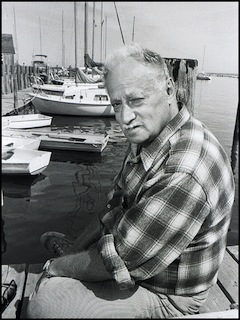

In a rave review of what he calls a “vastly insightful” biography of Nelson Algren, Andrew O’Hagan sums up his admiration for Algren this way:

More than Walt Whitman or John Steinbeck, more than F. Scott Fitzgerald or Dorothy Parker, he reveals the essential loneliness of the serious writer, never fooling himself with baubles and status, but staying with his subjects, the forgotten in society and his own alien self.”

In paragraph after paragraph, O’Hagan describes not only what made Algren a shamefully unsung master who deserves recognition among the greats of the modern American literary canon but also why he was denied it.

The New York intellectuals didn’t love him, and what they admired in E.M. Forster or Henry James they loathed in Nelson Algren: his social intelligence, the dark, organic wealth of his perception. His shirt collar was simply too frayed for the likes of Lionel Trilling. Algren countered with Zola and Chekhov. “The business of writers is not to accuse,” he quoted from the latter, “not to persecute, but to side even with the guilty, once they are condemned and suffer punishment.”

I could go on quoting at length from O’Hagan’s review because it offers one gem after another. Here is just a taste:

Fame didn’t suit him, money was scarce, love left him lonely, and his publisher would eventually walk away from him, refusing to publish his excoriating essay Nonconformity, and later taking a pass on his novel A Walk on the Wild Side. He called himself “the tin whistle of American letters,” while knowing he was a “platinum saxophone.” . . .

. . . [H]e was always liable to suffer for the depth and constancy of his identification with the deprived, just as Fitzgerald suffered from too much identification with the swells. Kurt Vonnegut called him “the loneliest man I ever knew,” and the move toward exile—as for Samuel Beckett—was a natural-seeming one, kindling to the work if hard on the soul. . . .

. . . [H]is style rises, quite separately, from a moral acuity about the real substance of the United States. He caught it on the wind, the half-empty, half-bustling sound that blows through the stories of Jack London; the same one that whistles through the songs of Woody Guthrie and provides the grace notes in Fitzgerald, and he married that music to a sociological interest in the people of Chicago. For Algren, a tireless reporter’s job had to be done on the people he saw every day, but he didn’t stop there: he reimagined their world as poetic literature, a form of high-style witnessing. He liked to quote Conrad: “A novelist who would think himself of a superior essence to other men would miss the first condition of his calling.” That’s the Algren hallmark. He lived at the center of his material.