Attempts to revisit the music of an extraordinary improviser work all too infrequently, if “work” means evoking something close to the living presence of the player him-or-herself. This is true even when the tribute-payers are the tributee’s collaborators, bearing the best intentions.

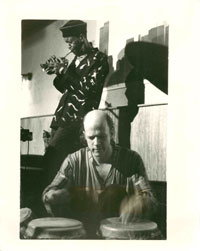

But “In the Spirit of Don Cherry,” an all-star octet organized by pianist Karl Berger was able at a Symphony Space performance a couple weeks back to imbue seldom-heard yet unusually memorable songs with the wit, grace and world-ranging musicality of the man who created them (playing pocket trumpet with Collin Walcott, tabla in this photo by Lona Foote).

Don Cherry and Colin Walcott – photo ©Lona Foote

Berger,  the force behind the legendary, influential and under-reported Creative Music Studio of Woodstock — with trumpeter/cornetist Graham Haynes, tenor saxophonist Peter Apfelbaum, tubaist Bob Stewart, guitarist Kenny Wessel, bassist Mark Helias, drummer Tani Tabal and vocalist Ingrid Sertso — performed tunes Cherry included in his great albums of suites Complete Communion and Symphony for Improvisers (both on celebrated Blue Note Records, from 1965 and ’66, respectively) as well as a couple recorded elsewhere, like “Art Deco,” title track of a 1986 album. True to its name, the concert’s operative plan was “in the spirit of . . .” rather than “note-for-note.” The musicians, most of whom had worked directly with Cherry, evoked the beauty, playfulness, pathos, imagination, unforced complexity and constant interactivity he tapped in himself and others by blowing as if they were onstage with him.

I have written about Cherry before, based on several personal encounters. He is probably best known for his collaborations with such indelibly jazz-linked individualists as Ornette Coleman, Sonny Rollins, Albert Ayler, George Russell, Archie Shepp and John Coltrane — his bits on albums by rockers Lou Reed, Ian Drury, Steve Hillage and Yoko Ono — his close work with drummer Edward Blackwell, electronics composer Jon Appleton, and the indigenous-world-jazz trio Codona — his large ensemble efforts with the Jazz Composers Orchestra, the Haden-Bley Liberation Music Orchestra, Sun Ra and Krzysztof Penderecki. None of them ever overwhelmed him; they depended upon his unique ability to compliment by being distinctly himself. He urged that same empathy in musicians as diversely based as Gato Barbieri, Bobo Stenson, Okay Temiz and Pharoah Sanders.

Cherry’s playing was rooted in melody and rhythm’s dance; he was fascinated with sounds be they organic, acoustic, amplified and/or processed, and into everything from trad to bop to avant garde, bossa nova to gamelan to raga to punk to noise. It speaks volumes that his ability to inspire others was one of his strong suits, and it’s remarkable that so much of his voice, concept, ok spirit, survives 13 years after his death. The musicians who admire what he did are those who keep him alive, of course, and Berger’s crew did an exemplary job of tossing riffs back and forth, expanding on their unforeseen implications, finding backdrops to underscore each other’s solo, making directly personal statements that blended into the ensemble whole, coloring with intensity, summoning deep and shifting moods but staying buoyant, always buoyant.

Those are the very attributes of Communion, which Cherry recorded with a quartet (Barbieri, tenor sax; Henry Grimes, bass; Blackwell, drums) that seems as busy as a band twice as big, and Symphony, (Barbieri, Grimes and Blackwell with Berger on vibes as well as piano, J.F. Jenny Clarke playing second bass, and Pharoah Sanders playing an amazing piccolo part) that seems transparent, for all the collective improvisation in which its personnel reveled.

Especially nice little touches from the band Berger assembled (which has performed in Europe and would like to convene again; it’s an project with shifting personnel) included: his own “arranger’s piano” not meant to impress but to serve; Wessel’s guitar swings from country twang to digital effects; Helias’ hardwood tone and clear, fast figures; Stewart’s tirelessly upbeat oom-pah; Haynes’ determination to play what he hadn’t pre-planned; Apfelbaum’s security with the material and willingness to wrestle with it; Ingrid’s warmth and quietly fitting lyrics, Tabal’s seamless beat. The program was varied and fresh, with unexpected interpretations (“Manhattan Cry” stripped down from a roar, as it was recorded, to its ballad essence) and sudden switchups like one of Cherry’s unruly quirky lines delivered by the ensemble quick as a wink with nary a stumble.

I miss Don Cherry and wish there was a biography of him, because he was a fascinating characgter. He was part Choctaw Indian from Oklahoma, and from an early age loved the trumpet playing of Clifford Brown. He was drawn to fabrics and textiles, using tapestries by his Swedish wife, Moki, for stage dressing or his own clothes whenever he could. I’ve heard stories of him roller-skating around Los Angeles in the ’50s, of him spelunking into sacred Native American caves to play clay ocarinas, of how appeared daily under the cell windows of Angela Davis to serenade her on wood flutes during one of her incarcerations. In the early ’70s he held two weeks of concerts in a geodesic dome in the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark and in the ’90s, not in the best of shape, he dropped into East Village dives to play with all comers. He is survived by musical children, including keyboardist David Ornette Cherry, his step-daughter Neneh Cherry and youngest son, Eagle-Eye.

ESP Disks has released three volumes of Don Cherry’s band with Barbieri and Berger live at Montmarte, 1966 — they’re preparing the repertoire for Symphony for Improvisers, rough but eager get it right. These recordings, and the vast majority of his others — with Old and New Dreams, with Johnny Dynani, with the Mandingo Griot Society, Trilok Gurtu with Tamma — are enduring gifts.

Berger recalled Cherry between songs with both awe and rue. The musicians, together, reveled in what he’d wrought. The audience comprised musicians and aficionados who knew him and were slow to leave the hall after the gig because his sound had been conjured. Maybe Don Cherry’s ghost was about. I don’t often think that, but this time I did.

Subscribe by Email

Subscribe by RSS

howardmandel.com

All JBJ posts