In his critique of “I Am Not Your Negro,” the movie bringing renewed attention to James Baldwin, Hilton Als comments on a key moment:

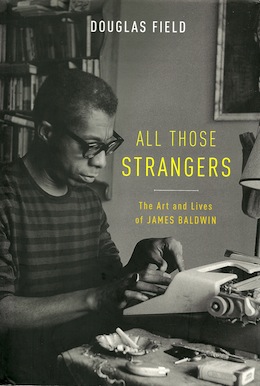

Let me suggest that Douglas Field has an answer to that question in his recently published biographical study, All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin. Field writes:It’s the summer of 1979, and Baldwin is working on a book that he does not want to write but knows he must write. Titled “Remember This House,” it will tell the story of America through the lives of Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X, all of whom were Baldwin’s friends, and whom he wrote about in his underrated 1972 book, “No Name in the Street.” (One wonders why he chose to revisit the material — or why it wouldn’t leave him alone.)

One of Baldwin’s enduring traits seems to have been his willingness to revel in the role of maverick and disturber of the peace. … Amid the cacophony of charges that he was too old, out of touch, or an ailing novelist, Baldwin repeatedly refused to be pinned down or to be held to account. … Baldwin’s insistence on self-definition and suspicion of what is now termed identity politics serve as an important rejoinder to the theory’s attempts at fixity. Baldwin’s refusal to view identity or history as fixed serves as a pertinent reminder that his own work was continuously evolving, highlighting the need to read it in the context(s) of the four decades in which his writing emerged. …

One of the most striking features of Baldwin’s work is his ability to demonstrate integrity and commitment while at the same time insisting on the right to oscillate, prevaricate, and think through philosophical questions with the reader. In No Name in the Street, for example, he ponders the term “Afro-American,” which he picks apart as “a wedding … of two confusions, an arbitrary linking of two undefined and currently undefinable proper nouns.” Even as Baldwin struggles to find a language for the peculiar condition he describes — “These questions — they are too vague for questions, this excitement, this discomfort” — he brings the reader with him on his urgent moral, philosophical, and intellectual enquiries, which are not about rhetoric, but about the dangerous and compelling condition of twentieth-century life in America, the continent of Africa, and beyond.

It can’t help being said that with the 21st-century emergence of the United States of Trumpistan the domestic discomfort, let alone the worldwide danger, is more true than ever.

Feb. 9 — Crossposted at IT: International Times.

It’s a minor thing, but this phrase bothers me a bit, “his willingness to revel in the role of maverick and disturber of the peace.” In a literal sense, revel means to “enjoy oneself in a lively and noisy way, especially with drinking and dancing.” Even if given a wider interpretation, it makes it sound like he enjoyed his protest, or that it was an assumed persona, when in reality his motivation was deep alienation. It was a passion that was the very basis of his life. I think his moral consciousness was a great burden and not something in which he reveled. I think it was this profound commitment that set him apart from many writers. Just a thought. Who knows?

Incisive all around.

This simple edit would address the issue Osborne raises: “One of Baldwin’s enduring traits seems to have been his willingness to be a maverick and disturber of the peace.”