James Grauerholz presented this essay in Boulder, Colorado, at the Naropa Institute’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in 1999 on the 25th anniversary of its founding. He describes the role that Eastern philosophy played in the life and work of William S. Burroughs. The essay was first published in the 2004 anthology “Civil Disobediences” (Anne Waldman and Lisa Birman, eds.) and has been illustrated and edited for posting here.

By JAMES GRAUERHOLZ

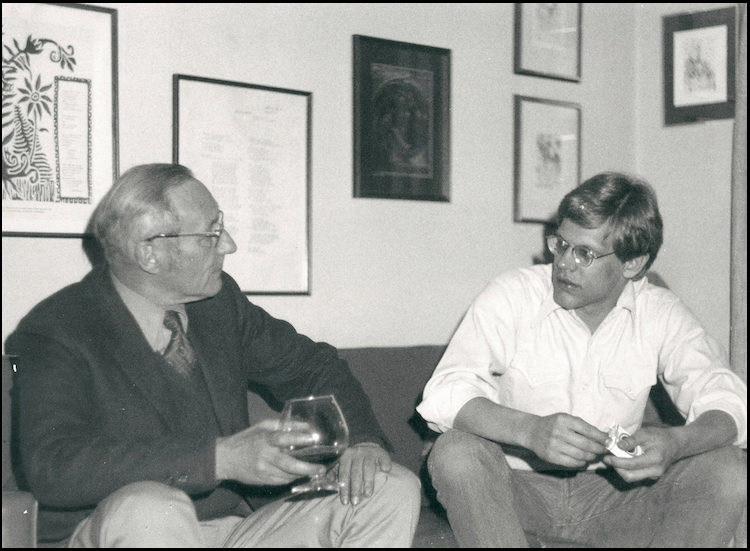

Photo © by Jon Blumb

I was William Burroughs’s companion and collaborator for the last twenty-three years of his life, beginning soon after he moved back to the United States in early 1974 until he died peacefully at age 83 on Aug. 2nd, 1997. William was not a Buddhist: he never sought or found a “Teacher,” he never took Refuge, and he never undertook any Bodhisattva vows. He did not consider himself a Buddhist, nor—for that matter—did he ever declare himself a follower of any one faith or practice.

But he did have an awareness of the essentials of Buddhism, and in his own way, he was affected by bodhidharma. Because of this, and because many of his closest friends were Buddhists (see: Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, who often considered him one of their Teachers), Burroughs and his work can be explored within a Buddhist setting. So, since we are all here at a learning institution founded by Buddhists, this is perhaps an interesting way for us to approach his life and work.

William spent a great deal of time in Boulder and was effectively a resident of the town for two years, during 1976 to 1978. His first visit was for two weeks in 1975, and after he set himself up in “The Bunker” (his New York loft) in late 1978, he continued to make annual visits to Naropa until 1989. There are many people in Boulder who knew William during those years.

Let me apologize in advance for any doctrinal or nomenclatural errors I may make. I am by no means an “expert” on Buddhism. But before I talk about William’s life, I would like to say a few things about my own, in particular the years before I met William, so that you will have some context for my observations

My first awareness of Buddhism came from Schopenhauer.

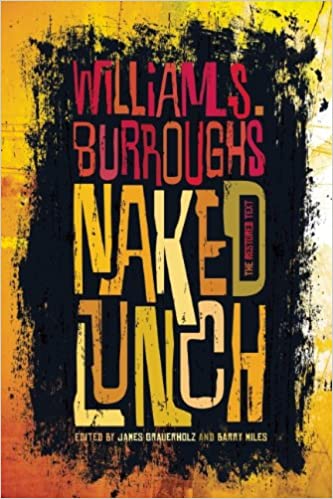

I was born in southeast Kansas in 1952, and my first awareness of the existence of something called “Buddhism” was in my grade school days, when—reading selections from the work of Arthur Schopenhauer in the “Great Books” series—I encountered his remarks on Buddhism, as found in his 1818 work, The World as Will and Idea. Like Schopenhauer (and everybody else, probably), I had an unhappy childhood, and I gravitated naturally towards the work of classic writers and philosophers whose view of human nature and human existence was essentially pessimistic: Swift, Voltaire, de Sade, Sterne, the Book of Ecclesiastes … and Burroughs, of course. I was fourteen when I stumbled onto his best-known novel, Naked Lunch.

Schopenhauer’s intellectual embrace of Buddhist principles was based primarily on his impressions of the First Noble Truth, as Buddhists call it: the idea that the essence of life itself is suffering, dukha, or “unsatisfactoriness”—the First Mark of all conditioned dharmas (the other two being impermanence and egolessness). If you will indulge me I’d like to quote from the Buddha’s Sermon at Deer Park in Benares: “Now this, monks, is the noble truth of pain: birth is painful, old age is painful, sickness is painful, death is painful, sorrow, lamentation, dejection, and despair are painful. Contact with unpleasant things is painful, not getting what one wishes is painful. In short the five skandhas [the five “heaps” of human personality] are painful.” My first contact with this scripture was decisive for me; it had, as William would put it, the aspect of “surprised recognition.”

I went to the University of Kansas in Lawrence at age 16, and by my sophomore year I had begun taking Eastern Philosophy classes from Dr. Alfonso Verdu. Dr. Verdu was a very interesting Catalonian who had studied in Germany under Hüsserl, the phenomenologist and a student of the dialectical materialism of Hegel. Verdu went on to study the history of Eastern philosophy at various places in Asia. He was also a friend of the late Dr. Agehananda Bharati, a German-born Tibetanist whom Verdu brought to KU for a one-semester class, which I was also fortunate to attend in 1971.

I was not drawn to the Dharma by any predisposition towards finding a Buddhist Teacher.

At KU Dr. Verdu was teaching a staged series of classes covering the development of Eastern thought from Hinduism to Zen, emphasizing the evolution of these beliefs according to the Hegelian dialectical model of “thesis—antithesis—synthesis.” I followed Dr. Verdu’s course of classes through my last three years at KU, but I dropped out of college just before the end of his class on Zen Buddhism. By that time I personally had become “too Zen” to stay in school any longer—or so I thought, at that tender age. I considered myself then a pratyeka buddha, or “lone-wolf boddhisattva,” with no Teacher and no sitting practice, as such.

I hung around Lawrence for another year or so, playing guitar in local bands, and so forth; then I went to New York and met William Burroughs. That meeting set the stage for the rest of my life.

So as you see, I was not drawn to the Dharma by any predisposition towards finding a Buddhist Teacher whom I could follow, and with whom I could take Refuge, nor by any fascination with Buddhist symbology or ritual … my inclination basically originated in an artistic and intellectual attraction to any doctrine that could explain why I was so unhappy and so disgusted by the world of the so-called “adults” all around me. Of course, in a broader sense you could say that at age 21 I found my “teacher” in William himself, and I could not deny that.

From his earliest childhood in St. Louis, Missouri in the 1920s, Burroughs was alienated and repulsed by the personal and social hypocrisy that he could not help but perceive around him, even at the age of 8 or 10. He was terribly shy, and frightened of the other children, but at the same time defiant in his own beliefs and inclinations—including his homosexual attraction to some of his classmates. A sense of being fundamentally “different” from the others marked his childhood, and never left him all his life.

From earliest childhood William was alienated and

repulsed by personal and social hypocrisy.

The Burroughs family’s economic circumstances—while never approaching the kind of wealth that is often wrongly associated with his family (thanks to Jack Kerouac’s pseudo-biographical inventions about him)—were certainly comfortable, and he grew up surrounded by the children of the upper classes of old St. Louis and their parents. A bit like Gautama Sakyamuni, Burroughs was in childhood somewhat insulated from the phenomena of “old age, sickness and death”—but his parents’ domestic servants at that time showed him his first glimpses of the not-so-perfect world that lay beyond his family circle. An Irish nanny and a Welsh governess taught him how to throw curses and how to “call the toads.” The servants also exposed him to sordid scenes from their own personal lives as lower-class emigrés to America. Burroughs’s governess had a veterinarian boyfriend, and she and the boyfriend took little Willy along on a picnic date one day when he was about four years old. Apparently there occurred a sexual situation involving little Willy, which traumatized him.

In his twenties Burroughs saw a series of psychoanalysts in the hope that recouping this early trauma would allow him to break free of the psychic constraints and self-defeating reflexes that he felt as a lifelong curse. Then when he was thirty, in New York, Burroughs met Kerouac and Ginsberg, and after a period of several months in which he was conducting his own “lay analyses” of his new friends, his addiction to morphine, which had been recently developed, began to take the place of his analytic efforts. He had abandoned all faith in psychiatry by the age of 45, but long before that, he had concluded that the Freudian model of “cure of neurosis through recuperation of primordial trauma” was overrated.

Burroughs was also troubled by philosophical questions about the significance of language; in 1939 he had gone to Chicago to attend a series of lectures by Count Alfred Korzybski, the founder of a school of thought that he called “General Semantics.” From these lectures Burroughs took away the insight that a word is not its referent—the word has no tangible existence—and that what William called “dualistic,” or “either/or” thinking is an intellectual trap. Like Nagarjuna, Korzybski had postulated the solution: “both/and.” It was an article of faith with William that the “either/or” concept was completely mistaken, and he very often cited the “both/and” concept in conversation and interviews.

William did have in some ways—as his friend Lucien Carr put it—

‘the morals of a Boy Scout, although he’d never want you to know that.’

Although William seems to have had an intuitive grasp of the First Noble Truth (in so many words), it was only towards the end of his life that he seemed to embrace the Second Noble Truth: that the cause of suffering is ignorance. That is, William always perceived suffering—and gross forms of ignorance—all around him, but his reaction was rooted in a strong sense of self, and self-preservation … so that whatever natural compassion he may have felt was usually over-balanced by his contempt for the stupidity of Mankind, and his hatred of everything that he took as personal oppression or anything threatening his self-control.

Jean-Paul Sartre said; “Hell is other people;” the young William Burroughs said: “Other people are different from me and I don’t like them.” His response was to develop an obsession with weapons and self-defense, which lasted all his life. William sometimes affected a self-image exemplified by the lyrics of a blues song of the 1920s, which he often quoted in later years: “I’m evil, evil as a man can be / I’m evil, evil-hearted me.” But his heart wasn’t really in it, all this evilness; there was within him some strain of bedrock decency that always stopped him from elaborating himself fully in that direction.

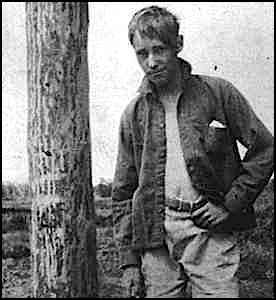

And this fertile inner ground for the growth of compassion is shown by his youthful embrace of the “alternative decency”—so to speak—of “the Johnson Family.” This was a turn-of-the-century term among hobos and the criminal underworld, referring to their code of honor: a Johnson minds his own business, his word is his bond, he gives help when help is needed, and he never offers information to the police. (Etcetera.) William encountered this alternative ethics in the memoirs of a reformed safecracker and highwayman of the old American West named Jack Black. Called You Can’t Win, it was published in 1927, when William was 13. Again, this was a decisive and formative encounter for him.

So William really did have, in some ways—as his friend Lucien Carr put it—”the morals of a Boy Scout, although he’d never want you to know that.” It’s just that William’s “Boy Scout” was the flipside of Lord Baden-Powell’s goody-goody English Scout boy: a “Revised Boy Scout”—that is to say, a “Wild Boy.” As Burroughs wrote: “A wild boy is filthy, dreamy, treacherous, vicious and lustful.” This wistful formulation confirms at least the second part of Carr’s remark. But Burroughs himself, in person, impressed most people who knew him fairly well as a gentleman: well mannered and well turned out. He could be wild and crazy in private, like most of us, but his social front was genteel and courtly. And this tension—between upper-class social manners and a thoroughly democratic, can I say Whitmanic, impulse within intimate (particularly underclass or “underground”) society—is a defining faultline through all of his life and work.

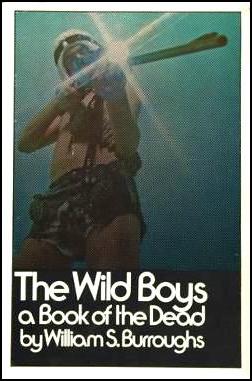

What distinguishes William’s writing in Wild Boys—after Naked Lunch and the Cut-Up Trilogy—is the emergence of hope: for the first time, Burroughs is not just ridiculing the world he has observed, but going on to fantasize another world in which he thinks he might like to live. Then the Red Night trilogy, which he wrote in his old age (1974-1987), moves steadily from the self-absorbed, sexually obsessed adolescent flights of the Wild Boys‘ narrator’s persona towards an always-older and wiser protagonist’s viewpoint; Burroughs was reverting at the end of his writing career to the self-description with which he had begun it, in Junky and Queer. And like Siddhartha he was growing into an ever-deeper sense of compassion for the suffering of others.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let’s go back to William’s early life. I’m going to quote from his letters to Kerouac and Ginsberg during 1953-1955, because they contain a clue as to where he first encountered any notion of Yoga, Zen and Tibetan Buddhism: we know that, while still living with his parents, he loved to read the boys’-adventure and science-fiction magazines of the 1920s, and Sax Rohmer’s “Dr. Fu-Manchu” novels. These goofy pop images of “yoga” etc., presented as an exotic form of self-control for the attainment of mystical “powers,” must have prompted him to send away for booklets promising to convey these “ancient secrets of the East” to young men. And we know that in his mid-twenties, in New York, he took courses from an instructor in “Jiu-Jitsu,” which was popularized as a self-defense technique in those days; no doubt these courses also carried a simplified dose of so-called “Eastern wisdom.”

Burroughs graduated Harvard in 1936 and pursued his fascination

with the criminal underworld over the next eight years. He

was probably almost always armed with a pistol.

Burroughs graduated Harvard in 1936 and was in Vienna, Chicago, St. Louis and New York during the next eight years. He pursued his fascination with the criminal underworld during that time, and was probably almost always armed with a pistol. He volunteered for service during the early years of World War II, but was repeatedly turned down; then after Pearl Harbor, he was drafted, but was given a psychological discharge. In 1944 Burroughs was back in New York, and he met Kerouac and Ginsberg through a Columbia University student from St. Louis named Lucien Carr. He also became addicted to morphine around this time.

By 1949 Burroughs was living in Mexico City with Joan Vollmer, a bright young woman with whom he felt a deep kinship despite his essential homosexuality. But as is widely known, he killed Joan accidentally in 1951 while firing one shot from a pistol at a glass she had placed on her head. Within three years he was living a life of squalid excess in Tangier, still struggling to understand how this had happened. Burroughs felt he was defending his Self not only from outer opponents, but also from an inner enemy: the Ugly Spirit, as he called it. He felt that he was literally “possessed” by an inimical, invading personality with its own will that was quite contrary to his best interests. He claimed to have felt this sense of “possession” from his early years. And in his efforts to understand his shooting of Joan, he could proceed no further than to see an eruption of the Ugly Spirit in that rash, drunken act.

His letters from Tangier to Kerouac and Ginsberg were a lifeline for Burroughs. Meanwhile, Ginsberg had been inspired to look into Zen Buddhism after seeing some Chinese paintings in the New York Public Library in April 1953, and Kerouac had found Dwight Goddard’s A Buddhist Bible in the San Jose, California, library while he was staying with Neal and Carolyn Cassady in February 1954. Although their letters to Burroughs are lost, we can see that his friends were enthusing about these Eastern beliefs as they wrote to him. (Kerouac was also going through a phase of ascetic celibacy.)

‘I picked up on Yoga many years ago. Tibetan Buddhism, and Zen you should look into. Also Tao. Skip Confucius.’ — Burroughs to Kerouac

To Kerouac, May 24, 1954, from Lima, Peru:

As you know I picked up on Yoga many years ago. Tibetan Buddhism, and Zen you should look into. Also Tao. Skip Confucius. He is sententious old bore. Most of his sayings are about on the “Confucius say” level. My present orientation is diametrically opposed [to], therefore perhaps progression from, Buddhism. I say we are here in human form to learn by the human hieroglyphics of love and suffering. There is no intensity of love or feeling that does not involve the risk of crippling hurt. It is a duty to take this risk, to love and feel without defense or reserve. I speak only for myself. Your needs may be different. However, I am dubious of the wisdom of side-stepping sex.

To Ginsberg, July 15, 1954, from Tangier:

Tibetan Buddhism is extremely interesting. Dig it if you have not done so. I had some mystic experiences and convictions when I was practicing Yoga. That was 15 years ago. Before I knew you.

My final decision was that Yoga is no solution for a Westerner and I disapprove of all practice of Neo-Buddhism. […] Yoga should be practiced, yes, but not as final, a solution, but rather as we study history and comparative cultures.

The metaphysics of Jiu-Jitsu is interesting, and derives from Zen. If there is [a] Jiu-Jitsu club in Frisco, join. It is worthwhile and one of the best forms of exercise, because it is predicated on relaxation rather than straining.

To Kerouac, Aug. 18, 1954, from Tangier:

[M]y conclusion was that Buddhism is only for the West to study as history, that is a subject for understanding, and Yoga can profitably be practiced to that end. But it is not, for the West, An Answer, not A Solution. We must learn by acting, experiencing, and living; that is, above all, by Love and Suffering. A man who uses Buddhism or any other instrument to remove love from his being in order to avoid suffering, has committed, in my mind, a sacrilege comparable to castration. You were given the power to love in order to use it, no matter what pain it may cause you. Buddhism frequently amounts to a form of psychic junk …

I can not ally myself with such a purely negative goal as avoidance of suffering. Suffering is a chance you have to take by the fact of being alive.

I repeat, Buddhism is not for the West. We must evolve our own solutions.

‘I say we are here in human form to learn by the human hieroglyphics of

love and suffering. There is no intensity of love or feeling that does not involve the risk of crippling hurt.’ — Burroughs to Kerouac

To Ginsberg and Kerouac, Oct. 23, 1955, from Tangier:

The metaphysic of interpersonal combat: Zen Buddhist straight-aheadedness applied to fencing and knife fighting; Jiu-Jitsu principle of “winning by giving in” and “Turning your opponent’s strength against him,” various techniques of knife fighting, a knife fight as a mystic contest, a discipline like Yoga— You must eliminate fear and anger—and see the fight as impersonal process.

“Suffering is a chance you have to take by the fact of being alive.” Here we see a glimpse of the First Noble Truth, but from a distinctly Romantic / Heroic standpoint: for Burroughs, it is our duty to suffer, and to learn from suffering. But he was referring primarily to sexual or romantic love, in which he had suffered much; for example, in New York at age 26 he was overcome by jealousy and heartache over a boyfriend’s infidelity and neglect, and he cut off the end of his own left little finger; in Mexico 10 years later he fell painfully for a young American who never came close to mirroring the depth of his feelings; and after Joan’s death he realized that he was in love with Ginsberg, but when they were reunited in New York in late 1953, Ginsberg rejected him as a lover.

But at the same time that Burroughs wore this emotional hairshirt, he also showed (in writings sent to Ginsberg) some insight into the self-inflicted quality of his suffering:

[Lee’s] face had the look of a superimposed photo, reflecting a fractured spirit that could never love man or woman with complete wholeness. Yet he was driven by an intense need to make his love real, to change fact. Usually he selected someone who could not reciprocate, so that he was able […] to shift the burden of not loving, of being unable to love, onto the partner. […] Basically the loved one was always and forever an Outsider, a Bystander, an Audience.”

‘Suffering is a chance you take by being alive.’ — Burroughs to Ginsberg

As for the notion of Buddhism as “psychic junk,” here is an irresistibly funny bit from Naked Lunch, the novel he was writing in Tangier:

[“a vicious, fruity old Saint applying pancake from an alabaster bowl”]:

“Buddha? A notorious metabolic junky … Makes his own you dig. In India, where they got no sense of time, The Man is often a month late. … ‘Now let me see, is that the second or the third monsoon? I got like a meet in Ketchupore about more or less.’

“And all them junkies sitting around in the lotus position spitting on the ground and waiting on The Man.

“So Buddha says: ‘I don’t hafta take this sound. I’ll by God metabolize my own junk.’

“‘Man, you can’t do that. The Revenooers will swarm all over you.’

“‘Over me they won’t swarm. I gotta gimmick, see? I’m a fuckin’ Holy Man as of right now.’

“‘Jeez, boss, what an angle.'”

These writings indicate that Burroughs misunderstood Buddhism. A straightforward motivation of “avoiding suffering” is merely another form of craving, after all. And in Mahayana Buddhism the bodhisattva vows not to seek the extinction of Nirvana, but to be reborn for as long as other sentient beings remain unliberated by enlightenment.

In Tangier in the late 1950s Burroughs had sunk into an abject stasis of severe addiction. As he wrote in a 1962 forward to Naked Lunch:

I lived in one room in the Native Quarter of Tangier. I had not taken a bath in a year nor changed my clothes or removed them except to stick a needle every hour in the fibrous grey wooden flesh of terminal addiction. I never cleaned or dusted the room. Empty ampule boxes and garbage piled to the ceiling. Light and water long since turned off for non-payment. I did absolutely nothing. I could look at the end of my shoe for eight hours.

In Tangier in the late 1950s William sank into an abject stasis of addiction.

I am not trying to minimize the misguidedness of mistaking an opiate stupor for a transcendental state, but it is undeniable that narcosis facilitates detachment, and Burroughs saw a rough equivalence between the cellular apathy of the stoned junky and the transcendental stillness of the meditator. And in a way, he was sort of on target: “emptying the mind,” which is a preliminary stage in sitting practice, was the goal he was eternally seeking. But the subjective effect of junk is more like “emptying the heart,” that is, numbing painful emotions such as unrequited love, self-loathing and remorse. So again there is a misunderstanding, and a serious contradiction: Burroughs claimed to reject the “purely negative goal” of avoidance of suffering—but what else was he doing by using narcotics?

In Tangier and Paris in the late 1950s, Burroughs’ great friend, the painter Brion Gysin, introduced him to some of L. Ron Hubbard’s earliest disciples: John and Mary Cook, and John McMasters. Later, living in London in the mid-1960s, Burroughs stayed at Hubbard’s Scientology headquarters in East Grinstead; he was trying to “go Clear.” (He was a card-carrying Church member for less than one year). Also at this time Burroughs was impressed by a cognitive system which its proponents called Vipassana, using the Sanskrit word for “mindfulness.” This he understood not just in its simplest form, awareness of one’s own mind, but also with his old tendency to approach enlightenment from his starting-place of self-defense techniques.

From his impressions of this “Vipassana technique” Burroughs evolved a mindfulness methodology of his own, tailored to his solitary life in London during those years: the “Discipline of D.E.,” or “Do Easy.” This was an elaborate (and unintentionally humorous) system for carrying out household chores with a minimum of physical effort. For example:

Colonel Sutton-Smith 65, retired not uncomfortably on a supplementary private income … flat in Bury Street St James … cottage in Wales …

The Colonel Issues Beginners DE

DE is a way of doing. It is a way of doing everything you do. DE simply means doing whatever you do in the easiest most relaxed way you can manage which is also the quickest and most efficient way as you will find as you advance in DE. […]

Never let a poorly executed sequence pass. If you throw a match at a wastebasket and miss get right up and put that match in the wastebasket. If you have time repeat the cast that failed. There is always a reason for missing an easy toss. Repeat toss and you will find it.

Burroughs often wrote about his belief in a ‘magical universe.’ He developed a view of the world that was based primarily on Will: nothing happens unless someone wills it to happen. Curses are real, possession is real.

Burroughs often wrote about his belief in a “magical universe.” He studied anthropology and comparative religions, at Harvard and at Mexico City College, and he developed a view of the world that was based primarily on Will: nothing happens unless someone wills it to happen. Curses are real, possession is real. This struck him in the end as a better model for human experience and psychology than the neurosis theories of Freud. But it also fit neatly into his personal experience of “Self and Other.” For him, the Other was a deadly challenge to the Self, and never worse than when it manifested as “the Other Half,” an Other inside. Eventually he identified the invading entity as “the Word,” and rather than try to explain the rest of that theory, I will just refer you to his books, in particular the Cut-Up trilogy, The Job, and The Adding Machine.

As a self-described “Astronaut of Inner Space,” Burroughs cannot be considered a purely spiritual seeker. He was busy with the world of imagination, of scenes and characters and voices and action. But he did pursue a lifelong quest for spiritual techniques by which to master his unruly thoughts and feelings, to gain a feeling of safety from oppression and assault from without, and from within. The list of liberational systems that he took up and tried is a long one, including: General Semantics; Freudian psychoanalysis, hypnoanalysis, and narcoanalysis; Reich’s orgone box and vegetotherapy; Alexander’s Posture Method; Scientology; est; Silva Mind Control; Robert Monroe’s astral projection; Peter Valentine’s Psychic Self-Defense; etc. (Trungpa Rinpoche wrote about “cutting through spiritual materialism,” critiquing the American tendency to go on a shopping spree in the supermarket of spirituality, and in some ways this applies to William’s quest.)

William Burroughs was an early and longstanding adjunct faculty member with the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, founded in 1975 by Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman. In 1975, at age 61, William was asked by Allen and Anne to come to Naropa and give some classes and readings. William had encountered Trungpa in London in the 1960s, but it was in the summer of 1975 that he became personally acquainted with him. Burroughs had already met a number of advanced spiritual leaders of one kind or another, and I think he already saw himself as one of them, a “holy man” of sorts. So William’s stance towards Trungpa was collegial, with the mutual professional respect accorded by one showman to another—a kind of show-biz camaraderie. And I saw that Trungpa seemed to regard William in a similar light.

Now, you should know that a lot of controversy was caused by some of Trungpa’s behavior, and a lot of American poets and writers were offended by Ginsberg’s embrace of Trungpa as his teacher and his establishment of the Kerouac School under the aegis of Naropa Institute and the Nalanda Foundation in Boulder. The fact that Trungpa smoked cigarettes and drank a lot of alcohol, that he created a force of personal bodyguards called “Vajra Guards” and outfitted them in special quasi-military uniforms, etc., didn’t sit well with some people’s idea of how a spiritual teacher should behave—at least, in America. There were some incidents of confrontation and misunderstandings, such as the notorious Snowmass episode; that story is not worth telling again, but it involved excesses of zealotry by some young “Vajra Guards,” and a stubborn contest of wills between Trungpa and an American poet and his girlfriend, who were perhaps spiritual tourists. “Mistakes were made,” as the saying goes.

But none of these things perturbed William in the slightest. He understood that holy men are eccentric by definition, and that showmanship and personal flair are standard tools in the shaman’s medicine bag. He also had a sort of Taoist feeling that everything happens for its own reasons and one ought not to take such things personally. Trungpa’s “crazy wisdom” appealed to Burroughs, and so did the concept of the “Shambhala Warrior”—after all, Burroughs’ own path since childhood had been the way of the warrior. At this same time, the mid-1970s, William was drawn to the “Don Juan” books of Carlos Castaneda, with their emphasis on the “impeccable warrior” tradition. So there was a natural meeting-ground for the life-history and karma of William and the vajradharma of Tibet.

William understood that holy men are eccentric by definition, and that show-

manship and personal flair are standard tools in the shaman’s medicine bag.

Trungpa invited William to spend a few weeks in solitary retreat at his facility in Barnet, Vermont, called “Tail of the Tiger” (now Karme Choling). But when Trungpa told William he should leave his typewriter at home and do no writing while he was living alone in the little cabin, William rebelled and said that as a writer he could not afford to lose any ideas that might come to him during his retreat, and he would take along at least a notepad. This he did, and his notes from that period were published in 1976 as The Retreat Diaries. This decision shows that William did not subordinate himself in a teacher-student relationship with Trungpa; it also suggests that William did not understand the meditation purpose of a retreat, at least not in the Buddhist sense. Here is what he wrote in his introduction to The Retreat Diaries:

… I am more concerned with writing than I am with any sort of enlightenment, which is often an ever-retreating mirage like the fully analyzed or fully liberated person. I use meditation to get material for writing. I am not concerned with some abstract nirvana. It is exactly the visions and fireworks that are useful for me, exactly what all the masters tell us we should pay as little attention to as possible. […] I sense an underlying dogma here to which I am not willing to submit. The purposes of a Boddhisattva and an artist are different and perhaps not reconcilable. Show me a good Buddhist novelist.

[…] As far as any system goes, I prefer the open-ended, dangerous and unpredictable universe of Don Juan to the closed, predictable karma universe of the Buddhists.

Indeed existence is the cause of suffering, and suffering may be good copy. Don Juan says he is an impeccable warrior and not a master; anyone who is looking for a master should look elsewhere. I am not looking for a master; I am looking for the books.

(William permitted Allen Ginsberg to add a footnote to this: “‘Outside the wheel of conditional karmic existence’ would be the Buddhist equivalent of ‘unpredictable, open-ended.'” William was guilty of “either/or thinking” here, of seeing a false dichotomy between determinism and free will. The concept of karma unifies both views, erasing the superficial contradiction between them.)

“As I have said, William was quite at home in the solitary state, and he spent countless hours alone, meditating in his own way as a matter of course. Perhaps his two weeks in the Vermont cabin were more a change of scene than anything else. The simple life of a cabin retreat appealed to him in another way, too: his childhood memories of summertime visits with his family to primitive resort cabins at Harbor Beach, Michigan and Missoula, Montana stayed with him all his life, and you can find many scenes based on these experiences in his work, particularly in the Red Night trilogy.

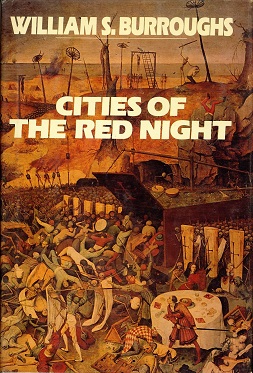

In Cities of the Red Night, which he wrote between 1974 and 1980, there is a chapter called “I Can Take the Hut Set Anywhere,” set in the 19th-century American West. It depicts Burroughs’ teen-aged protagonist and a friend setting up house in a remote location, going to the nearby General Store and stocking up on basic survival goods, etc. This “Hut Set” chapter is the doorway to the next book in the trilogy, The Place of Dead Roads, written between 1977 and 1982. Dead Roads was originally called “The Gay Gun” and it is primarily set in the Old West. The Way of the Gunfighter is a chief preoccupation of the book, and when you know that William did read Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery and similar books in the 1960s, you can see how this examination of the dhyana of marksmanship was a natural evolution of his lifelong study of warriorship, and an organic refinement of his effort to attain “one-pointedness.”

Dead Roads is also very influenced by William’s experiences in Colorado during 1976-1978. For example, the book opens with a pistol duel at the Boulder Cemetery. Now, one of the things that William preferred about Boulder over New York City was that he could go just a little ways out of town and target-practice with pistols to his heart’s content. He could—and did—buy pistols over the counter at a gun store near Pearl Street. William liked to go shooting at our friend Steven Lowe’s cabin in Eldora, in the Foothills, and he was living with Cabell Lee Hardy at Apt. 415 in the old Varsity Manor (which he always called “the Varsity Ma-nór,” at Marine Street and Broadway.

William’s 29-year-old son Billy came to town for Naropa in the summer

of 1976 and immediately collapsed: his liver gave out.

William resided in Boulder from June 1976 through October 1978, although he was only scheduled to spend a week or two in June at the outset. He stayed on because his 29-year-old son, Billy, came to town for Naropa in the summer of 1976 and immediately collapsed: his liver gave out, and this life-and-death crisis worsened for several weeks until Billy was given a new liver in a transplant operation at Denver General Hospital in August 1976. William was very close to everything happening to Billy, and he was with him through many horrific experiences. Anyone who thinks William Burroughs got away scot-free after Joan’s death should have been around Boulder in the summer and fall of 1976, when Billy’s physical, psychological, and spiritual collapse came down hard and right in William’s 62-year-old face.

After fall 1978 William began to divide his time more between Boulder and New York, and in August 1980 he gave up the Varsity Manor apartment and went back to the Bunker in New York. Billy, with his new liver failing, went to Florida in January, and he died there on March 3, 1981. William stayed in New York until Christmas 1981, when he moved to Kansas. He had built up a new heroin habit sometime in 1979 but now he was on methadone. William had visited my Kansas outpost several times, and he decided to retire to Lawrence, a midwestern college town that was much like Boulder in the “golden age,” when there were poetry readings at “Le Bar” in the Boulderado Hotel (where William and I lived in Fall 1976) … the magical days of the mid-1970s in Boulder, before a tsunami of money swept most of that away and turned the town into Colorado’s Santa Fe.

(Even Trungpa left Boulder, in 1986, for Halifax, Nova Scotia—and in the Shambhala website biography of Trungpa, no less, it says he did this “based on his desire to establish the centre of his organization in a less agressive and materialistic atmosphere”—! So I’m not alone in seeing a disadvantageous change in Boulder since the mid-1970s. But we were all much younger then, too. And since Boulder is the home of Naropa, that in itself is auspicious, and we must make the most of it.)

When Billy Burroughs died, it was just as Cities of the Red Night was being published. William had begun writing scenes as early as 1977 that would end up in Dead Roads, but that novel took on a more somber tone as he worked on it after Billy’s death. He finished it during his first year in Lawrence, and once again, there was a long doorway passage letting onto the next and final novel, The Western Lands, which he was inspired to write after reading Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings in the early 1980s.

Billy died just as Cities of the Red Night was being published.

In a two-story, 19th-century stone house south of Lawrence, Kansas, William put the finishing touches on Dead Roads. He could shoot targets in the old barn right behind his house, and he began to make his first “shotgun paintings.” But literarily he had already “done the gunslinger thing” in Dead Roads, and now he focused directly on the question of immortality. Of course he made great sport of the “Egyptian immortality blueprint,” as he called it—the Mummy Road:

“The most arbitrary, precarious and bureaucratic immortality blueprint was drafted by the ancient Egyptians. First you had to get yourself mummified, and that was very expensive, making immortality a monopoly of the truly rich. Then your continued immortality in the Western Lands was entirely dependent on the continued existence of your mummy. That is why they had their mummies guarded by demons and hid good.”

Burroughs’ fascination with his personalized version of the Egyptian concept of “the Seven Souls” demonstrates his deep-seated theism (a universe not of One God but many Gods) and the literalness with which he imagined these deities. His “many gods” have meta-human motivations, like the Lords and Ladies of Mount Olympus—and a similar kind of control over the actions of mortals. One of William’s favorite quotes was from Fitzgerald’s translation of Khayyam: “On this checkerboard of nights and days / Hither and thither moves and checks and slays / And one by one back in the closet lays.”

The “he” in these lines is Death himself, whom William studied as one of the gods—and one with particularly inscrutable motives. “Why does Death want to kill me?” he asked himself. One of William’s great strengths as a writer was closely allied to one of his spiritual weaknesses: a deep strain of solipsism. By taking Death’s onslaught personally, he was distracted from considering the broader approach, that all things pass away—lakshana, the Second Mark of all conditioned dharmas. That is, William understood this phenomenon intellectually, but not in his heart; at least, not until his final years.

Burroughs did instinctively believe in reincarnation.

(Just as a side note, it would be interesting to compare-and-contrast Burroughs’ interpretation of the Egyptian Seven Souls to various Buddhist models. As an animist, seeing will and intention in all living entities, William did not take to the concept of anatman, or the essential voidness of Self (i.e., the Third Mark). But his Seven Souls can be compared to the five Skandhas of personality, and his concept of the departure of the Souls, one by one at the moment of death, can be considered in parallel with the descriptions found in the Bardo Thodol, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which he read and referred to at times.)

Burroughs did instinctively believe in reincarnation; as he wrote in a key passage of Dead Roads: “Kim has never doubted the possibility of an afterlife or the existence of gods. In fact he intends to become a god, to shoot his way to immortality, to invent his way, to write his way.”

In Cities William wrote about the “Transmigrants,” adepts who underwent ritual suicide at a young age after careful training so they could select their next incarnation at will. “Death is a landing field,” as he wrote in 1975 in the introduction to his novella, Ah Pook Is Here (Ah Pook incidentally being the Mayan God of Death):

If you see reincarnation as a fact then the question arises: how does one orient oneself with regard to future lives? Consider death as a dangerous journey in which all past mistakes will count against you. If you are not orienting yourself on sound factual data, you will not arrive at your destination or in some cases you may arrive in fragments. What basic principles can be set forth? Perhaps the most important is relaxed alertness, and this is the point of the martial arts and other systems of spiritual training—to inculcate a psychic and physical stance of alert passivity and focused attention. Suspicion, fear, self-assertion, rigid preconceptions of right and wrong, shrinking and flinching from what may seem monstrous in human terms—such attitudes of mind and body are disastrous. See yourself as the pilot of an elaborate spacecraft in unfamiliar territory. If you freeze, tense up, refuse to look at what is in front of you, you will crack up the ship. On the other hand, credulity and uncritical receptivity are almost as dangerous.

Your death is an organism which you yourself create. If you fear it or prostrate yourself before it, the organism becomes your master. Death is also a protean organism that never repeats itself word for word. It must always present the face of surprised recognition. For this reason I consider the Egyptian and Tibetan books of the dead, with their emphasis on ritual and knowing the right words, totally inadequate. There are no right words. Death is a forced landing, in many cases a parachute jump.

‘There are no right words. Death is a forced landing, in many cases a parachute jump.’ — Burroughs, Ah Pook

But at that time, the 1970s, William visualized rebirth as a challenge, not a threat. His Transmigrants wanted to be reborn, so they could re-experience the magical period of childhood and the sexual intensity of adolescence. These youths are not exactly held up as a model, however, and we may observe that William had already spent a decade working with that sexual material in his writing, in Wild Boys for example—re-running sexually potent scenes over and over, as in a film loop or a Scientology auditing session, in an effort to neutralize the power he felt these scenes had over him. So again he was—after all—seeking the “cessation of suffering” (Third Noble Truth) by way of the extinction of craving. And in the 1980s he had the assistance of old age and methadone maintenance to help him leave behind the first of the Three Fires that are obstacles to enlightenment, i.e., lust.

Billy’s death and William’s move to the Midwest prepared the ground for William Burroughs’ bodhi, the awakening of his tender heart to the limitless field of compassion, and the vector of this awakening in his life arrived in the form of … cats. By the time Western Lands was published in 1987, William had become a dedicated cat-lover, with a household full of animals. His cat-inspired meditations can be found in the last part of Western Lands and, of course, in The Cat Inside, where he wrote:

My relationship with my cats has saved me from a deadly, pervasive ignorance. […]

I have said that cats serve as Familiars, psychic companions. […] The Familiars of an old writer are his memories, scenes and characters from his past, real or imaginary. A psychoanalyst would say I am simply projecting these fantasies onto my cats. Yes, quite simply and quite literally cats serve as sensitive screens for quite precise attitudes when cast in appropriate roles. The roles can shift and one cat may take various parts: my mother; my wife, Joan; Jane Bowles; my son, Billy; my father; Kiki and other amigos; Denton Welch, who has influenced me more than any other writer, though we never met. Cats may be my last living link to a dying species. […]

This cat book is an allegory, in which the writer’s past life is presented to him in a cat charade. Not that the cats are puppets. Far from it. They are living, breathing creatures, and when any other being is contacted, it is sad: because you see the limitations, the pain and fear and the final death. That is what contact means. That is what I see when I touch a cat and find that tears are flowing down my face.

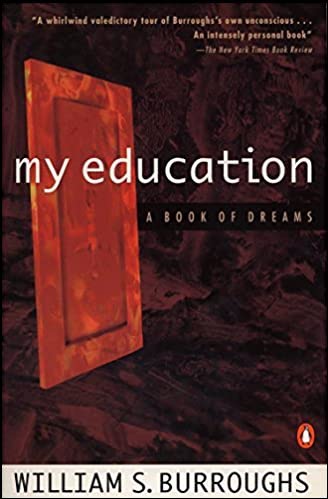

In Western Lands, and even more so in My Education: A Book of Dreams, William encounters most of his old friends in the “L.O.D.”—the Land of the Dead, which is coterminous with the world of his dreams.

In the mid-1980s William went through a period of deep sadness and depression, reviewing a life’s catalog of mistakes and regrets, and this seems to have resulted in a kind of spiritual awakening, because by the end of his life ten years later he really had become enormously sweet and tender-hearted. I don’t mean saccharine-sweet—William was salty and irreverent and funny to the end—but he was more patient, more kindly, more considerate, more grateful, and more gracious. I would say he was trying to extinguish the Second Fire, ill-will, and to stave off the onset of the Third, mental dullness or boredom. In Western Lands, and even more so in My Education: A Book of Dreams (which he assembled in the early 1990s), he encounters most of his old friends in the “L.O.D.”—the Land of the Dead, which in turn is coterminous with the world of his dreams, meaning that his view of the afterlife is a life in dreams, or a bardo state, between lives.

As death approached, William was writing in what he knew would be his final journals. In these he wrestled with his anger at man’s bottomless ignorance, and seems to have overcome it to a large extent, by the end. I think he never stopped believing that, in the words of Sri Aurobindo, which he often quoted: “This is a War Universe”—and he always saw himself in the warrior’s role. But by some dispensation of his own curious karma, including all the social and historical baggage he was born with, and all the passions he felt and violent actions he took in his life, William Burroughs was given a final decade of old age in which to look back upon that life and study its lessons—and in this time, with the help of his beloved cats, he attained a state of ahimsa, compassion for the suffering that is everywhere.

I’d like to close with these lines from The Place of Dead Roads:

“‘Whenever you use this bow I will be there,’ the Zen archery master tells his students. And he means there quite literally. He lives in his students and thus achieves a measure of immortality. And the immortality of a writer is to be taken literally. Whenever anyone reads his words the writer is there. He lives in his readers.” •

+++

“Burroughs and the Dharma” copyright © 1999 by James Grauerholz, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC. “Burroughs and the Dharma” was collected in CIVIL DISOBEDIENCES, edited by Anne Waldman and Lisa Birman, and published by Coffee House Press, 2004.

William’s great contributions were in the 1960’s – the great cut up works, his scrapbooks and tape experiments. Post 1984 works simply didn’t work.

Great piece with an unexpected angle on Burroughs. I remember reading Last Words for the first time and being puzzled by WSB expressing belief in God. A piece like this really contextualizes it.

While personally I prefer Burroughs’ writings up to about the time he returned to America, I have to say there are people I respect who’ve expressed admiration for the late trilogy — Carl Weissner prime among them.

I suppose I could add “as powerfully” to the end of my comment to be polite.

Carl’s taste was impeccable. I myself liked ‘Dead Roads’ for its personal intimacies.