![Carl Weissner [Photo by Michael Montfort] 'Always These Nightmares'](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Carl-Weissner-foto-by-Michael-Montfort-200-e1506434584640.jpg) In a tribute to the late German author Carl Weissner, who wrote experimental fiction in both English and German in addition to translating more than 100 books by dissident American and British authors, the literary scholar Tomasz Stompor delivered a paper on Weissner’s novel, Death in Paris, at a recent meeting of the European Beat Studies Network. Here it is:

In a tribute to the late German author Carl Weissner, who wrote experimental fiction in both English and German in addition to translating more than 100 books by dissident American and British authors, the literary scholar Tomasz Stompor delivered a paper on Weissner’s novel, Death in Paris, at a recent meeting of the European Beat Studies Network. Here it is:

by Tomasz Stompor

Placed within the thematic focus of this year’s conference “collaboration, publication, translation,” Weissner’s novel Death in Paris deserves a closer look as it offers valuable insight into the complexities of reconciling the position of a translator with that of an author. Death in Paris was first published on realitystudio.org in 2009, and again posthumously in the summer of 2012 as a print edition Weissner began working on the text in 2007 in a blog entitled “The cutting floor” to which he invited a few select friends. (Seward and Herman in: Weissner 2012, 165, 169) Although the title of the blog might suggest the use of cutups in the book, evidence thereof is scant. The title might rather refer to the fragmentary character of the text itself. Even though contributions from participants of this experiment appeared on the blog, it was finally only Weissner’s texts that made it into the book. Given the unavailability of the blog, one can only speculate on the degree to which this sort of collaboration gave Weissner leads and ideas on how to fit the parts into a whole.

Doll No Mori Publishers, 2012 (paperback)

Gerald Lake himself has problems keeping fact and fiction apart as he admits on various occasions: “Alain, or is it his other self, tries to convince himself that he’s turned in a flawless performance so far, professional, not a second of indecision…” (80), or later: “The salty drops of sweat falling from the tip of his nose splatter on the pages of Alain’s notebook […]” (121)

The borderline between literary imagination and factuality was certainly a known field of operations for Weissner as a translator, and the workload he dealt with must have been huge, considering his output. The creative effort invested in the act of translation is undisputed, as is the success of Weissner’s work in this sphere. Charles Bukowski, for example, would never have attained his large readership in Europe without Weissner’s translations and efforts to promote him. But bearing in mind Weissner’s early cutup publications, the writer was still in him and was struggling to come out. In an interview for the German weekly Die Zeit from 2010, Weissner recalled a word of advice he received from Burroughs to keep writing his own texts in between translations or else he would go insane. (Weissner in: Schäfer 2010) One could say that with Death in Paris the writer came out and went on a rampage.

Of course, Weissner profited substantially from the work as a translator. In the same interview he names Burroughs, Bukowski and Ballard as his main influences. But instead of being a creative medium of transmission as a translator, his own writing offered freedom. No matter how trite this statement might sound, I believe that therein lies one key to understanding Weissner’s first literary text after a long hiatus as a writer. I dare to argue that the conflict between the writer and the translator can be transposed to the novel’s protagonist Gerald Lake. His consciousness of the crimes he writes and the ones he commits is foggy to say the least. Similarly, Weissner must have been confronted with the question: To what degree are his translations his own? Or in other words: To what degree is he the author in a prescripted text? Death in Paris demonstrates vividly that the emancipatory act of creative release was for Weissner a violent affair.

One could say the writer came out and went on a rampage.

* * *

Upon reading Death in Paris for the first time, I was struck by the omnipresent and multiform violence in the text, whether casual or monstrous. The dense body count and the graphic descriptions of lives being taken might be interpreted as a tongue-in-cheek comment and a mirror of the current imagery of violence in today’s public discourse. The motif of Islamist terrorism, especially, reads like an eerie and startling premonition of what would actually be possible in the future, when placed against the backdrop of the escalated pace of Islamist terrorism in France after the Charlie Hébdo attack and the Bataclan massacre of 2015. In one chapter that portrays the scene of an explosion of twelve female suicide bombers in burkas in front of the Notre Dame cathedral, Weissner offers a wry comment on the pornographic media spectacle following acts of terrorism: the first responders after the blast are a camera team in a helicopter hovering above the carnage.

Besides the social critique and commentary, the violence of Death in Paris is also indebted to the elements of the hardboiled detective novel, of which Weissner was an obvious fan. The book opens with a quote by Raymond Chandler as a motto: “There must be idealism, but there must also be contempt.” (Chandler in: Weissner 2012, title page) Chandler’s quote refers to an anti-elitist attitude toward his audience and is also applicable to Death in Paris, only with a twist. Weissner’s book is surely not for the faint of heart.

If taken literally, the novel is clearly not idealistic. The contempt it demonstrates toward humanity is one not of moral superiority but rather of misanthropic disgust. Yet there is a lot of pleasure in the violence dealt out in the novel on a metaphorical level, and Chandler also offers some clues why.

In a brief essay on the history and poetics of the hardboiled genre entitled “The Simple Art of Murder,” Chandler argues that violence was a valid motor for the plot:

[…] the demand was for constant action; if you stopped to think you were lost. When in doubt have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand. This could get to be pretty silly, but somehow it didn’t seem to matter. A writer who is afraid to overreach himself is as useless as a general who is afraid to be wrong (Chandler 1964, ix).

Violence in Chandler’s understanding is also a metaphor for literary creation, as the power by which the author can shape characters, direct the plot, but also let his own creatures live or die. Weissner coming to himself again as a writer must have enjoyed and realized this kind of freedom. Why else would he have played with such chapter headings as “I now declare Place d’Estienne d’Orves a free fire zone” (49)?

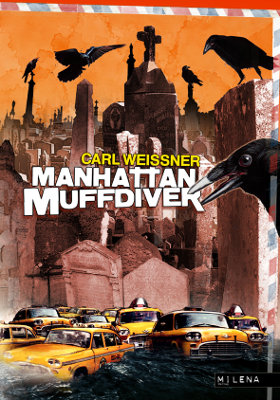

This leads me to my final remarks, namely to the question about the importance of the locale for this text. The book is, after all, entitled Death in Paris, and as I have shown, there is plenty of death, but how much Paris is there? There is a passage in Manhattan Muffdiver, where the narrator refutes the claim that New York as an iconic city of the twentieth century and as a symbol of all things modern has been told and retold to exhaustion, that there is nothing new that can be said about it. (Weissner 2010, 56) As proof for this claim, he not only documents the overabundance of his current experiences in the metropolis, the druglike quality of the city, (Weissner 2010, 73) but also in a backward movement, he unearths, in the vein of an urban archaeologist, obscure facts and histories connected to places in the city. He holds them before him and the reader like a cutout fragment and ponders on its compatibility with the composite of his narration. Sometimes the pieces fit, and sometimes they do not. The same is true for Death in Paris, where the temporal gaze of the narrator oscillates between an extrapolated apocalyptic future, and ghosts of places and people caught in a multitude of layers of the past. Paris has also not been narrated to exhaustion, Gerald Lake informs us, as he contemplates, for example, the obelisk on Place de la Concorde, or the Ile de Puteaux:

Two hundred years from now, gothic pirate scum, mutated beyond the pale, will do a cannibal shindig on the exact spot where the guillotine decapitated the king… And the tattered ghosts of rescue divers from Petit Clamart will search, one final futile time, for the drowned bodies of Isadora Duncan’s kids downstream from the Ile de Puteaux. … The two children rolled into the Seine on the backseat of her Bugatti when the chauffeur went for a pack of cigarettes and forgot to pull the handbrake. Son cosas de lavida. (81)

Works Cited

Chandler, Raymond. 1964. The Simple Art of Murder. 3rd Printing. New York: Pocket Books Inc.

Schäfer, Frank. 2010. “Carl Weissner: ‘Ich Hab’’ Nicht Mehr Ewig Zeit”.’” Die Zeit, sec. Literatur. http://www.zeit.de/kultur/literatur/201003/carlweissnerinterview.

Weissner, Carl. 2010. Manhattan Muffdiver. Milena Verlag.

———. 2012. Death in Paris. Tokio: Doll No Mori.

Judging from notebook entries, it seems apres DiP and Trashman, Carl envisioned writing the tale of a young post war kraut – and he gave yarns of his youth in the Signe Maehler film, didn’t he. Just testing?

In a 2010 interview (in Konkret magazine; a facsimile can be found at http://carl-weissner-biblio.com/doc/deutsche_konkret.html) Carl mentions, ‘Meine Hauptfigur (der Vierzehnjährige in dem ungeschriebenen Wälzer) hat mit mir kaum etwas zu tun, wird aber mit einem gewissen Haß auf die Republik ausgestattet. Wer Deutschland seit dem 14. Geburtstag nur von außen wahrnimmt und in englischen oder französischen Zeitungen bloß den deutschen Klatsch und die Entgleisungen geliefert bekommt, muß irgendwann zu dem Ergebnis kommen, das sind granatenmäßige Dumpfbacken. Oder Kannibalen. Oder beides.’ –– I’ll try give a rough trl: ‘My protagonist (the 14 yr old in that unwrit tome) doesn’t have much to do with myself, yet he’s equipped with a certain hatred of the Republic. Anybody who since his 14th birthday perceives Germany only from the outside, picking up all these screw-ups from english or french newspapers, will conclude those krauts are dumb as hell. Or cannibals. Or both.’

For those ‘yarns of his youth” and, even better, a real sense of Carl’s personality, have a look at the Signe Maehler film here:

http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/2013/01/carl-weissner-cherished-by-friends-and-colleagues.html

(Just scroll to the end of the blogpost and click on the video. The film starts at roughly a minute and a half in and runs for 20 minutes.)