UPDATED: To get the drift of Aufzeichnungen über Aussenseiter, I’ve been typing pieces of text into google translate. It’s a helluva time-consuming job, like re-setting type you understand. Matthias Penzel, who organized and edited the collection and wrote an afterword, tells me I should have better things to do with my time. But it’s more than worth the effort, though I wish the book were in English so I could enjoy it cover to cover the way kraut readers can. But the texts are a thrill even for a no-kraut-can’t-travel reader. It’s just obvious how classy and swinging the whole thing is! I love everything about it. Love the thoroughness. Love the layout. Love the legibility. Love the documentation. Love the flaps. Love the way the book feels in the hand. I will have more to say when my fingers return to normal.

POSTSCRIPT: March 30—With my fingers recovered I managed to find a translated excerpt. Here it is, slightly improved. Unfortunately it doesn’t give the actual flavor of Carl’s stylish prose.

Buk Sings His Ass Off

I had been in contact with Bukowski for several years. I knew him from countless letters, from his books, from the manuscripts he sent me for Klacto/23 , and when I first visited him in Los Angeles in the summer of 1968, I also got to know the “Bukowski legend”: the one in the poster shops of New York and San Francisco and in the ecstatic articles of his admirers in the editorial offices of American underground magazines and newspapers. Since the late 1950s there had hardly been a “little magazine” of any importance in which he was not regularly featured. The run on Bukowski finally began in 1965 when The Outsider—alongside Evergreen Review and Kulchur, one of the most important literary magazines of those years—declared him in a special issue “Outsider of the Year.”

At that time he sent me a copy of his letter to the editors in which he reported in detail about his last suicide attempt and only at the very end, almost a little disgruntled, did he take note of the “honor” and added: “I will stick with it — and you know me good enough not to get that down the wrong throat — : Personality cult is shit.”

When we met I told him that I had kept hearing from people who only knew the success but not the man himself, that Bukowski was a first-rate conman if he pretended to be like [he was] just before snapping off; in reality, he now has a large bank account and probably drives a Cadillac paid for in cash; he probably also keeps a little homo who does the paperwork for him, etc.

“Shit,” he said. “It’s all cold coffee. Nothing has changed in my life, except that all the hype takes away my desire to write. In any case, I have no plans to subscribe to the golden shithouses of culture. Look around: I still live in the dirt, in the slums, on Hollywood’s Skid Row. But that’s something I know how to deal with, so I’m not really keen on that to change.

“That, plus a series of lousy jobs, ruined health, a dose of insanity, a broken-down ‘57 Plymouth, a battered face, screwed-up women’s stories, a few magazines & little publishers worth writing for, and a few everyday vices like betting on the horses and drinking is all I’ve had so far & everything I needed to work. When writing makes me a few hundred dollars every now and then, I immediately get the feeling that I’m slipping, that I’m about to sell out. And I see to it that I bet the money on the next race or on a binge. Only when I’m at zero can I get back on the machine and try to continue.”

“And when I write, then despite the last unnerving night shift (as a letter sorter in the post office — CW), despite the last losses, despite hemorrhoids and gastric rupture, despite the last prison sentence for trespassing in the act of assault and coercion, despite the fact that I puked blood half an hour ago, and despite the check from Evergreen Review or Playboy, and despite the stupid assholes who put that shitty image of the “tough guy” on me or who celebrate me as a Hemingway gone wild or the slum-god from the sewers of Los Angeles or what do I know …

“Many who read me seem unable to understand that I am only writing to find out whether or not I am already completely mad – and that means: whether I will survive, want to survive, or not for the next 24 hours; whether I am still able to face the truth and then put it on paper instead of just doing literature.

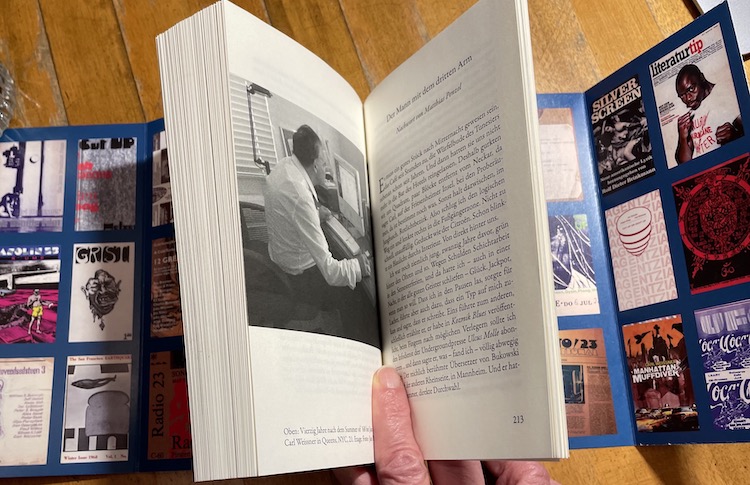

“In other words, when I say that I cling to that typewriter by the window every day like a rusty machinegun after the enemy has rolled over me to the right and left, then that is not a lyrical phrase. My vocabulary has shrunk to the last remnant in these years, but with this remnant I try to hammer out what’s inside.

‘My vocabulary has shrunk to the last remnant in these years, but with this remnant I try to hammer out what’s inside.’ — Buk

“All the years I’ve worked in slaughterhouses and gas stations, on assembly lines and in subway tunnels, etc., make it impossible for me to accept the well-established word for its own sake. There has to be more in there for me, otherwise I’m just another suicide in a dirty room or in the gutter or in the sea or in the gas cloud. And if I leave the stuff out of the house, if I send it out and have it published, it is because I know that there are a few hundred or a thousand junkIes out there that are exact duplicates of me, and because I managed to survive to this day.”

“In addition to the pure instinct for self-preservation, a shot of ego could of course also be involved: Charles Bukowski on a piece of paper, you understand? So that I can have the feeling that if I fall over in the drunk tank or get my bowels cut out or my soul or whatever, that I have saved at least a fraction of this shitty, screwed-up life … “

I think that said a lot. Not about the “phenomenon” Bukowski, not about the “legend” Bukowski, but about the American person Charles Bukowski … one evening in the summer of 1968 with the sixth can of Pabst Blue Ribbon beer in his dilapidated apartment on DeLongpre Avenue in Los Angeles.

This perhaps also says something about Charles Bukowski, the son of German-Polish immigrants, born in Andernach am Rhein in 1920, who came to America at the age of 2, grew up in the slums of the big cities, had his first criminal record as a youth member of a gang, and later studied journalism (dropped out), then gained experience as a corpse washer, advertising copywriter for a brothel, furniture packer, night porter, butcher’s assistant, sports journalist, garbage-truck driver, dockworker, pimp, editor of literary magazines, alcoholic, prisoner, and consequent outsider … about this Charles Bukowski who I’m with on the night of August 8, 1968, at a party at Henry Miller’s house (Miller was also the son of a German mother). When Buk was completely drunk, he hit the host on the shoulder and exclaimed: “Henry, we Germans are, God knows, the biggest assholers in the world! “, whereupon a battle of words developed, which was for the most part fought with German expletives and ended with Miller crouching at his battered Yamaha grand piano and hammering the Marseillaise while Bukowski roared the Polish national anthem.

This Charles Bukowski is the author of Notes of a Dirty Old Man (originally written as a series of weekly columns for Open City, the Los Angeles underground newspaper), which also mentions Jack Micheline, one of the last active street poets of the Beat Generation; of Bukowski’s encounter with Neal Cassady (hero of Kerouac’s On the Road ) a few days before he died of an overdose in Mexico; and Harold Norse (from the circle of the “Americans in exile” around William Burroughs in Paris in the early 1960s), in whom Bukowski — like himself — diagnosed the Frozen Man Syndrome, the unmistakable sign of the self-chosen outsider existence.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher from Carl Weissner: Notes on Outsiders: Essays and Reportage. Edited by Matthias Penzel. Verlag Andreas Reiffer, Meine 2020 (first printing: Melzers Surf Rider. Melzer Verlag, Darmstadt 1970).