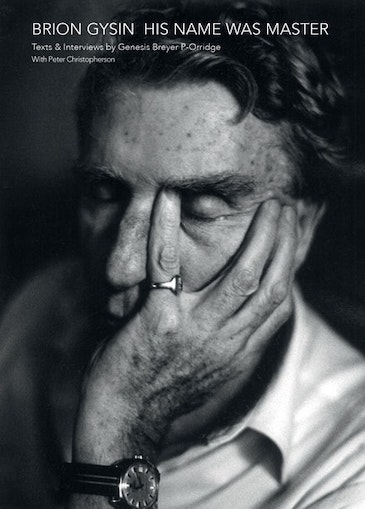

Have you ever seen a more revealing photo of Brion Gysin than the one on the cover of BRION GYSIN His Name Was Master: Texts & Interviews? It shows a profound sense of dislocation, something Gysin often talked about but rarely showed in his demeanor—which was characteristically grand and worldly and laced with humor.

Texts & Interviews by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge

With Peter Christoferson and Jon Savage

Portrait of Brion Gysin © 2018 by Ulrich Hillebrand

Trapart Books, 2018

This sprawling book by Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, with Peter Christoferson and Jon Savage, offers Gysin in talking mode. It is Gysin uncut. Having already been comprehensively reviewed in The Brooklyn Rail, it needs no review from me. More interesting than anything I might have to say is an excerpt from one of the interviews with Savage, which gives Gysin’s account of his brief, teenage involvement with the Surrealists.

°°°

Brion Gysin: I’d met this Greek who knew the Surrealists, and he introduced me to them within the very first few months that I was at the Sorbonne. And I hardly ever went to any of my classes after that…They liked my drawings, and then I met their whole kind of ‘group,’ and everything…

Jon Savage: WHAT WAS GETTING INVOLVED WITH THE SURREALISTS LIKE AT THAT PERIOD?

BG: Oh, that was very overwhelming, and very inclusive—inasmuch as they were the dominant group in Paris at that moment, and had been the first, in a way, to turn an Art movement into a terrorist Political Party…and had allied themselves with leftist politics, on one hand, and the sort of ‘Haute Couture’ world, on the other—so that they had a nice spread between…you know, left-wing Duchesses, and Communist millionaires…and Trotskyist intellectuals. And they covered the ‘scene’ in the thirties here [in Paris]. It was, you know, people who had left the movement, for one reason or another because of the sort of ‘Party Politics’ that…It was a Party, it was really definitely a terrorist Party, where you were supposed to think Surrealist, work Surrealist, eat Surrealist, and naturally, of course, dream Surrealist…and it was run by…an iron hand…! Breton was a tyrant. And he eventually lost his power. But the whole thing was a very dubious enterprise, I thought, such a dubious enterprise, that I was very quickly expelled for “sedition.”

JS: EX-COMMUNICATED.

BG: Ex-communicated in full flight! In 1935, I had been to Greece that summer, and had come back with a series of very finished drawings—which I still have, unfortunately—and they had agreed to organize an exhibition of just drawings. And everybody in the group participated, and that was the only time, even, that they had Picasso…[he] went along with them. It was the only time that he exhibited with the Surrealists, who were naturally flirting with him like mad…because they had lost Aragon, and Tzara, who had left the Party for one reason or another…expelled by Breton—more power politics. And they had all become members of the Communist Party. Picasso had not YET joined the Communist Party…I’ve forgotten when he did…I think it was after the Spanish Civil War, the next year, in 1936, that he joined the Party. But I still went on seeing Picasso. I went, actually, to the Spanish Pavilion at the World’s Fair of that year and saw him over the two or three weeks that he painted the famous “Guernica.” I saw it in various stages as he changed it from one day to the other…and went home, furiously, and laid out more drawings, and then came back the next day and then changed it.

JS: DID IT CHANGE, FROM HOW HE SAW IT AT THE START?

BG: Oh yeah. Sure, I mean, I saw it change right on the wall, before the exhibition was opened.

JS: HOW DID IT CHANGE? DID IT BECOME SORT OF HARDER, OR…

BG: Harder, and richer, and tighter, and more highly organized, from the point of view of…

JG: AND YOU GOT EX-COMMUNICATED.

BG: I was ex-communicated very brutally for a tender nineteen-year-old… I went [to the exhibition] thinking that something might be necessary…Keep an eye on things…I went early…The exhibition was to open at six o’clock in the evening, and I thought, “I think I’d better go there about five.” And I got there about five, and I found Paul Éluard unhanging my pictures, and I said, “What’s this all about?” And he said, “Orders from Breton.” And very shortly after that Valentine Hugo arrived, and she had been Breton’s mistress in some period or other, and she too had been expelled from the…ex-communicated from the movement, and was on very bitter terms with Breton, so she took up my defense, which was, at the same time, rather embarrassing Then there was no question about it. I was OUT. I mean, if I was being defended by Valentine Hugo, all I had to do was go off with her…I went off with her for a while…Some six or seven years ago, a dealer had collected all that sort of stuff, and he had bought the entire…her succession, when she died, which must have been about ’73, ’74, like that. I read in the newspaper, in ‘Le Monde,’ that letters were sold, and e-v-e-r-y name in the whole list was of very famous people—except my own. But apparently MY correspondence was also sold publicly, along with everybody else[’s] of that period. But that also never added up to anything because I never…um…I didn’t admire her painting, I didn’t really particularly want to be associated with her—there was no future in that for me. There was SOME future in that for her, to have a handsome young dissident around […] I just couldn’t see myself becoming a lapdog in her house…and I sort of went off on my own, and then my first one-man show was in the Spring of 1939. The same gallery which had been on the Left Bank had moved off to very Right Bank…Right off the Champs Elysée there, in the Rue D’Avignon, and I had a v-e-r-y sort of…’social’ opening. All sorts of…

JS: QUITE CROWDED?

BG: Mmm, sort of…Everybody who was passing through at that moment was there. So that’s why some of those early pictures of mine got so dispersed. […] And I then met the Surrealists again in New York, where I got to by 1940. They trickled in a little bit later, for one reason or another. I was quite well established, and of course I spoke the language—which they didn’t—and I had a big studio right on the corner of 56th Street and Madison Avenue, which was very central…I just sort of opened my house to them and gave big parties, mostly with Peggy Guggenheim, who was an old friend of theirs…Naturally, she was one of their patrons, and was always a friend of mine. And a patron I guess, in a way, in as much as she gave various pictures of mine to museums around the world. My motto was, “There’s no point in carrying quarrels from the old world to the new.” So we would go through that AGAIN, if necessary.

Out of that, nothing of any interest came, except my friendship with Matta at that time, who hadn’t yet joined the Surrealists. In 1935 he was still in Chile someplace, as an architectural student. He had come in the interim, and had joined the group, and so then I met him, and we became intimate and worked together, and you know, drew all night in front of live models and things like that. Which you wouldn’t quite suspect from…from any of us. But we did.

JS: WHY DID YOU GO BACK TO NEW YORK? HAD YOU BECOME SORT OF TIRED OF EUROPE, OR DID YOU WANT TO GET…

BG: Oh no…One RAN to New York—what do you m-e-a-n…? 1939, 1940…! One didn’t want to be anywhere ELSE! E-v-e-r-y-b-o-d-y came to New York. It was a V-E-R-Y extraordinary city at that time. It REALLY was Babylon, very little English spoken, anywhere…whether it was in the streets, or in a bus, or in an elevator, or wherever you liked. There was every language spoken there that you could think of, except English…American English. And sort of EVERYBODY from Berlin was there, EVERYBODY from Vienna was there, EVERYBODY from Budapest was there, like everybody that COULD get there who wasn’t already dead in a concentration camp, was in New York. Everybody from France—at least one half of France—came, and certainly all the painters came who could. They ranged all the way from the Surrealist group…That means Max Ernst, who married…or was married BY Peggy Guggenheim, and Matta of course, and Tanguy, who had married an American…on and on. Masson and his whole family were there, and then people that weren’t of the Surrealist group, the most important painter was Legér, who spent all that part of the War in New York. One saw him regularly. And there were all the European composers, they were there, all the musicians were there…It was an extraordinarily brilliant period. It was really [an] amazing three or four years.

Brion did anticipate disappointments and was rarely disappointed. A grand and important individual.

Yes, Important. Grand. One of a kind. You knew him well. So I defer to your judgment. Nevertheless, I don’t see how he was not disappointed. But ah… now I get it. Such wit unbends the mind.