There are day poets and night poets. Here is one of each.

I should perhaps mention, in case anyone gets the wrong idea, that I make no value judgment as to the greater or lesser worth of “day” vs. “night.” I had so much fun reading Suspicious Circumstances that it felt as good as getting high, no drugs needed. The wit and wisdom of its vignettes—really prose poems laced with laughter—dissect the customs and dispel the dreariness of ordinary life. They are a much-needed provocation, like Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen turned inside out.

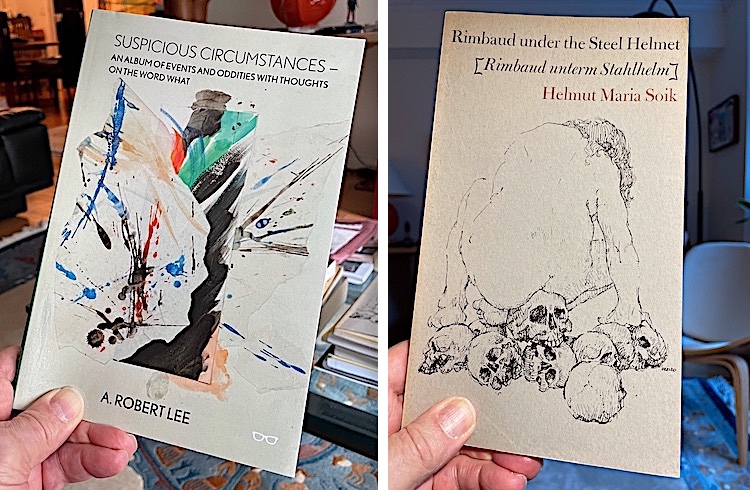

from SUSPICIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES: An Album of Events and Oddities with Thoughts on the Word What

LEND ME YOUR EARS You're on the phone. The mobile. The landline. And suddenly there's one of those buzzes. Kind of cable phlegm. Rust sound. Maybe the like of a flailing bluebottle or gnat. You try to muster every listening fibre you can to make out the plaintive question Can you hear me? There is an almost laughable fatuity with which you reply Barely, or Just about. Or even just No. How to say you can't hear to someone you have just heard? It's like saying you don't speak Bulgarian in Bulgarian. The voice at the other end, moreover, seems to be whispering yet further things for you not to hear. Miniscule verbs. Nouns at long distance. Whole phrases reduced to snippets. Words resemble pinpricks. It's an acoustic smog. You begin to long for one of those film battleships in which the John Wayne caption says Now Hear This. As if you could. What, too, at a theatre, or during a recital, when your companion leans and says something in your ear? Except your ear, well, doesn't hear. You can hardly start a whole conversation during the play's vital moment or a violin vibrato. There are also all those times that glass gets in the way. I mean a train or bus window. Even a house or office pane. You can see lips moving, an arm gesturing, maybe a finger pointing. You hear a half-shout, a half-name. But for the life of you can't quite make out what's being said. A shared frustration can be yours when a friend, or someone in the family, starts telling you about what happened last Thursday down the road. An argument among neighbors perhaps. A loudspeaker braying politics or a new supermarket. But, according to what you're being told, the detail had collapsed into a blur. I could hardly hear it, you in turn hear. So it does not come as untoward that the yearly medical includes an ear test. You have all the other good things to go through of course. The barium meal, and if you're really lucky, the endoscopy. The drawn blood with a needle that goes slightly askew. The ultrasound during which the gel slithers off your abdomen and causes a mess on your clothing. Not a few examinees get a case of dizziness when being tested for lung capacity and have to blow into a small tube wedged between the teeth. The tube gets embroiled in saliva, causes half-choking, and whoever is being tested finds they've lost breath even before the procedure gets underway. Doctor or nurse patience doesn't take away the feeling of something close to foolishness. But then come eyes and ears. The former you are all know-how because you've been going to eye people since you were three. And the next line? You read away with those monstrous meta-specs perched on the nose. A new lens is slipped in. Is that better? After which the ears. The last time I was at a clinic where the full medical card was being gone through the ear-testing had its own cubicle. Not a little like a small-scale broadcasting studio. Step inside and it feels almost physical silence. A local version of what you think the CERN accelerator must be. Or an anechoic chamber. Certainly it's whatever, and wherever, is meant by sound extraction. Hanging before you are earphones and a small button ready to be pressed. You get seated. You get the lids nestled around your head. You even see your face reflected in the glass. Costmonaut X. Chief astronaut Y. The beginning nod is given to you by the white-coated person in charge. You have of course been briefed. Press the button when you hear one of the pitches. Each a species of short whine or single bell ring. Off you go. Concentration. You press at intervals for the length of the pitch. Each of these continues until the sounds get fainter, weaker. It is here that you can go deeply off-key. Did you hear a sound or did you not? Are you more and more becoming twitchy, pressing as though so commanded by some inner-ear geist? Are you now so ear-scrambled that you can't tell sound from silence? Maybe there's an equivalent of déja vu? Perhaps déja écouté? Either way there's sweat to the brow, a sinking sensation. With which out from the booth you come. Star-navigator. Yuri Gagarin. Captain Kirk. Only to hear in quite the loudest of words I'm afraid you'll have to do that again.------------------------------------------

from RIMBAUD UNDER THE STEEL HELMET (translated from the Germany by Georg M. Gugelberger and Lydia Perera).

Remarks of Tu Fu concerning some of his contemporaries: It could be argued that ten thousand verses by celebrated poets were written in this century to no purpose. Endless were discussions in articles and dissertations. Emperors and princes wrote their commentaries. Missing are the answers to these questions: Did they change the world? Did the murderers waste away of hunger and wretchedness? Did the madness of love forsaken ever leave the lover? For the emperor's seal affixed to the north his soldiers' bellies rotted in the yellow grass of September. Who did not hear from the refugees, how human flesh was boiled in the provinces? From a padded sedan chair it is easy to see children freezing in the snowstorm. For ten of your orchids nurtured in the hothouse one could build a lovely fire under the pot. I've already told too much of the truth. The uncomfortable is soon forgotten in exile. In the evening my hut on the northwall lies buried by snow. Despair overwhelms me when the cold screams out of the ashes. I wish to die, yet am forced to live. Prime Minister Li Sa made it a point to spread the word that my verses had gained in depth ever since hunger was my guest. I looked so pale my friends felt. I wore the actor's mask of death. I would have to fatten myself. The host at the tea-house cannot understand where Tu Fu has kept himself so long. Mister Wang, the barber thinks: "I'll invite Tu Fu to supper let the poor soul eat his fill. A glass of sake buys a cheap lesson. Tu Fu's monologues are books for which I have scant time." Life is hard. Under my shirt the triple chain of coins weighs my neck down. I, Tu Fu, stand hungry by the window and beg the sun to provide a little bit of help with my verses.

Hi!!!! It’s me Julia! I love this prose poem! It creates so much meaning, and even though some words don’t exactly make sense to me, different ways that I say and express them tell the whole story.

And, I meant both of them. Both of the prose poems.

I am SO pleased to hear that. Thank you!!