So much art is called “avant garde” these days that my tireless staff of thousands wonders whether it’s just a label. Some think that the entire culture, no matter how far out, has gone mainstream and that there’s nothing legitimately avant garde anywhere — not since the good old days of Dada, surrealism, cubism, futurism, serialism, modernism, postmodernism (insert your favorite “ism” here).

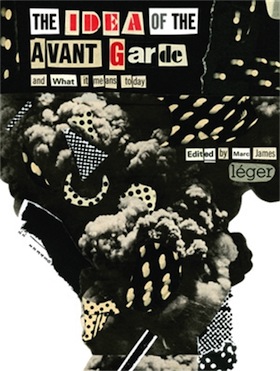

Well, Marc James Léger has news for the staff. He has put together an anthology, The Idea of the Avant Garde and What it Means Today, filled with an exhaustive combination of scholarly essays, interviews with artists, and examples of their work that explain the current situation. But hold on tight. The book is like a juggler balanced on a human pyramid. To enjoy the dizzying sensation of it, you have to be prepared. In his introduction (entitled “This Is Not an Introduction”), Léger lays out his thinking in terms that let you know what to expect. His thoughts are not for the faint of heart or mind. When “global capitalism and post-welfare state governments” are in charge, he writes, “various forms of cultural practice, critical thinking [and] autonomous production” typically encounter “some kind of rightist pressure” (lack of funding, for example). “In this context, cultural production depends on and facilitates the extension of neoliberal control.”Therefore “disaster capitalism” makes it “all the more vital to address the interest, the pleasure and radical potential of the avant garde.” So “rather than accept the postmodern attitude that considers all talk of avant-gardism as so much canonical boilerplate, or as business marketing,” Léger says he conceived the anthology as a way to “facilitate a cross-generational transmission of ideas that have little to do with creative innovation, nor with any artist’s or art movement’s apotheosis, but that instead thinks critically about what we do as artists and theorists.”

Critical thinking for Léger, a widely published artist, writer, and art theoretician based in Montreal, boils down to a concept derived from an historical analysis by Renato Poggioli. Poggioli traced the idea of the avant garde to mid-19th-century French and Russian notions that, as Léger explains, “art has a mission of social reform and that it can agitate for change through the production of revolutionary propaganda.” Poggioli, who was writing during the Cold War era of the 1960s, “attempted to bring the anti-traditional of the avant garde up to date by considering how it manages to live and work in the present, how it can reconcile itself to the culture of the times by collaborating with parts of the public.” * See footnote.

These days, though, collaborating with the public can be a bit of a problem. The culture of the times as described by Adrian Piper in her essay, “Political Art and the Paradigm of Innovation,” is a lousy rotten hodgepodge of messed up, overfed, needy, rapacious, inevitably unhappy consumers of unoriginal ideas, copycat products, and all-around crap. Piper puts it more analytically, of course. She is a conceptual artist with a PhD in philosophy from Harvard, a half-dozen traveling retrospective exhibitions behind her, and a two-volume collection, Out of Order, Out of Sight: Selected Writings in Meta-Art and Art Criticism, published by MIT Press. She writes:The culture of unrestrained free-market capitalism feeds on the shared and foundational experience of incompleteness, inferiority — of generalized insufficiency, or want. The experience of generalized want is created by media fabulations of a fantasy world of perpetual happiness that sharply contrasts with our complex and often painful social reality, plus the promise that this fantasy world can be realized through the acquisition of those material goods that serve as props within it. For those who have the wealth to acquire such props, this promise is broken on a daily basis, and the hollow dissatisfaction at the core of perpetual acquisition is a constant reminder that something is missing. Unfortunately, this dissatisfaction only rarely leads to the interrogation of the basic premise of the fantasy itself — i.e. that the acquisition of material props can realize it in the first place. Usually the conclusion is, rather, that more props are needed to do the trick.

That’s not all.

How then do avant-garde artists actually deal with this? They create or try to create niches for themselves, sometimes with the introspective focus of a meditative encounter. Marina Abramovic’s exhibition “The Artist is Present” is one example; a deep-listening concert at a retreat led by the composer Pauline Oliveros would be another. But just as often, and probably more so, there are artists who seek their niche with showy demonstrations of transgressive intent. One such is the German artist Jonathan Meese, the subject of “Why Contemporary Artists Are Not Fascist Enough,” an essay by BAVO (the research collective of Gideon Boie and Matthias Pauwels) that points to an interesting paradox. They write:This is the function of the globalized advertainment industry. Based in the American myth of acquisition and consumption, it offers tantalizing desire-satisfaction events as palliatives to the agonies of conscience caused by America’s historical crimes against humanity and their present consequences. And it is nourished internationally by comparable agonies in other countries: the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, of the British Empire, the Second World War in Germany and Japan,the Soviet regime in Russia, the Cultural Revolution in China, to name only a few. The globalized advertainment industry exploits our shared need to escape from the morally unbearable present of those consequences, by producing ‘new and improved’ goods and services that deaden their pain and divert our attention. And it expends enormous resources convincing us to want them. That is, the advertainment industry creates interminable and insatiable desire for the new that narcotizes the ugly realities and moral self-dislike inherited from our past atrocities; it promises an end to that self-dislike in repetitive infusions of desire-satisfaction. The enduring themes or originality and innovation that characterize the discourse of modern art — indeed, contemporary culture more generally — is merely one example of that dynamic.

Early in the twenty-first century, the idea of popular culture seems to have established itself once and for all as the dominant paradigm within the arts. Among policymakers as well as the people, the consensus is that art needs to have the broad support of society. The contemporary artist is expected to be fascinated with the societal context in which she lives, to involve as many parties as possible in the artistic production process. … Participation, democratization and social integration are the terms and criteria that are now firmly rooted in art practice. They dominate both policy documents on art as well as the discourse of artists and curators.

![Meese gives the Nazi salute in his installation "Hot Earl Green Sausage (First Flush)' at the Bortolami Gallery in New York, 2011. [Photo: Jan Bauer]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Meese-Diktatur-der-Kunst-365.jpg)

Jonathan Meese with his installation ‘Hot Earl Green Sausage (First Flush)’ at the Bortolami Gallery,

New York City, 2011.

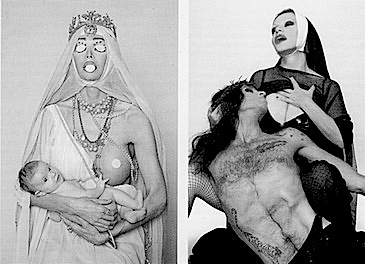

There’s no question about genuinely transgressive intent when it comes to Bruce LaBruce, whose essay “Don’t Get Your Rosaries in a Bunch” describes an exhibition of his photographs in Madrid and the reactions to it particularly from an outraged conservative group called Make Yourself Heard, which described the show as, “Gay-looking angels encouraging lechery, lascivious nuns posing in underwear, reveling in crucifixes or cradling a tattooed Christ between their breasts … this is the new content of the provocative exhibition ‘Obscenity.'”

Left: ‘Madonna and Child’ [2011]. Right: ‘Pieta’ [[2011]

Courtesy of La Fresh Gallery. © Bruce LaBruce

Who would have thought that nunsploitation could cause such a ruckus in this day and age? All you have to do is Google “sexy nuns” on the Internet and you will be confronted with literally thousands of images of the brides of Christ in kinky lingerie and fetish gear, fishnet stockings, and garters. You will find drag queens as nuns, masochistic nuns, dominatrix nuns, whatever your evil heart desires. It’s a well-established genre. I mean, it’s not as if I invented the Catherine Wheel! For those a little more adventurous, a quick perusal of PornTube or X Tube will show you porn stars dressed up as priests and nuns doing the dirty deed. That’s the function of porn: a play space where people are allowed to vicariously act out their darkest, most secret and politically incorrect fantasies. It’s probably what allows civilization to move forward without repressing or denying its desires to the point of having them reemerge in some monstrous and much more dangerous form. Porn is good.

My staff is sure that John Waters, who does not appear in The Idea of the Avant Garde, would have chuckled over the brouhaha. The theme of LaBruce’s essay goes well beyond a defense of pornography, however, to a wider concern about a “conservative trend in art,” which maintains, like Léger’s intro, that it is “reinforced by neoliberal economic strategies of disaster capitalism.” LaBruce singles out Damien Hirst as the most prominent representative of that trend, citing his “aggressively meaningless, overpriced, and infinitely unoriginal polka dot paintings” as both the embodiment and beneficiary of a “bland, smug period.”

Similarly transgressive, Rabih Mroué writes in “Spread Your Legs” that after the premiere of Who’s Afraid of Representation? in Beirut, he and his associates were summoned to the censorship department of the General Security office because they had failed to get bureaucratic approval for the performance. They were promised that their criminal misdemeanor would be ignored if they agreed “to remove and replace all words and expressions which “offend public taste” or “offend the morals of our society” or those that “would give rise to sectarian strife.” They also had to “remove and replace all mention of the country’s president and its army, and refrain from naming anything, whether politicians, sexual organs or otherwise.” Mroué lists the required changes. Here are a few:

Replace My tits with My breasts.Remove They could fondle them and play with them.

Replace the word Whore with Prostitute.

Replace My cunt was on display with I was on display.

Remove I spread my legs wide.

Remove the word Mouth from Pee

Remove

Replace Shit with Excretion.

Replace And started to smear shit all over my body

with I started to smear my body.

Remove Amal Movement and replace with The movement.

Remove the word Lebanese from the sentence When the

Remove I bought a woman’s corpse and had sex with it.

Remove Stuck it here, in my cunt and replace with I stuck it in me.

Mroué adds:

On the following morning, we presented the play with the new, amputated text. However, the English translation of the old text, performed during the uncensored premiere, remained. The censor missed this little detail; he didn’t mention the English text. We presented the full English text without removing or replacing anything, as we had in the Arabic. We considered this a victory. [But] knowing that English in Arabic-speaking countries is of little concern … our victory was like a silly joke that only makes the person who tells it laugh.

These examples hardly scratch the surface of a 285-page collection of largely double-columned, densely argued texts spiced throughout with illustrations from all fields of artistic enterprise, including music and poetry, architecture and environmental science, film and video, social action and technology, history and philosophy, and aesthetic theory (lots of that). With more than 50 contributors from around the world, it addresses many different notions of the avant garde, not just the one I’ve emphasized. But if any theme unites The Idea of the Avant Garde and What It Means Today, it is that by all definitions the avant garde opposes conformity and authority, and despises orthodoxy in any form, whether political or cultural. I can hear someone saying, “We knew that already!” True enough. But it’s the brilliantly curated elaborations of the argument — and so many of them — that make this book a landmark.

* Responding to this notice, Léger writes: “I actually question the conclusions drawn by Poggioli, which as far as I see it, leads him to pluralism, which is what we’ve known from the 1970s to the postmodern 80s and cultural studies 90s. My theory is that the shift to macropolitical activist art around the 2000s signals a recognition that the pronouncements of the “end of ideology,” which as Richard Barbrook notes in his book on ‘Imaginary Futures’ has been rehearsed by the Cold War Left since at least the 1950s, are not only premature but simply false.

![From a poster on New York City's Lower East Side advertising the 2010 MoMA exhibition 'The Artist is Present.' [Photo: Moe Angelos]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/abramovic-MoMA-cropped-365.jpg)

Good to see the avant-garde is alive and welling.

Thanks for this review. I actually question the conclusions drawn by Poggioli, which as far as I see it, leads him to pluralism, which is what we’ve known from the 1970s to the postmodern 80s and cultural studies 90s. My theory is that the shift to macropolitical activist art around the 2000s signals a recognition that the pronouncements of the “end of ideology,” which as Richard Barbrook notes in his book on ‘Imaginary Futures’ has been rehearsed by the Cold War Left since at least the 1950s, are not only premature but simply false. John Waters btw was one of the many people invited to contribute to IAG, but he was travelling cross-country at the time, working on what became the book ‘Carsick: John Waters Hitchhikes Across America’. I also invited Spike Lee, among some of the high profile artists. A second volume of IAG, with another 50 contributors, is already written but waiting on a publishing deal. cheers, MJL