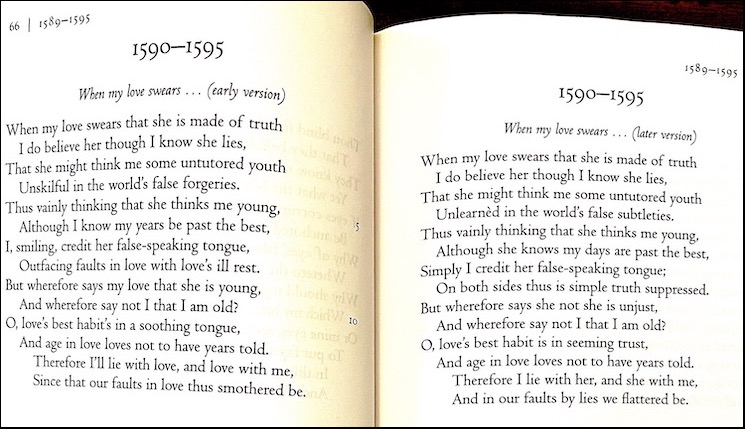

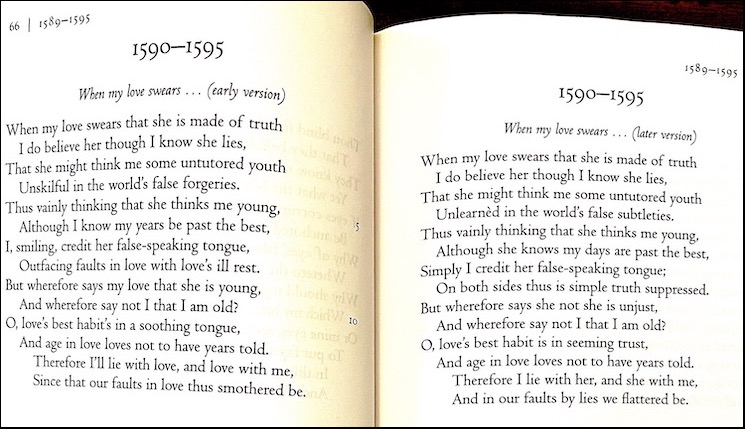

Which do you prefer? The earlier or the later version?

Excerpted from All the Sonnets of Shakespeare edited by Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells.

Cambridge University Press, 2020

I prefer the later version.

Arts, Media & Culture News with 'tude

by Jan Herman

Which do you prefer? The earlier or the later version?

I prefer the later version.

an ArtsJournal blog

I know only the second version, and it has long been one of my favorites. If it had never been revised, I’m sure I would have been fond of the first version too. But when you see them side-by-side, it is easy to see the “improvements” that were made, from the obvious double negative of “false forgeries” to the numerous more subtle ones. Thanks for sharing this!

Thnx for yr comment. Yes, the “improvements” give the sonnet a somewhat different meaning and from a different point of view. I leave it to the reader to say what the differences are.

I also knew only the revised version – and have always thought it remarkably wise (just edging into bitterness or cynicism — “love’s best habit is in seeming trust”). Reading the former, one now sees the lyrical improvements but also the sharper edge: “And in our faults by lies we flattered be.”

Yes to the former (original?) version.

The later is a fine moral clarion call (sermon of sorts); whereas the original is poetry.

My two cents!

Bob

Courtesy of my indefatigable staff of thousands, here is Chateaubriand commenting in “Memoirs from Beyond the Grave” (1848-50) on Shakespeare and another relevant sonnet:

“Shakespeare would have had a great number of lovers if we reckoned them one per sonnet. The creator of Desdemona and Juliet grew old without losing his taste for love. Was the unnamed woman addressed in such charming verse proud or happy to be the object of Shakespeare’s sonnets? One might doubt it, for an old man’s fame is like an old woman’s diamonds: they may adorn her, but they cannot make her pretty.” The tragic Englishman wrote his mistress:

No longer mourn for me when I am dead:

Then you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world, with vilest worms to dwell:

Nay, if you read this line, remember not

The hand that writ it; for I love you so,

That I in vour sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O, if, I say, you look upon this verse,

When I, perhaps, compounded am with clay;

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse,

But let your love ever with my life decay;

Lest the wise world should look into your moan,

And mock you with me after I am gone.

The first draft reads like Shakespeare was not yet sure what his poem was about.

In line four he initially goes for superficially pleasing alliteration that happens to repeat the idea of ‘lies’ from the first couplet without really adding anything to it (‘false forgeries’). Upon reflection, he realized that his subject is not calculated lying but rather the rationalizations we invent when our intellect attempts to interfere with our emotions–‘false subtleties.’ (He could have just as easily changed it to “subtle forgeries’ and retained the echo of ‘lies’ but that would not have scanned properly.)

“Simply’ in line 7 is an obvious evasion of this complex rationalization, besides fitting the music of the poem better than ‘I, smiling,”–he is also trying here to assume a youthful frankness and naivete that he knows is no longer really possible in one whose ‘days are past the best.’ Likewise, ‘unskillful’ was changed to ‘unlearned’ in line 4 because such artful self-deception is something on acquires with maturity, out of necessity, and not a skill one can or needs to possess in youth. This self-deceptin is reinforced by the reference to ‘simple truth suppressed’ in line 8–the original line 8 is almost indecipherable, and was probably never more than a placeholder. until Shakespeare thought of something better. The replacement of ‘young’ with ‘unjust’ tightens the conceit started in the octet and removes the only reference to the mistress’s age (all other such references are to HIS age). ‘Soothing tongue’ becomes ‘seeming trust’ not only to fit the new rhyme, but also because of the relationship between the words ‘trust’ and ‘truth.’

Finally, Shakespeare removes the word ‘love’ completely from the final couplet, when in the first draft it had appeared thrice, amplifying the rude pun on ‘lie’ (replacing ‘smothered’ with ‘flattered’ also increases the sense of mutual self-deception) and reducing Love to the selfish act of sex. This may be what an an earlier commenter had in mind when he claimed that the first draft had more poetry in it.

Well-reasoned if a tiny bit sharp-edged. But no matter…….. Personally (naturally) I prefer a bit of blur, painterliness, sfumato etc. to the art I cherish. That said your response was well-reasoned and thorough-going. As an aside, I suppose you are aware that Shakespeare wore an ear-ring. I wonder what that meant in his day and age?

Thanks again and my very best wishes to you and yours.

Bob