Aaron Shulman’s collective biography of the Spanish Panero family, The Age of Disenchanments—just out from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins— has a cast of dramatic characters that is nothing less than stunning. As I’ve previously written:

“The family patriarch was the poet laureate of the Franco regime, Leopoldo Panero, who betrayed the ideals of his friend Federico García Lorca during the Spanish Civil War (and later battled with the Chilean poet and Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda).”

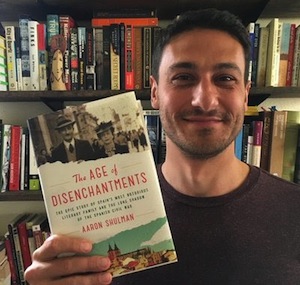

The Age of Disenchantments

“No one’s ever told their story in English, and only in fragments in Spanish,” Shulman says.

As he has written in The Believer, “the Paneros are the stuff of fiction, which is the best type of reality: the kind that humbles the imagination of novelists but doesn’t deter them from trying.”

The matriarch of the family was Felicidad (Blanc) Panero, an actress and writer (and obsessive stage manager of the family legacy). Their three sons were also poets — most significantly the subversive Leopoldo María Panero, who would spend the 1980s living in a mental institution and whose poetry readings drew mobs of fans. Roberto Bolaño considered him a genius, and in the last interview he gave before his death, in 2003, called him “one of the three best living poets in Spain.”

Shulman tells the story with great style. He offers the kind of intimate details which bring his subjects to life in prose that is a pleasure to read. Here’s a taste from the opening of the prologue to the book.

Before dawn on August 17, 1936, a man dressed in white pajamas and a blazer stepped out of a car onto the dirt road connecting the towns of Viznar and Alfacar in the foothills outside Granada, Spain. He had thick, arching eyebrows, a widow’s peak sharpened by a tar-black receding hairline, and a slight gut that looked good on his thirty-eight-year-old frame.

It was a moonless night and he wasn’t alone under the dark tent of the Andalusian sky. He was escorted by five soldiers, along with three other prisoners: two anarchist bullfighters and a white-haired schoolteacher with a wooden leg. The headlights from the two cars that had delivered them here illuminated the group as they made their way over an embankment onto a nearby field dotted with olive trees. The soldiers carried Astra 900 semiautomatic pistols and German Mauser rifles. By now the four captives knew that they were going to die. The man in the pajamas was the poet Federico García Lorca.

You can’t get more novelistic than that. Yet Shulman is scrupulous about being factual. That is evident from cover to cover. It makes The Age of Disenchantments a terrific read.