‘To describe human misery in all its vastness and

intensity without creating an air of disqualification.

To trim misery of petulance and morbidity,

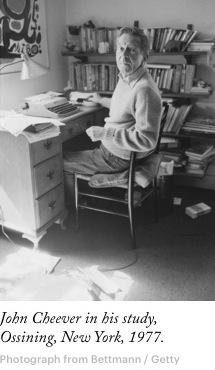

to give pain some nobility.’ – John Cheever

Journal excerpts from ‘The Sixties’

What has gone wrong, that we should all seem to be made of paper and straw? What is the world I wish to achieve for myself and my sons? What would be a better scene for this discourse? God knows. A mountain pass, a long beach, the darkness just before a storm.

To disguise nothing, to conceal nothing, to write about those things that are closest to our pain, our happiness; to write about my sexual clumsiness, the agonies of Tantalus, the depth of my discouragement—I seem to glimpse it in my dreams—my despair. To write about the foolish agonies of anxiety, the refreshment of our strength when these are ended; to write about our painful search for self, jeopardized by a stranger in the post office, a half-seen face in a train window; to write about the continents and populations of our dreams, about love and death, good and evil, the end of the world.

I make no headway, and yet it seems best to come here every day and try. It is not easy. I have had winters before and will have them again, and do not seriously doubt that they will end—the winters—but it is not easy. I am reminded of the weeks and months in Rome when I saw nothing with the right eyes but a cobweb gleaming in the sunlight and an owl flying out of a ruin. Thinking of X, who was tyrannized by a fable of herculean sexual prowess but who was, like the rest of us, clay.

A warm day; we lunch on the outside steps

and my old dick stirs in the sunlight like a hyacinth.

Later, in the warmth, taking away wheelbarrow-loads of dead leaves, I am suddenly very tired. I move slowly and painfully, like an old man. Pain seems like a rivet put through my chest into my back. Then I think that I shall not live to see the spring; I shall soon die. “John is dead, he died quite suddenly. Do try to get to the church early. We are so afraid there won’t be room.” My muffled voice rises from the casket: “But I haven’t finished my work. My seven novels, my two plays, and the libretto for an opera. It isn’t done.” The priest tells me to be still. Preparations are made for a crowd, but on the big day the telephone begins to ring: “It’s Binxie’s only chance to play golf. We’re sure John would understand. He was always so carefree.” “It’s Mabel’s only chance to go shopping.” Etc. In the end no one comes. I see the disgusting morbidity of all this, I try to cleanse my mind. If we do not taste death, how will we know the winter from the spring? I paint shutters, cut a little wood, light a fire. The clear light of the fire is appealing; this, and the sound of water, is what I want.

Let us pray for all of those killed or cruelly wounded on throughways, expressways, freeways, and turnpikes. Let us pray for all of those burned or otherwise extinguished in faulty plane landings, midair collisions, and mountainside crashes. Let us pray for all alcoholics measuring out the hours of the day that the Lord hath made in pints and fifths, and let us pray for the man who mistook a shirt button for a Miltown pill and choked to death in a hotel.

A brilliant autumn day. Searching lights. Many vapor trails drawn high, due north. Are these warriors or businessmen eating butterfly shrimp off plastic trays? Is this the end of the earth or a bond to keep it from ending? Hot and cold, brilliance and darkness, the afterglow as fine as anything seen in the mountains; but X, studying the stars, would find in this wall of brilliance a reflection of his own emotional vacuity.

I have not repaired the shutter on the west window. I have not got sand for the driveway or mixed fuel for the chain saw. I have not taken my clothes to the dry cleaner’s. Cutting into the roast and finding it underdone I have, without saying a word, been able to accomplish a devastating emanation of disgust and disapproval. Serving the flounder I have, by way of petulance, helped the family generously and given myself a boiled potato and a spoonful of grease. I have unjustly accused my wife of unfaithfulness, and called my only and beloved daughter plain and friendless to her face. I have been drunken, dirty, unkind, embittered, and lewd.

It is not the facts that we can put our fingers on which concern us but the sum of these facts; it is not the data we want but the essence of the data. It is the momentary and overwhelming sense of pathos we experience when we see the congregation turn away clumsily from the chancel; the encouragement we experience when we hear the noise of a stamping mill carried over water; the disturbance we feel when we see misgiving in a child’s face. She is carrying schoolbooks and waiting for the traffic light to change. The carnal and hearty smell of bilge water, the smell of must in the cold pantries of this old house. A continent of feeling lies beyond these. We call them apprehensions, but they have more fact, truth, illumination than the wastebasket, the gunrack, and the cheese knife. Why be afraid of madness? Here is a world to win, to discover.