Some of her pieces are to be exhibited at Art Miami (Nov. 30 – Dec. 5, 2021)

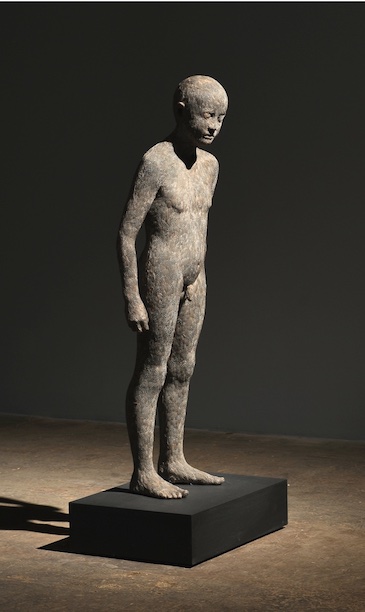

These sculptures have a striking “innerness,” an interiority of gaze and stance. In all their variations they express a human connection to animal origins. Is that what you intended?

GLENDINNING: I like the idea of the works being internalised as if contemplating themselves. Sometimes this is deliberate and sometimes this is how they turn out — so to speak. I think it is because in some ways I want the sculptures to feel as human as possible. If they are self-engaged rather than looking out, I feel they might have more of a human presence. And I am interested in the inner animal, in our subconscious and how we think of ourselves, how we are connected to animals and nature, or are separate and in charge.

They also have a primal quality, which seems to me partly a function of their feathery or furry surfaces.

GLENDINNING: I heard that the gene for feathers had been discovered, and it made me think of the gift of flight and the myth of Icarus. I made a series of works in wax of sleeping feathered children around this idea.

I started to think of how these feathered children would feel. Would they be human or animal? At the same time I was listening to some lectures on psychology, and how modern humans show behavioural and emotional tendencies that would promote the survival and reproduction of prehistoric ancestors (much more than they do us). I wondered if these prehistoric behavioural reactions are like an inner animal. The bit of ourselves we cannot control, the feeling of instinct, of second nature, of the hairs on the back of our neck. Are these our prehistoric reactions? Our inner animal? Is this how we reconnect with nature?

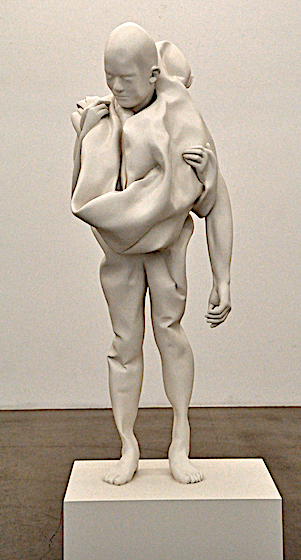

Some of your sculptures look malleable. They are not like Oldenburg’s soft sculptures, but they look soft and folded. (Together, for example).

GLENDINNING: Those works are in a way like backwards moulds. I make the sculpture and then cast it into rubber, I pose the rubber and then cast it into a solid material. I love this process as it forces mistakes; it is like mending and breaking work and trying to find the in-between in an attempt not to overwork pieces, which I am very prone to do. This series is an ongoing investigation into the physicality of a mental state: the ghost in my machine’. How we feel, how we look in different mental states.

I see you are also a poet. In fact, your terrific poem “My Animal,” which applies to My Bear, among other pieces, actually addresses that ghost from the inside out. So I will quote it whole.

My Animal Inside the animal stirs stretching limb and pulling flesh amongst the twisted guts and unchewed food. The creature grows in skin and bone from skull to toes it pulls me in. With the slow pulse of red flows it pumps itself to every limb. I wrestle logic against its grip argue fact to stop its fix. But each time it comes and goes part of me wishes it was always here.

GLENDINNING: My ideas often start with short phrases or poems, but I wouldn’t say I am a poet. They are more a means to an end. A way of noting down an idea or thought quickly. I love reading poetry, I think because I’m quite dyslexic, I have always found poetry accessible and very inspiring.

Where are you from? And did you start out as a sculptor?

GLENDINNING: I am from Somerset; I grew up here and live here now, so I haven’t moved far. I studied fine art after school and did painting and printmaking for a short time at college, but I was quickly drawn to sculpture. I love making things. I worked in a bronze foundry for a while, which was very helpful technically.

Any particular influences?

GLENDINNING: My husband Mark Merer is the biggest influence on me. He is a sculptor / land artist and also makes some buildings. He has an entirely different approach to making work and does extraordinary landscapes and objects with such ease it is often annoying. We work separately but discuss and criticise each other’s work, despite our work being very different. I think my parents influenced me. They were both G.P.s (physicians with a general practice) in a small village, and my grandfathers were both surgeons. I had access to a lot of medical books and I have my grandfather’s surgical tools which are wonderful objects.

Also Gerard Bellaart has been a big influence. I have known him for a long time now. I love his work, the energy and intrigue in it; and his integrity to it has always inspired me. I love Louise Bourgeois and always come back to her; Berlinde de Bruyckere; Kohei Nawa’s deer, extraordinary and beautiful; Kiki Smith’s work; Erwin Wurm is funny; Rebecca Horn, and Ronnie Horn. I recently saw a wonderful installation by Shipla Gupta called “Sun at Night” at the Barbican. There are so many wonderful artists. I could make a long list but that probably wouldn’t be very much help.

Thanks for taking the time to reply. I know you must be busy preparing for Art Miami. Best of luck.

oeuvre Glendinning—a few notes:

always a great sense of urgency and daring

objective; to project what is visible within

(not rest with what may appear already

accomplished)

imagination always of the essence.

images imbued with movement—

emotionally charged to the utmost.

the work forever rallying towards a form

that endures & gives increase.

Here’s an apt coincidence from the current issue of the New York Review of Books

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2021/12/02/the-minds-body-problem/

John Gray on THE MIND’S BODY PROBLEM (reviewing Melanie Challenger’s new book: “How to Be Animal: A New History of What It Means to Be Human”):

We know from evolutionary biology that humans emerged from the natural world. At the same time, many think we have cast off our animal origins; some think we can direct our future evolution. This discrepancy between what we know from scientific inquiry and the image we have formed of ourselves is Challenger’s central theme: “The truth is that being human is being animal. This is a difficult thing to admit if we are raised on a belief in our distinction.”