![European Beat Network [Sept. 20-22, 2017] Paris Interzone, The Transcultural Beat Generation](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/beat-conference-ebsn-paris-1-240.jpg) I wish I could be there when the European Beat Studies Network meets in Paris on Wednesday. Douglas Field (University of Manchester) will give a presentation about Harold Norse’s “Cosmographs.” I remember seeing them on the wall of Norse’s room at the Beat Hotel more than 50 years ago. As I’ve written in My Adventures in Fugitive Literature and in a new edition of The Z Collection, to be published by Blue Wind Press, Norse was very proud of them. They had been exhibited with a commentary by William Burroughs, which was not only “effusive,” as Field says, but also essential. Norse recalls in his Memoirs of a Bastard Angel that he had begun painting at the suggestion of a friend and patron, Julia Laurin, and that Burroughs had “taken him up” even before he was installed in the dingy lodgings at 9, rue Git-le-Coeur, where Burroughs was already living:

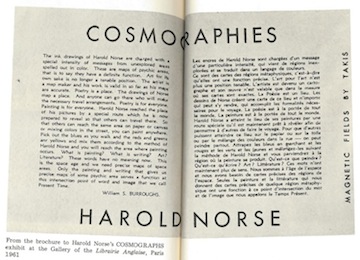

I wish I could be there when the European Beat Studies Network meets in Paris on Wednesday. Douglas Field (University of Manchester) will give a presentation about Harold Norse’s “Cosmographs.” I remember seeing them on the wall of Norse’s room at the Beat Hotel more than 50 years ago. As I’ve written in My Adventures in Fugitive Literature and in a new edition of The Z Collection, to be published by Blue Wind Press, Norse was very proud of them. They had been exhibited with a commentary by William Burroughs, which was not only “effusive,” as Field says, but also essential. Norse recalls in his Memoirs of a Bastard Angel that he had begun painting at the suggestion of a friend and patron, Julia Laurin, and that Burroughs had “taken him up” even before he was installed in the dingy lodgings at 9, rue Git-le-Coeur, where Burroughs was already living:

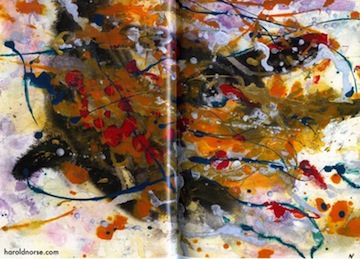

I threw colored Pelican inks at random on Bristol paper and washed them off in the bidet with startling results: a series of map-like drawings of outer and inner space in the most vivid colors and minutely precise details, as if they had been meticulously drawn by a master hand. Yet my hand never touched them. I allowed everything to happen, letting the laws of chance take over, acting as a medium through whom these colors, shapes, and designs could flow, dictated by whatever forces reside in the unconscious. with the feeling that I was charting new territory in the visual arts I worked compulsively, calling the results “Cosmographs”—cosmic writings. I was no draftsman, but I was an artist.

One of Harold Norse’s ‘Cosmographs.’

Click to enlarge.

The ink drawings of Harold Norse are charged with a special intensity of messages from unexplored areas spelled out in color. These are maps of psychic areas, that is to say they have a definite function. Art for its own sake is no longer a tenable position. The artist is a map maker and his work is valid in so far as his maps are accurate. Poetry is a place. The drawings of Norse map a place. And anyone can go there who will make the necessary travel arrangements. Poetry is for everyone. Painting is for everyone.

Harold Norse reached the place of his pictures by a special route which he is now prepared to reveal so that others can travel there. So that others can reach the same area on paper or canvas or mixing colors in the street, you can paint anywhere. Pick out the blues as you walk and the reds and greens and yellows and mix tem according to the method of Harold Norse and you will reach the area where painting occurs. What is painting? What is writing? Art? Literature? These words have no meaning now. This is the space age and we need precise maps of space areas. Only the painting and writing that gives us precise maps of some psychic areas serves a function at this intersection point of word and image that we call Present Time.Introduction by William S. Burroughs.

Click to enlarge.

Burroughs was not the only one impressed by the “cosmographs.” In his 1989 memoir, in a chapter titled “The Bidet School of Art,” Norse quotes a laudatory review of the show by John Ashbery. It appeared in the Paris edition of the New York Herald-Tribune on March 22, 1961. “Painting with color inks on wet paper,” Ashbery wrote, “Norse produces fantastic webs, maps or labyrinths, and strange combinations of iridescent color.”

What I find more interesting is that, according to the memoir, Ashbery told him that his drawings

had inspired him to begin painting, which he had always wanted to do. When I said that like my cut-up fiction and poetry it was based on aleatory techniques, he exclaimed, “I’ve been doing it for years! I pore through the dictionary, books, and magazines, pick out words at random, and string them together.” He scoffed at the “newness” of the technique when I told him what we were doing at the hotel. “Tzara did it forty years ago,” he sniffed. “I did it in my teens and twenties,” I said, “using the dictionary, but destroyed it.” “It certainly works in your painting,” he said.

Harold Norse in 1988

Photo by Allen Ginsberg.

The show was an artistic, social, and financial success. Le tout Paris — the most exclusive, snobbish, aristocratic clique in Paris — attended. Among those impressed was Henri Michaux. “Tres brien, vraiment, mais il faut aller plus loin, plus loin!” he said cryptically. James Jones and Mme. Laurin were at the vernissage, as well as distinguished painters, some of whom made appreciative noises, while others remained aloof. Julia bought a drawing and Jones bought two. When Allen Ginsberg arrived at the end of March, Peter Orlovsky, with a long face, said, “I must tell you, we don’t like it.” They didn’t like cut-ups either. Though at first [Gregory] Corso participated in the cut-up technique, he and Allen felt threatened by the random use of language. Their identity as poets was at stake. (It’s interesting that Ashbery, who later achieved the pinnacle of poetic success, did so precisely with the random means they feared and rejected.) “You can’t please everybody,” muttered Burroughs with lofty indifference.

Norse continues:

Stoned on hashish, like most of the others, I lost control when a Dutch painter, Guy Harloff, mad with envy that I, a poet, had a show when for years he had tried without success to have one, threatened me. He was six foot seven and I five foot four, but when he insulted me … I pinned him to the wall with my arm on his throat. His eyes bugged out and he would have suffocated had Norman Rubington, an American painter and writer, not intervened.

Years later in Athens I heard that a new group of painters in Paris, calling themselves Cosmographers, had founded a school based on my method. I immediately christened it “Bidet Art.” After all, as an innovator I’d have been ungrateful not to mention the part played in the creation of my drawings by this toilet appliance, which possessed the symbolic significance that the urinal had for Marcel Duchamp; furthermore, the bidet had produced cosmic effects — thereby affirming in art the function of objects despised because of stupid moral prejudices. I proved that if Alice could enter the fourth dimension through the looking glass, I could do so through the bidet.

As the Brits say, brilliant.