“It’s a late winter’s afternoon on the top of Cross Hill, with Hardcastle Crags on one side and Colden Valley on the other. Down in their depth of hibernating trees and gritstone slabs, darkness isn’t coming down — it’s rising like a cold damp tide.”

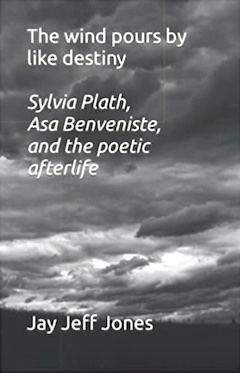

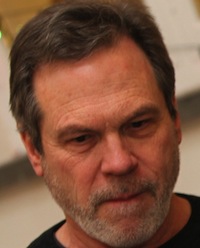

So begins Jay Jeff Jones’s new chapbook, The wind pours by like destiny, an uncommonly rich meditation on the poets Sylvia Plath and Asa Benveniste and, as the subtitle puts it, “the poetic afterlife.” Evocative prose lets us know we’re in for an illuminating read.

The chapbook also arrives nicely timed to an upcoming celebration marking Plath’s 90th birthday with an international gathering of writers, poets, and scholars in Heptonstall, the West Yorkshire village where she is buried.

Jones, who lives in the village, is no romantic idolator but an American expat playwright, journalist, and critic, who happens to be a poet himself with a deeply probing regard for literary history.

Plath, he points out, “came to prominence, in both life and death, during a time when poets were still a literary elite, when some of them could turn into minor media stars and, in the spirit of Percy Bysshe Shelley, and William Blake, act as provocateurs of cultural revolution.”

Referencing the Beat poets of her time, he notes that the most confident of them “could thrill large audiences, confront the establishment and develop decadent lustres almost like their jazz bop collaborators and, later, sycophantic rock and roll friends.

“Plath never did any of that but, while many poets of that generation have faded from public awareness, her flame burns brighter than ever.”

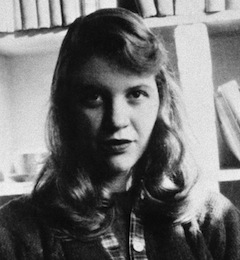

Confidence did not come easily to Plath — far from it, as evidenced in the diaries she kept and by the depression that led to her suicide at the age of 31. Moreover, the landscape of the Heptonstall environs, where she briefly and reluctantly lived during her marriage to the poet Ted Hughes before they moved to Devon, compounded her depression. These lines from her poem “Hardcastle Craigs” testify to that:

The long wind, paring her person down

To a pinch of flame, blew its burdened whistle

In the whorl of her ear,

And like a scooped-out pumpkin crown

Her head cupped the babel.

The whole landscape

Loomed absolute as the antique world was

Once, in its earliest sway of lymph and sap,

Unaltered by eyes,

Enough to snuff the quick

Of her small heat out, but before the weight

Of stones and hills of stones could break

Her down to mere quartz grit in that stony light,

She turned back.

With a vividness matching Plath’s, Jones writes:

The uplands are a stonewalled pattern of vacant fields and meadows, and the faraway moors look grey and barren. From the red tension on the horizon comes not warmth but a wind hardened on the edges of Atlantic storm waves. This is the natural landscape for tough history, for subsistence hill farming, cradle-to-grave mill working, adversity waiting around every corner and a whole lot of outlawry.

“From here, it’s a short walk to Heptonstall, a village of medieval origin with two churches, one chapel and three graveyards. In the oldest of these, the bone strata measure out centuries, with periods crowded into short lives taken by plague and consumption. At times, they could have tied the dead bell to a metronome. If she had been asked, [Plath] was unlikely to have chosen this village as her final resting place.”

The gravesite has since become a destination for all sorts of fans, not least Patti Smith, who told an interviewer she visited it three times. The first time, all she wanted was a photograph. “I took beautiful photographs. The photographs somehow were lost. So I went again to take another photograph. It snowed. The photographs were terrible. I couldn’t leave I was so paralyzed. It wasn’t until the third time that I visited as a loving friend. Just sat quietly.”

It would be hard to improve upon Smith’s description of Plath as having “the incisive observational powers of a female surgeon cutting out her own heart.”

Jones, for his part, characterizes Plath’s poetry as “a language of spells — the creation of which relies on passion, instinct, and chance.” And he chides “those who in the Calvinist desiccating vocabulary of Theory-speak, lithe and nuanced as a coroner’s report, conscript Plath’s writing as testament for a certain, cold-blooded Feminism.”

With apt digressions about the so-called confessional poets of mid-20th-century America, namely Robert Lowell, John Berryman, and, most significantly, Anne Sexton, Jones also claims that if Plath had lived longer she might well have “disowned Confessionalism” too.

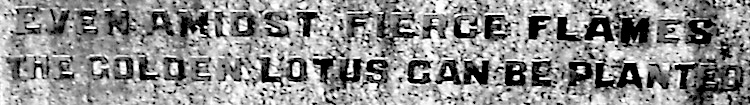

This meditation, enriched by the author’s familiarity with the village and its medieval history, ultimately points to the ticking clock of Plath’s life as an obsession for fans who may confuse a grave with a portal, as though it were “a looking-glass mirage, through which the living can contact the absent idol.” Her headstone bearing an epitaph chosen by Hughes — EVEN AMIDST FIERCE FLAMES THE GOLDEN LOTUS CAN BE PLANTED — perhaps encourages their obsession.

Jones says Plath herself dismissed the “yearning illusions of afterlife” in a poem he cites, “November Graveyard,” which is “possibly set in the very place she finally came to rest.”

At the essential landscape stare, stare Till your eyes foist a vision dazzling on the wind: Whatever lost ghosts flare, Damned, howling in their shrouds across the moor.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Part 1 of 2. Here is Part 2.

I slept in a house in Heptonstall, with mortared walls said to be 3 feet thick, in order to frustrate the wind and chill. The grey slate remains grey, even on a sunny day, charging the moors with mood. The “stonewalled patterns” dressing the dramatic fields, stand testament to the rocky ground. How many lives does it take to pull so many endless rocks, from this difficult ground? Looking forward to part 2.

Part 2:

https://www.artsjournal.com/herman/2022/09/asa-benveniste-sylvia-plaths-afterlife-neighbor.html