West Yorkshire, U.K.

Asa, translucent Jew,

your eyebrows arched

so high as to hold

nothing excluded that might want in,

it's proper to come your way

by deflection. Exquisite poet . . .

— Roy Fisher

The American “Poets Corner”

on the edge of West Yorkshire Moors

By JAY JEFF JONES

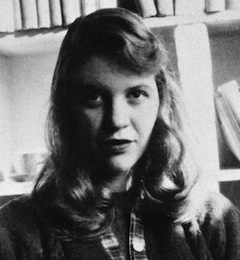

It’s unlikely that Sylvia Plath would have picked the graveyard of Heptonstall Church for her last resting place. Early in her marriage to Ted Hughes, she declined the suggestion that they move into some cheap and rambling old manor in the socially depressed Calder Valley. This was where the most formative part of Hughes’ childhood had been spent. They had this discussion at the bar of a dingy public house called The Stubbing Wharf and, in the poem he wrote about the occasion, Hughes evoked a mood of “shut-in sodden dreariness”. The pub had already appeared in a short story he had published, a boyhood recollection of Sunday lunchtime, when the locals took grim delight in setting terriers onto captured rats.

One of the properties he had in mind for a marital home was Lumb Bank, located down the hill from The Beacon, a moortop house on the edge of Heptonstall village where Hughes’ parents lived. In damp weather, the Lumb Valley wasn’t that cheerful either; it could be easily cut off in the winters and there were stories that the long-drop waterfall at the bottom of the valley was haunted by the ghosts of dead babies. Plath was pregnant and homesick at this time and it wasn’t as if she didn’t have enough emotional baggage already. Hughes’ poetic account paints a picture of a gloomy lost world of defunct mills and abandoned chapels, a valley that’s the “fallen-in grave of its history.” In spite of that, Plath’s trips to Heptonstall, mostly to visits Hughes’ family, were woven into her poetry. She once referred to it as a “dream-peopled village” and that, “The whole landscape / loomed absolute as the antique world was / once…”.

Asa Benveniste definitely chose the location of his own grave, having spent the final years of his life in Hebden Bridge, the valley town that adjoins Heptonstall. It was a place he discovered as a result of leading a course at the Arvon Foundation, a charity that organises writing courses and retreats. Oddly enough the course ran at Lumb Bank, the same rambling mill owner’s house that Hughes considered as a possible home for Plath and himself. He had bought the place anyway as an alternative to his main residence in Devon, and offered its use to Arvon as a northern residential centre in 1975.

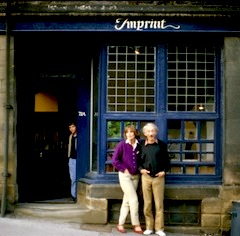

Asa moved north after years of living in London, where he (and wife Pip) had founded the Trigram Press in 1965. This was the same year that the International Poetry Incarnation was held at the Albert Hall, an event that galvanised London’s underground culture and energetically intersected the Beat and post-Beat poets of America and Britain. From this international network came most of the material for Trigram’s publications and two other independent artisan presses launched that same year, Fulcrum and Goliard. Asa also wrote his own poems and ultimately produced seven solo collections. After semi-retiring from publishing, he and Agnetha Falk set up a house/bookshop in Hebden Bridge stocked mostly with the library he had collected over the years. He would look up in alarm as customers arrived through the shop door and watch them leave, carrying purchases, with resignation. On the day he jokingly enacted Kilroy on Plath’s headstone (photographed by Alistair Johnstone of the Poltroon Press), he had no idea how few years would pass before he became Plath’s permanent neighbour under the soil.

The hundreds of Plath-seeking visitors to the graveyard every year have eyes for no one but her of course; very few know about Asa or seek him out. Before he died, he lost a leg to diabetes and in his last small collection conflated that and the approaching end of life with the amputated Rimbaud. “He writes poems without / one excess adjective / his language / which is pure prose. / Phantom pain. / Invisible ink.”

Of the visitors coming to spend a moment with Plath, Patti Smith has been at least three times. Hearing that she is a frequenter of other literary graves, I assumed those of the sainted Beat trio, but certainly she paid her respects to Jim Morrison, Anne Bronte, Bertolt Brecht, Genet and, of course, Rimbaud. It’s there she was snapped gavotting across the marble monument like a vagrant memorial angel at the afterlife disco.

By fortunate coincidence I came across a sharp and swinging poem, “Recent boring literary pastimes” by Diane di Prima, which includes –

“Eating yr words / eating yr hat / eating the wet hat of a dead poet / in a cemetery full of dismembered freezers / remembering the 40s / remembering the samba / remember rubbing elbows w/ obnoxious dead / poets in filthy bars in unmentionable / neighbourhoods…”