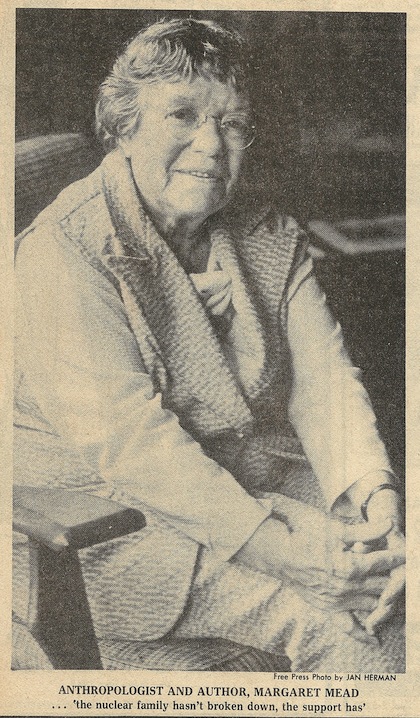

Alison Gopnick has a nicely done piece in The Atlantic about a new book that explores “the students of sex and culture”—namely Margaret Mead, Ruth Benedict, and Zora Neale Hurston—who “revolutionized the way we think about humanity.” The book by Charles King, Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century, has been getting lots of attention. Which reminds me that in my antideluvian days, when I was starting out as a reporter for the Burlington Free Press, I interviewed Mead. She was summering in East Craftsbury, northern Vermont, at a colleague’s home. I didn’t know much about her beyond the usual, so my interview hardly went beyond the usual. What I remember most was the photo I took of her and how smitten I was by her graciousness.

“So what shall we talk about?” she said. Naturally I asked about one of her lifelong concerns: family and child rearing. Her remarks still seem pertinent.

“Everybody says the nuclear family is dead. It isn’t,” she said. “The nuclear family hasn’t broken down. It’s the support system that has. There is nothing in the world wrong with the nuclear family if it lives in a decent community. But the isolated American family, living as it does in a tract house somewhere, is not very promising.”

She attributed the breakdown to poor town planning that grew out of the post-World War II era, when families began to flee the inner cities for the doubtful splendors of suburbia.

“Everybody was saying, ‘Aren’t cities awful! Let’s take the children out of them.’ That’s when everybody wanted a home and a lawn they could call their own. Now kids are brought up in segregated suburbs where they never get the chance to see anybody but other kids just like themselves.

“We shouldn’t go backwards, but we should have kept more of a variegated pattern of living. The town planning we’ve done so far has wrecked this country. It has wrecked the inner cities and it has condemned vast numbers of people to isolation with no plan for children. Then we’re surprised when kids become destructive and turn into vandals. Everybody loses with the present system, and it’s not only the kids.”

Child abuse was in the news then, just as it is now. Mead’s take on the subject was that “child abuse is not really abuse. It’s a parent’s frantic cry for help. So what do we do? We take kids away and put them in places that are not fit for them. Meanwhile the parents are not allowed to solved their problem.”

The solution, she said, was to establish “new family forms” as ancient as some of the tribal patterns she had studied in the 1920s. “If you have something good from the past, for God’s sake keep it. I’m not talking only about the United States, but about families everywhere. I’ve been saying this for 40 years, ever since I came back from Samoa, where I watched families live with very big households and large numbers of supports.

“This doesn’t mean putting mother-in-law back in the house,” she said. “But everybody would be happy to have mother-in-law or grandma about a block away. It functions like part of an equation. If the mother has an extended family around to help her, she wouldn’t be so overwhelmed.”

My next question was the usual one about parenting: Is it better to be permissive or authoritarian?

“That’s not the choice,” she said. “Why are we always looking for polarities? We ought to take the third alternative—tough democracy. There are occasions when people have to give orders that must be obeyed at once.”

She also pointed out that violence among children was not something to be ruled off limits. Societies which teach children to abhor violence, she said, paradoxically turn out to be the most violent.

“In places like England, which is one of the least violent societies, children learn that fighting is acceptable at certain times. But in America, mothers teach kids when to fight and when not to, and that’s not a very good thing. Mothers don’t know anything about fighting.”

As for competitiveness, it’s a good thing. “After all, ” she remarked, “that’s what kept England afloat during World War I. It’s said the war was won on the playing fields of Eton. Well, that’s true, if you take away the Eton.”

She would have made a great interview for Bill Maher.

Great recollection of a wise and sorely missed woman. By the way many of those English playing fields have been sold off now, excepting the ones at Eton, of course.