfast of Champions troubling, skipped Slapstick, remember little of Jailbird and avoided Deadeye Dick. Galapagos was diverting, Bluebeard mystifying and Hocus Pocus not very memorable, but I am firmly in favor of Timequake. To me Vonnegut’s summing up joins Heller’s Portrait of an Artist, As an Old Man and Charles Bukowski’s Pulp as the finest, funniest recapitulations of careers writing fiction I’ve read.

I’ve met Vonnegut’s daughter Edie, and like her paintings of Domestic Goddesses, Â and once met the man himself. I was standing behind him in a line for food after a preview showing of Robert Altman’s Kansas City. I introduced myself as a fan, and answered his question about what I do as “write about jazz.” Vonnegut, whom I remember looking sort of hang-dog, said he had played clarinet, and loved jazz. He added that he had tried to introduce the music to high school students while he was teaching at a high school in Cape Cod, but couldn’t get them interested.

I said I knew of only one bit of writing about music in his novels, one of my favorite scenes: When space traveller Malachi Constant finds himself stuck for an indeterminable amount of time in the caves of Mercury, he takes solace from the beautiful songs, light patterns and messages (“I am here, I am here, I am here” and “So glad you are, so glad you are, so glad you are”) of the harmoniums. Vonnegut seemed pleased I could quote that.

I haven’t read Shields’ bio, and might not, but it and Kurt Vonnegut, too, deserve better from the Times than being tossed off as topics rather beneath the reviewer’s engagement.