It’s from an old-fashioned translation, but you get the picture.

His Life, the biography

by Théophile Gautier

[Trans. by Guy Thorne]

“He did not believe that men were born good, and he admitted original perversity as an element to be found in the depths of the purest souls—perversity, that evil counsellor who leads a man on to do what is fatal to himself precisely because it is fatal and for the pleasure of acting contrary to law, without other attraction than disobedience, outside of sensuality, profit, or charm. This perversity he believes to be in others as in himself. ...

poet, journalist, novelist,

dramatist, and art critic

“He hated evil as a mathematical deviation, and, in his quality of a perfect gentleman, he scorned it as unseemly, ridiculous, bourgeois and squalid. If he has often treated of hideous, repugnant, and unhealthy subjects, it is from that horror and fascination which makes the magnetized bird go down into the unclean mouth of the serpent; but more than once, with a vigorous flap of his wings, he breaks the charm and flies upwards to bluer and more spiritual regions.

“If his bouquet is composed of strange flowers, of metallic colorings and exotic perfumes, the calyx of which, instead of joy contains bitter tears and drops of aqua tofana, he can reply that he planted but a few into the black soil, saturating them in putrefaction, as the soil of a cemetery dissolves the corpses of preceding centuries among mephitic miasmas. Undoubtedly roses, marguerites, violets, are the more agreeable spring flowers; but he thinks little of them in the black mud with which the pavements of the town are covered.

As much as possible he banished from poetry

a too realistic imitation of eloquence, passion, and a too exact truth.

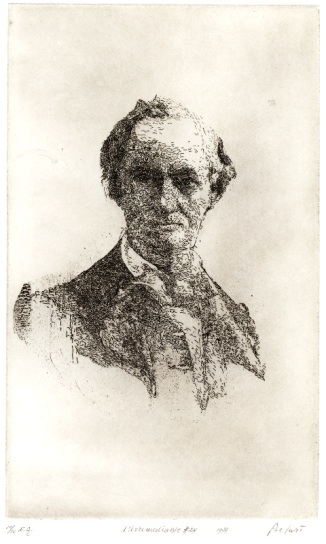

Etching © 1977 by Gerard Bellaart

“He likes to follow the pale, shrivelled, contorted man, convulsed by passions, and actual modern ennui, through the sinuosities of that great madrepore of Paris—to surprise him in his difficulties, agonies, miseries, prostrations, and excitements, his nervousness and despair. He watches the budding of evil instincts, the ignoble habits idly acquired in degradation. And, from this sight which attracts and repels him, he becomes incurably melancholy; for he thinks himself no better than others, and allows the pure arc of the heavens and the brilliancy of the stars to be veiled by impure mists.

“With these ideas one can well understand that Baudelaire believed in the absolute self-government of art, and that he would not admit that poetry should have any end outside itself, or any mission to fulfill other than that of exciting in the soul of the reader the sensation of supreme beauty—beauty in the absolute sense of the term. To this sensation he liked to add a certain effect of surprise, astonishment, and rarity. As much as possible he banished from poetry a too realistic imitation of eloquence, passion, and a too exact truth. As in statuary one does not mould forms directly after Nature, so he wished that, before entering the sphere of Art, each object should be subjected to a metamorphosis that would adapt it to this subtle medium, idealising it and abstracting it from trivial reality.

“Depravity—that is to say, a step aside from the normal type—is impossible to the stupid. It is for the same reason that inspired poets, not having the control and direction of their works, caused him a sort of aversion, and why he wished to introduce art and technique even into originality.

“So much for the metaphysical; but Baudelaire was of a subtle, complicated, reasoning, and paradoxical nature, and had more philosophy than is general amongst poets. The æsthetics of his art occupied him much; he abounded in systems which he tried to realise, and all that he did was first planned out. According to him, literature ought to be intentional, and the accidental restrained as much as possible. This, however, did not prevent him, in true poetical fashion, from profiting by the happy chances of executing those beauties which burst forth suddenly without premeditation, like the little flowers accidentally mixed with the grain chosen by the sower. Every artist is somewhat like Lope de Vega, who, at the moment of the composition of his comedies, locked up his precepts under six keys—con seis claves. In the ardour of his work, voluntarily or not, he forgot systems and paradoxes.”