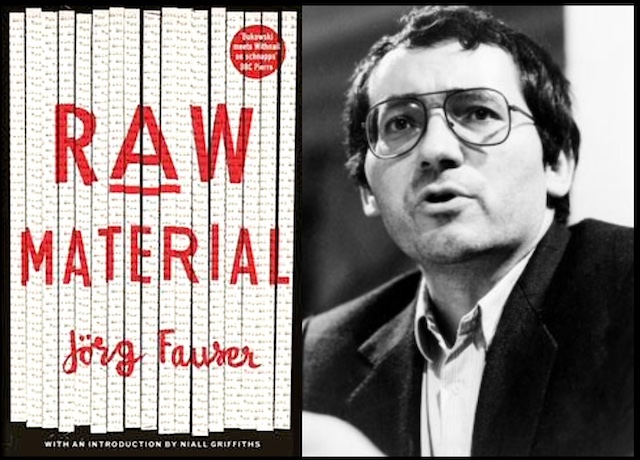

Lou Schneider liked his manuscript of Stamboul Blues and got him started as a published writer. It was the cold junky eye, the alienation and disillusionment, the unemphatic humor—acid but deadpan—that appealed to Schneider, though perhaps I’m projecting what appeals to me.

The story goes like this: After rejections from all the major German publishing houses, Fauser meets Gutowsky, “a short, portly guy about my age. I picture him as the son of a candy factory boss in the Levant, but now Destiny seemed to have selected him as my first publisher.” Gutowsky tells him Schneider is a literary expert who advises him on what to publish and says his manuscript is “heading in the direction of cut-up. That’s why we want you for our list. The German cut-up authors. … You should go see him in Mannheim as soon as you can.” Fauser says he’s broke. The scene in this roman à clef continues like so:

He twisted his mouth, as if he’d just discovered a new cavity in one of his molars. Money was evidently a painful subject for Gutowsky.

“OK, then,” he said after a stifling pause. “Come to the office tomorrow and we’ll give you the fare to Mannheim. Look,” he added, as if he now had to make up some lost ground, “we’re a little short at the moment. The good old revenue office. But when I publish your book, of course you’ll get an advance.”

“And what direction is that heading in?”

“Five hundred marks,” Gutowsky said with a squeak in his voice, seeming to reveal the absolute limit of what he could afford.

You’ll have plenty more fun with this chap, I told myself, as I wandered up to the hash meadow … That summer drugs were cheaper than books, unless you were writing them yourself.

º º º

Lou Schneider fetched me from the station in Mannheim. He must have had a nose for junkies and ex-junkies, because he picked me out of the crowd as an experienced detective might a wanted pickpocket. He looked more like a crime reporter from an American gangster film than an external reader for an avant-garde publishing house, but then again I know I didn’t exactly have the air of an aspiring young author about to publish his first novel with Suhrkamp or Hanser. He lived in the attic of an old house in the centre of town. A cat prowled around his flat. The coffee was strong. We smoked the same brand of cigarettes.

“Good work,” he said, rapping his knuckles on the manuscript of Stamboul Blues. “Just a few lines to edit out here and there, some quicker entries into scenes and transitions, then it’ll be superb.”

“Really?”

“Sure thing, amigo. Take the beginning. If you delete the first two lines and go straight into the toilet where the two guys are shooting up, then bang — you’ve got the scene licked. Just get rid of the ceremony — who wants Martin Walser when they can have Burroughs?”

“Ask the booksellers.”

“Oh yes, it drags a bit here. And, then again here, in chapter two: introducing that old Lasker-Schüler woman all of a sudden, it jars somewhat. She doesn’t belong at all.”

“But I began with poetry.”

“There’s only been one good German poet, and that was Dr. Gottfried Benn. But even Dr. Benn can only exist as a shadow in this text. . . . .

In an hour we’d gone through the manuscript. Although I had nothing to compare him to, I couldn’t imagine a more capable professional than Lou Schneider. All the waiting and anxiety had paid off. As a publisher, Gutowsky was neither fish nor foul, but Lou Schneider was the whole menu including wine, coffee and cognac at the end.”

To those in the know, Lou Schneider is Carl Weissner, master German translator of American and British dissident writers like Nelson Algren and William Burroughs, J.G. Ballard and Allen Ginsberg, Frank Zappa and Charles Bukowski, Charles Plymell and Malcolm Lowry, and a writer himself (as magnetic a storyteller as any of the dozens upon dozens he translated). Weissner also gives Fauser some literary advice beyond the particulars of Stamboul Blues (subsequently published as The Snowman).

“Tough it out,” said Lou Schneider, who was driving me home. He’d come over from Mannheim to discuss our new magazine. “Start by doing that for a few years. You’ve no idea the shit they often have to struggle through in America before they get an opportunity. When I think of some of those characters in the East Village — my God! The Scene here is a picnic by comparison. Take Carl Solomon, who Ginsberg dedicated Howl to. He’s now sixty, no hair, no teeth, he exists only with hernia trusses and compression socks and enemas and prostheses, five hundred electric shocks behind him, yet he still has an unshakeable belief in literature and is single-minded in his endeavors to fine-tune his poetry. Now that’s what I call control!”

Fauser takes this as “great encouragement” and goes off to one of his drinking hangouts, where he orders a beer and sits down next to a woman who is “almost sober and rather pensive.”

“Oh, the gentleman can still afford a bottle of Beck’s,” Nellie said.

“This evening I can pretty much afford anything I like.”

“Have you won the lottery, darling?”

“No, I’ve just found out that I’ve got to tough it out for just thirty more years, with a hernia truss, periodontitis, compression socks, beer-warmers, sciatica and enemas, then when I kick the bucket I’ll get a wreath from the chief of culture and five lines in the miscellaneous cultural news.”

Postscript: July 31 — Furthermore …

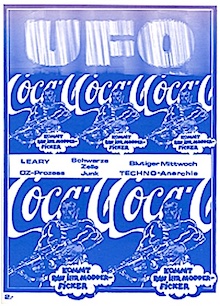

Fauser puts Jürgen Ploog in Raw Material, too, as Anatol Stern. Hidden behind the plant in the snapshot at right, there’s Fauser in Ploog’s living room with yours truly. The shot was snapped during a layout/paste-up session in 1971 for the second issue of UFO, a little magazine published by Udo Breger. At that time Ploog was already revered as something of an underground hero by other underground writers. He took it with a large grain of salt, but it pleased him. The fact that he was a Lufthansa pilot flying 747s around the globe, and had a deluxe flat in Frankfurt, and a beautiful wife may have helped to put them in awe. In any case, piloting 747s across the world did something strange to his sensibility besides giving him a bird’s eye view.

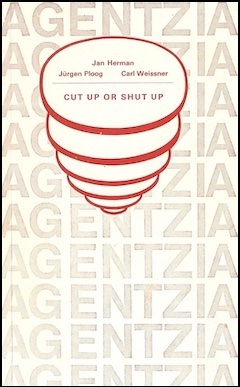

When Ploog retired from Lufthansa and came to New York in later years around Christmas time on visits to family in the Connecticut burbs, he would take the train into Grand Central to meet me for oysters and drinks at the Oyster Bar. He, Carl, and I co-wrote CUT UP OR SHUT UP, published in Paris by Agentzia in 1972, and he loved reminiscing about the old days—but only up to a point. He told me he had gone to art school and decided he could never make a living as an artist. So he applied to pilot school because he had great eyesight and passed whatever test they gave to qualify. In other words, he was never a military pilot, the kind of candidate who was generally recruited.

Now have a look at his artistic eye in late books like Film Flesh.

Interesting stories here, thanks Jan.