Dear Gerard,

I stayed overnight in London with John Lahr, an old writer friend, and we both went together to the funeral. First, everyone convened at H’s old house (an artisan’s cottage in St. Bernard’s Road, Jericho). It was strange being there with so many people, and the house cleaned up as well! We overflowed into the garden which had also had a severe lopping of shrubbery, and it was there that I suddenly broke into tears.

H’s coffin of woven willow lay on a table to one side of the sitting room. The top was covered in paper hearts, and we were invited to write a message on an old-fashioned type of luggage label which we could then attach to the side of the basket-coffin. After about an hour we were invited to line up outside behind the coffin, which was then hoisted onto the shoulders of fit young men, and we proceeded to process around the weaving streets of Jericho, led by a large base drum which maintained a mournful beat. The traffic was held up in a few places and people came out from cafes and restaurants to watch us pass; some, their jaws maintaining a silent prayerful-looking mastication. Women ran back and forth kissing and hugging each other. There was a beautiful feminine energy flowing through the procession. It all reminded me of the way in which the local kami or god of a village or small town in Japan is ritually carried around the streets of the neighbourhood on a bier, in order to maintain the bond between itself and the parish.

After quite a long journey, the Italianate campanile of St. Barnabas Church came into view, and its single tolling bell conjoined with the drumbeat as though beating for the great heart which had now ceased.

Entering the cavernous space of the main body of the church was like entering the body of a whale, and we were greeted by the disembodied voice of Heathcote reading from Whale Nation which descended among us from the lofty painted vault of its vast roof space. Prayers and hymns were offered, including a hymn which H had written especially for the church only just recently. Gray Gowrie gave a very moving reminiscence of his very long friendship with H (they were at Eton together), and a wonderful appraisal of his work. I didn’t recognise him at first, he looked so gaunt, and moved crablike on two sticks. And either by permission of my modesty, or a licence to my vanity, I have to tell, there was a reference to a piece of writing of mine called “The Realm of Hungry Ghost,” which was referred to by one of the eulogists who lived nearby and visited H regularly, and possessed the same gift of oratory as any of the speakers in H’s brilliant book, The Speakers.

However, even at the event and hour of its confirmation, I still couldn’t grasp the fact of H’s having gone. When I last visited him, I asked him not to leave the planet before me. He obviously didn’t hear me. The acceptance will come slow as the silences and gaps in the inbox of my laptop reveal just that; the absence. No more, “Here’s something…”, “Take a look at…”, “See what you think of this…”, “I’ve been…”

The interesting thing for me was the realisation that while my friendship with H was always intimate and personal, that others too had similar relationships. And that slowly as speakers spoke about his work, H began to separate somewhat from my personal, historical space, and appear in a vast cultural landscape and as a native of that place.

I had written a piece for The Guardian which they said they couldn’t publish in its present form as it was “too personal” and that others “would want to write likewise”. I was angry about it, and explained that it was about a beloved friend, and that I didn’t want it published if they were going to cut it. However, someone phoned me to say that they had published it, in a meaningless and truncated form of two paras!

I raise a glass with you to our old friend, my friend,

Postscript: My staff of thousands tells me that even digital-savvy viewers may not click links they can mouse over but don’t easily see — the link embedded in the photo above, for instance, which would take them to a list of Straight Up blogposts by or about Heathcote that have appeared in recent years. So here’s the link made visible.

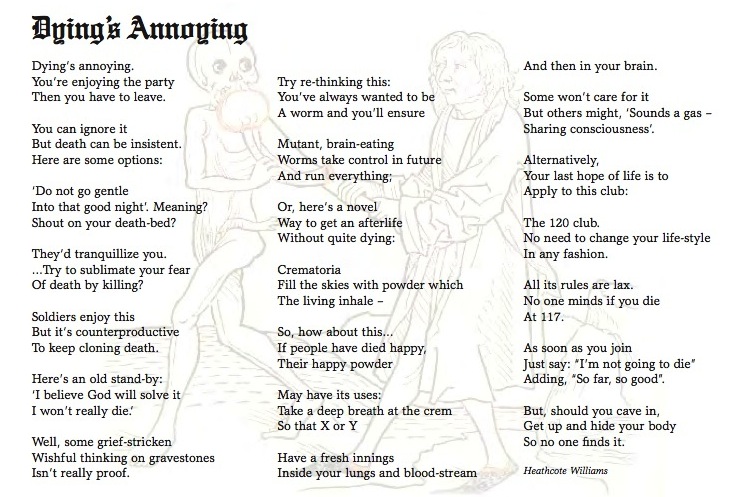

Heathcote was an unstoppable force. Characteristically, in an interview with The Guardian in May of 2016, when his play “The Local Stigmatic” was getting a London revival, Heathcote remarked: “Am I pleased it’s getting redone? I’m thinking more about what I want to do next.” He was always thinking about that. And doing it. Even in death he is unstoppable. His writings, his activism, and his personal example will continue to inspire others. Have a look:

He invented an idiosyncratic ‘documentary/investigative poetry’ style … bringing a diverse range of environmental and political matters to public attention.

If Art, if poetry is not revolutionary, then it is not Art, then it is not poetry!

Boris Johnson: the man with no moral compass who became UK foreign minister.

PPS: July 2 — From The Guardian obituary by Luke Harding:

At heart, Williams was a revolutionary. The historian Peter Whitfield placed his work in a “great tradition of visionary dissent” stretching from William Blake and John Ruskin to DH Lawrence and David Jones. His poems – blasting the arms trade, consumerism and the tabloids – were “wonderfully innocent” and at the same time “wonderfully streetwise”.

And another obituary by Michael Coveney, also in The Guardian, describes him as “a unique and brilliant writer — poet, dramatist, visionary and pamphleteer.”

He restored and renovated a sense of intellectual anarchy in our public discourse in the great traditions of Jonathan Swift, William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley, all of whom were among his heroes. […] The quality of anger is usually strained, but Williams’s muse was fuelled by a witty and beautiful anger that he channelled in three great poems at the end of the 1980s: Whale Nation, a wonderful hymn to the largest of all the mammals and a plea for their protection, Sacred Elephant, and Autogeddon, a JG Ballard-style ballad about the plague of the motor car; all three were filmed by the BBC, the third performed by Jeremy Irons.

Williams himself made notable recordings — in his day, he was a charismatic troubadour –of Buddhist scripture, Dante and the Bible, and a collection of shorter poems, Zanzibar Cats (2011), which skewered political absurdity, planetary destruction and social justice mishaps with delightful glee and great verbal dexterity.

Speaking of recordings, I had the privilege of recording Heathcote’s final vinyl LP-cum-CD, “American Porn,” at his home in Oxford three years ago. He read “Mr. President,” “The United States of Porn,” “Forbidden Fruit, or The Cybernetic Apple Core,” and “Snuff Films at the White House” — which in their uncompromising nakedness are CT scans of history. He was dead serious, no glee included but not strained either.

July 4 — The obit in The Washington Post, by Harrison Smith, catches Heathcote in the moment:

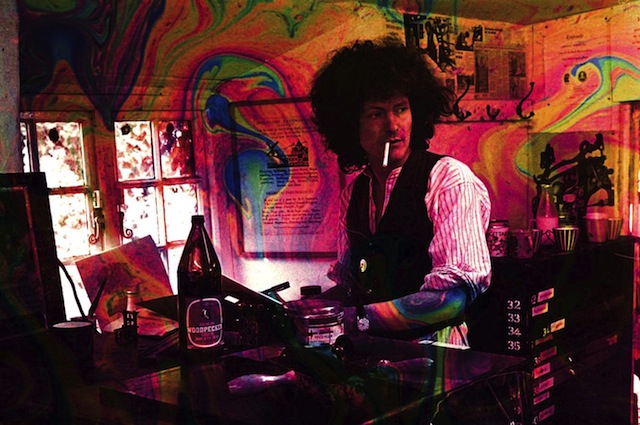

Smith goes on to give many other magnificent details:Mr. Williams, a reedy Oxford University dropout who for many years sported black combat boots and a mass of curly red hair, emerged from Britain’s 1960s counterculture movement as a sort of artistic Prospero, a gifted but mischievous writer whose creative talents recalled those of Shakespeare’s sorcerer in “The Tempest.”

He wrote a dozen plays, many of them critical of society’s increasing obsession with celebrity; published several scholarly book-length poems on endangered animals; and co-founded an anarchist publishing house, Open Head Press, that skewered Britain’s royal family in pornographic postcards and scurrilous pamphlets.

Mr. Williams also appeared in more than a dozen film and television roles, including as Prospero in Derek Jarman’s 1979 adaptation of “The Tempest,” and helped start the “sex paper” Suck, an underground Amsterdam publication at the fore of Europe’s sexual liberation movement.

He performed as a fire-breather (at one point accidentally setting himself on fire), practiced conjuring tricks, contributed to a television show about Charles Dickens’s love of magic, and struck up a relationship with Jean Shrimpton, the ’60s supermodel who helped popularize the miniskirt.

Despite being championed by figures ranging from the playwright and Nobel laureate Harold Pinter to Hollywood actor Al Pacino, Mr. Williams’s work often received little public attention — in large part because of its difficult subject matter and experimental style.

His groundbreaking play “AC/DC,” which premiered at London’s Royal Court Theatre in 1970 and opened in New York the following year, concluded with a trepanation — the piercing of a character’s skull.

The play, New York Times critic Charles Marowitz wrote in a review, placed Mr. Williams alongside Pinter, John Osborne and John Arden as one of the leading playwrights of the era. “It is,” he wrote, “the only play yet written to capture the tremulously combustible nature of the 21st century, which, because our mortal lives always trail chronology, is the century in which we are actually living.”

Performed amid closed-circuit television sets, with photographs of famous people plastered on the theater walls, the show was perhaps the first major theatrical work to criticize the glorification of celebrities in the television age, said New Yorker theater critic John Lahr.

“It’s arcane and not going to be popular, but as a little thought kit it puts all the others to shame,” he said in a phone interview. “His understanding of the imperialism of celebrity — no one comes close in the English theater. And that is one of the most toxic obsessions of our time.”

Mr. Williams turned from playwriting to overt political activism by the late 1970s, joining with graphic designer Richard Adams to design and distribute pamphlets, postcards and other documents in the tradition of Britain’s 18th- and 19th-century “radical squibs.”

Their headquarters, in London’s Notting Hill neighborhood, eventually served as a base of operations for a short-lived secessionist state that Mr. Williams and other leaders called the Free and Independent Republic of Frestonia, as well as an organization called the Ruff Tuff Cream Puff Estate Agency, which helped squatters find abandoned buildings in London to use as temporary housing. [. . .]

Mr. Williams’s commercial breakthrough was a departure from the skull-piercing of his early years. In “Whale Nation” (1988), “Falling for a Dolphin” (1989) and “Sacred Elephant” (1989), he mixed poetry with scholarship to spotlight endangered species that he sometimes studied firsthand, including on a six-month trip to the western coast of Ireland.

Still, politics was not a subject he could avoid for long. Last year he published a pamphlet, “The Blond Beast of Brexit: A Study in Depravity,” that collected unsavory quotes from Boris Johnson, who was then the mayor of London.

“There’s a German word for people like Johnson: Backpfeifengesicht,” Mr. Williams told the London Independent, explaining what drew him to the subject. “It means ‘a face that needs to be punched.’ ”

And now you MUST read the 1974 New York Times review by Charles Marowitz that Smith references, headlined: “The Importance of Understanding Heathcote Williams.” It may be the best piece of all in its description of who he was:

I’ve been told that not long ago Heathcote Williams was fined for ripping up a pavement near Green Park and planting some shrubbery there. It is exactly the kind of act one would expect from him — an extravagant demonstration of good sense calculated to show how the world is being run by zombies. He is co‐founder “with a million others, of a new nation under God — the Albion Free State.” To the British, who view such shenanigans as the routine gestures of the avant‐garde, Williams is, at best, an eccentric; more likely, a mental.

But I find Heathcote Williams one of the few people I have ever met whom I would call pure in heart. It is precisely this purity of heart that causes him to investigate the corrosion in the hearts of others.

Wow.

July 5 — It’s gratifying to see Heathcote’s “purity of heart” acknowledged. But I notice — couldn’t help noticing — that none of the obituaries pointed out Heathcote’s rich late works published by Cold Turkey Press. Not even a passing mention. Nothing about his Harold Pinter: A Portrait, or Burroughs in London, or his beautiful reminiscence My Dad and My Uncle, or the takedown of His Bobness Of Dylan and His Deaths, all published by Cold Turkey. Although they were produced in handmade editions limited to only 36 copies, so that few people are likely to know of them and even fewer to have read them, they still represent a late flowering that has been ignored. And if the rarity of those late literary works is justification for ignoring them, how come there was only the slightest nod in one obit to Shelley at Oxford, which was published more broadly by Huxley Scientific Press and is now in a second edition?

I really can’t fault the obit writers for overlooking the details of these works, since they are writing to deadline and can hardly be expected to comment on works they haven’t read. I’m fairly certain that even if they caught sight of this blogpost, which not only lists all those works and others, and which offers digital versions of almost all of them, including his polemical investigations, they would not have had time to read through so much literary material or all the postings at IT: International Times, The Newspaper of Resistance, where Heathcote was the editor of the paper’s online revival. Nevertheless, overlooking that late flowering is a huge error and should be corrected somehow, perhaps by a collection of his late writings and/or his best writings from all the periods of his work. And not least, somebody knowledgeable about the British scene should pitch a mainstream publisher for a biography, while interest is high.

July 6 — And now The New York Times has weighed in with its obit by William Grimes. It appeared yesterday online but not yet in the print edition. Since Grimes is the paper’s lead obit writer for cultural and literary figures, it’s likely to appear in the paper very soon, probably in tomorrow’s edition.Grimes inevitably recounts many of the details that appeared in the previous obits, sometimes verbatim, but he also gives many others. For instance, he explains that Frestonia, the anarchist country which Heathcote cofounded, got its name from “a nearby street, Freston Road” in the neighborhood where it was located. I’d always wondered, why that name? Now I know.

The NYT obit also offers a welcome link to Heathcote’s classic anti-royalist poem “I Will Not Pay Taxes”: “Although rumpled and scruffy, Mr. Williams had a plummy accent and a mellifluous speaking voice that served him well . . .” I’m surprised the link wasn’t scrubbed because it takes you to a video launched with the words “FUCK TAXES” on screen in all caps. Like so:

And here’s another link the NYT obit offers: “Mr. Williams was a restless sort. Marianne Faithfull turned his savage lyrics about sexual betrayal, “Why D’Ya Do It?,” into one of the most memorable cuts on her 1979 album, “Broken English.” To avoid the commercial, here’s where that link takes you:

If Heathcote were still here, I believe he’d be grinning.

July 7 — The obit in the print edition of the NY Times appeared today. It received major placement on the back of the main news section with a headline running across all five columns, calling him a “Poet Who Wielded a Palette of Outrage.”

It’s time I wrapped up this blogpost with a personal reminiscence. I corresponded with Heathcote for five years, beginning in 2012. We exchanged thousands of emails over that period, and I met him for the first and only time in September of 2013. My description of that meeting appeared as the liner notes on the vinyl LP of “American Porn”:Had I believed that Heathcote Williams was difficult to meet, that his reputation for turning fans away from his door was true, as a bookstore proprietor in his neighborhood assured me it was, I would have been a very nervous visitor. But he’d been so open and friendly in our email exchanges, messaging at one point, “When you and your wife come to Oxford, you must both come by for a slap-up Oxford tea,” that it never occurred to me to be nervous. He had even sent a photo of his front door to make it easy to find him.

And in fact on the Saturday we visited, Heathcote welcomed us with a broad smile, leading us immediately into his kitchen, where there on the table was a spread he had prepared himself: two dozen neatly stacked salmon and buttered cucumber sandwiches trimmed of their crusts, dozens of jumbo crevettes he had shopped for, many sweet cakes, two kinds of juice, and a pot of tea already brewing on the stove. It certainly discredited one fan’s claim that “when people ask themselves ’round for tea, he says things like, ‘I’m sorry but I’ve only one cup.’”

Of course our visit had been arranged through Heathcote’s close friend of many years, the painter and publisher Gerard Bellaart, which guaranteed a warm reception. Also, our visit was not just a matter of fandom. It had a purpose. I was there to record the three poems on his vinyl album. We got on so well, however, chatting about everything from Heathcote’s early plays of the ’60s and his time as an editor at Transatlantic to his relationship with William Burroughs and his return to playwriting — he’s written a new play, “Killing Kit,” about Christopher Marlowe — that we needed another day to record him.

But to dwell on the warmth of Heathcote’s welcome and the pleasure of his company is to belie the fierce dissidence of what he is about as a poet. “Mr. President,” “The United States of Porn,” and “Forbidden Fruit, or The Cybernetic Apple Core” are poems that I think of as CAT scans of history. They are history investigated and exposed. In their uncompromising nakedness, they tell the moral truth beneath journalism’s proverbial first draft. And the truth is not that welcoming.

Take “The United States of Porn.” The poem runs to 208 lines, nearly all based on fact: “Amerigo Vespucci, of Florence, a peddler of pornography, / Set his seal on America …” The name you knew about, but not about the porn. To put a finer point on it, “Thus America and its dream were named after a porn writer / Who worked for the Medici, the mafia of the Middle Ages.” Nor may we forget, “As befits a country named after the murderous Medici’s gofer, / America spends more money on weapons each year / Than the whole world spends on food and drink.” Although the poem hardly represents a threat to the military-industrial complex, it is subversive literature hidden in plain sight with the power of old-time samizdat.

“All his work,” Harold Pinter, a champion of Heathcote’s writing, has said, “is deeply political. I think it’s informed not only by violent contempt for the way people are manipulated, for the status quo, the complacency of the status quo, but also — certainly more and more evident in his later work — by compassion for the weak.” What Pinter once described as Heathcote’s “nausea at one’s own romanticism and vulnerability and weakness in allowing oneself to be sucked in by film stars, and heroes, and politicians” — Pinter was speaking of Heathcote’s 1965 play “The Local Stigmatic” — is as accurate today as it ever was.

Furthermore, Heathcote at age 72 is so prolific — writing by night and sleeping by day [if at all] in a cramped room on the top floor of his home, a lair stuffed with books and papers — that the typewriter keys of his laptop have gone blank, all the letters rubbed out by constant use. But it’s the words he produces on those keys that are indelible, like the richness of his voice on his recording. “Heathcote is one of a few of genius who did not sell out,” says Gerard, “and who peak in relative old age. That’s quite something nowadays.”

July 21 — Here is a description of the funeral by Roddy McDevitt (with a photo by Max Crow Reeves) and another description by Stephen E. Hunt. And here is a magnificent elegy by Boff Whalley.

![Heathcote Williams [Photo: JH, 2013]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/heathcote-williams-photo-copy.png)

![Heathcote Williams at the Frankfurt Bookfair, 1980 [Photo: Richard Adams]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/heathcote-1980-365.jpg)

![Heathcote Williams at the Open Head office, 1980. [Photo: Richard Adams]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Heathcote-Williams-photo-richard-adams-220.jpg)

![Obit in NY Times print editon [July 7, 2017]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/hw-nyt-obit-print-edition-july-7-2017.jpg)

![Heathcote's coffin of woven willow being carried through the streets of his Jericho neighborhood in Oxford on July 14, 2017. [Photo: Max Crow Reeves, courtesy IT: International Times, The Newspaper of Resistance]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/H-funeral-procession-Photo-by-Max-Crow-Reeves-750.jpg)

I am shocked. So many memories.

‘Severe Joy’, the collection of Heathcote’s sixties and seventies work Savoy never managed to produced, will now haunt us. RIP, friend and inspiration.

Great title. Can that project be resurrected? Perhaps Thin Man Press in London would be interested? It recently published the print edition of “American Porn.”

http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/2017/01/american-porn-for-inauguration-day.html

Since reading THE SPEAKERS in the 1960’s I have never not taken Heathcote seriously and with deep affection for his having caught and fixed what is utterly central, fugitive and rarely found or sought after. It is a highly inappropriate time for his leaving – who will now deliver the news?

I am not surprised at the amount of grief and loss being expressed in social media and from contacts, but was somewhat ambushed by my own sharp sadness. We were only in touch a couple of times in the past year, after more than a decade of no contact at all. However, have hugely rich memories of 60s at Transatlantic Review, 70s and 80s cross publishing and a few adventures. Further along from this, I need to write something about that, otherwise will be lost. Maybe Gerard should do a book for H similar to one for Beiles.

Regards Severe Joy – Mike B and I ran some of that when we were doing Wordworks, then he and Dave used extracts again in the Savoy anthologies. Calder was going to bring out the book (at H’s request I got a friend to produce an illustration for it) ; Calder kept promoting it as forthcoming – on dust jackets of other books up till ’79 when he listed it as published. Same time he promoted the “original account” of The Speakers was in preparation. Neither one ever happened. I am curious how much of H’s work will come to light now, although possibly a lot that will not surface for years – he wasn’t good at keeping copies.

Yes, the obits still popping up – some using too much Wikipedia and samples of other obits but no alarming errors, just small ones. Coveney in the Guardian was good, but his Ken Campbell book was pretty nice too. WashyPost references H contributing to TV show on Dickens and magic, but might actually be meaning What The Dickens! the telly play he wrote about Dickens and the foundlings he invited to his home at Christmas. Open Head was in Ladbroke Grove, not within Frestonia, which had its own HQ (was also its National Theatre, first performance there was The Immortalist).