Of all the heavy bombers that saw action during the Second World War, none earned as much admiration, gratitude, and affection from their crews as the B-17. It was durable, maneuverable, easy to fly. It was fast for its size and well-armed. It could bring you back alive even with its tail shot off, or with gaping holes blown in a wing, or with three of its four engines out and a fuselage ripped by hundreds of bullets. It could cruise six miles above the ground, beyond sight of the naked eye. It could dive at speeds of more than four hundred miles per hour and was known to do complete loops without tearing off its wings.

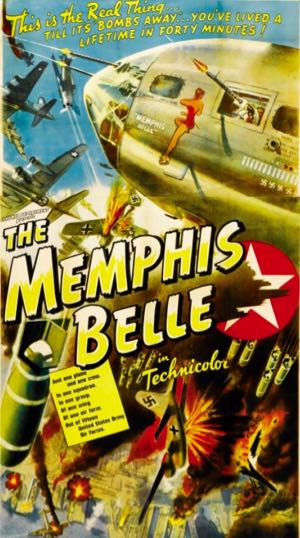

NY FILM FESTIVAL REMINDER: A newly restored print of William Wyler’s World War II air-combat documentary “The Memphis Belle” and Erik Nelson’s new documentary “The Cold Blue” (created from recently discovered raw footage shot during the filming of “Memphis Belle”) are to be featured in screenings on Saturday and Sunday (Sept. 29 and 30) at the 56th New York Film Festival.

Dubbed the “Flying Fortress” by a reporter back in 1937, when an early model was being tested, the B-17 carried a ten-man crew: pilot, co-pilot, navigator, radio operator, bombardier, engineer doubling as top-turret gunner, tail gunner, two waist gunners, and a ball-turret gunner. It was a loud plane, primitive in its amenities. The noise of four Wright Cyclone engines, each throbbing with twelve hundred horsepower, made conversation impossible except on the radio intercom. The Plexiglas nose gave the pilots and bombardier a wraparound view of the huge sky above and the ground laid out below. The fuselage, which looked from the inside like an empty metal drum, had a thin catwalk running lengthwise above the bomb bay. The plane was not pressurized. When it flew above ten thousand feet, the crew needed walk-around oxygen bottles. At higher altitudes they worked in subzero temperatures that fell to sixty below. On bombing raids lasting anywhere from three to nine hours frostbite was not uncommon.

Dubbed the “Flying Fortress” by a reporter back in 1937, when an early model was being tested, the B-17 carried a ten-man crew: pilot, co-pilot, navigator, radio operator, bombardier, engineer doubling as top-turret gunner, tail gunner, two waist gunners, and a ball-turret gunner. It was a loud plane, primitive in its amenities. The noise of four Wright Cyclone engines, each throbbing with twelve hundred horsepower, made conversation impossible except on the radio intercom. The Plexiglas nose gave the pilots and bombardier a wraparound view of the huge sky above and the ground laid out below. The fuselage, which looked from the inside like an empty metal drum, had a thin catwalk running lengthwise above the bomb bay. The plane was not pressurized. When it flew above ten thousand feet, the crew needed walk-around oxygen bottles. At higher altitudes they worked in subzero temperatures that fell to sixty below. On bombing raids lasting anywhere from three to nine hours frostbite was not uncommon.

The crew of the “Memphis Belle” after their 25th mission: (l to r) TSgt. Harold Loch (top turret gunner/engineer), SSg.t Cecil Scott (ball turret gunner), TSgt. Robert Hanson (radio operator), Capt. James Verinis (copilot), Capt. Robert Morgan (pilot), Capt. Charles Leighton (navigator), SSgt. John Quinlan (tail gunner), SSgt. Casimer Nastal (waist gunner), Capt. Vincent Evans (bombardier), and SSgt. Clarence Winchell (waist gunner). (U.S. Air Force photo)

The Germans at first were not impressed by the Flying Fortresses, at least not when the British were flying them before the American entry into the war. No single bomber could defend itself against a concerted fighter attack. Though it bristled with fifty-caliber machine guns — ten in all, making it the most heavily armed bomber until then — the B-17 needed to follow certain tactical rules for protection against fighters. The main rule was to fly in tight formations, with enough B-17s grouped together to create a wall of overlapping machine-gun fire in all directions. The British sent their B-17s on daylight bombing raids in twos and threes, not enough to keep from being picked off by swarming Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs. It wasn’t long before the Germans took to calling the new American bombers “Flying Coffins.”

William Wyler (center) with cameramen William Skall (top), William Clothier (right) and British war correspondent Cavo Chin (left).

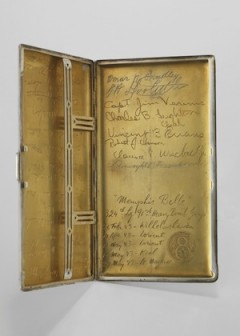

Willy Wyler’s WWII cigarette case

(signed by five crew members of the Memphis Belle, and also by Generals Omar Bradley, "Jimmy" Doolittle, and Dwight Eisenhower). Click to enlarge.

To the bombardier Vincent Evans, Wyler looked like “this over-age major” who didn’t seem fearful of anything. He marveled that Wyler kept “walking the open catwalk of the bomb bay five miles above Germany, breathing out of a walk-around oxygen bottle.” The major, in a bulky flight suit for insulation againt the forty-five-below temperature, kept pointing his hand-held camera at the flak bursts, then at the German fighters, which were trying to break up the formations. “We could hear him cuss over the intercom,” Evans recalled. “By the time he’d swing his camera over to a flak burst, it was lost. Then he’d see another burst, try to get it, miss, see another, try that, miss, try, miss. Then we’d hear him over the intercom, asking if [Morgan] couldn’t possibly get the plane closer to the flak.” Evans couldn’t believe it.

When the bomber groups returned to their bases around two in the afternoon, roughly six hours after takeoff, the casualties were tallied. Seven planes didn’t come back at all, the worst losses for a single day until then. Forty-one men — the equivalent of four full combat crews — were wounded in the Ninety-first alone.

Text excerpted from A Talent for Trouble, the Life of Hollywood Director William Wyler. The screenings will be accompanied by interviews with “The Cold Blue” director Erik Nelson and Catherine Wyler, co-producer of the 1986 American Masters documentary about her father “Directed By William Wyler.”