William Wyler’s anti-macho Western “The Big Country,” which is remarkable for its imposing visual beauty and sonorous musical score, makes it to the (relatively) big screen at the New York Historical Society (as in bigger than your flatscreen TV but smaller than the screens it was made for back in 1958).

The movie is also remarkable for a lot more than its lush production — not least the way it debunked the Western cliché of score-settling violence. All of this is likely to be discussed by Wyler’s daughter, the documentary film producer Catherine Wyler, who will introduce the screening on Friday in conversation with HBO’s Susan Lacy (best known for creating the “American Masters” series on PBS).

The movie is also remarkable for a lot more than its lush production — not least the way it debunked the Western cliché of score-settling violence. All of this is likely to be discussed by Wyler’s daughter, the documentary film producer Catherine Wyler, who will introduce the screening on Friday in conversation with HBO’s Susan Lacy (best known for creating the “American Masters” series on PBS).

Some background: It was 1956. Wyler had long since earned the right to independence. But even as his career and reputation thrived, all his attempts to gain total control of his pictures — in deals with Liberty, Paramount, and now Allied Artists — had fallen short. So Wyler decided to join forces in a venture with Gregory Peck, who had become a close friend. Peck announced that they would make a comedy, “Thieves Like Us,” about an art heist of El Greco and Titian masterworks from the Prado in Madrid.

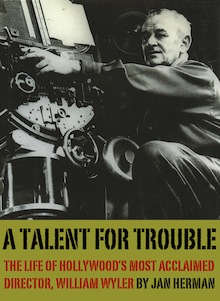

“This thing didn’t happen out of the blue,” Peck told me when I interviewed him for my Wyler biography, A Talent for Trouble. “Willy and I had grown very close. We spent holidays together at Sun Valley with our families. We were always dining out together. It would be the Wylers at the Pecks or the Pecks at the Wylers. [Our wives] Veronique and Talli really liked each other. We were a foursome. We’d been together in Rome [making ‘Roman Holiday’], and we’d been very happy. The idea of doing that again in Madrid seemed quite appealing.”But the script for “Thieves Like Us” didn’t work out, and the project was dropped.

Then James Webb, a screenwriter who’d co-written many Westerns, brought Peck a story by Donald Hamilton, “Ambush at Blanco Canyon,” which was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post and later expanded into a novel, The Big Country.

“I took the story to Willy,” Peck said, “and asked him what he thought of making a big-scale Western. I told him I thought there were half a dozen very good parts, so we could do some great casting. I also thought the theme would appeal to him. It was kind of an anti-macho Western.”

The setup seemed perfect. Peck had a development deal with United Artists, which would finance and distribute the picture, but he and Wyler would be the bosses. The pair divided their producing responsibilities and formed separate companies. Wyler’s was World Wide Productions; Peck’s was Anthony Productions, named for his infant son. Wyler would be in charge of all things artistic. Peck would have casting and script approval, and he would handle the ranching aspects of the picture: hire the wranglers, rent the livestock, choose the horses, in effect serve as foreman.

But that was the beginning of their difficulties, and it complicated the making of “The Big Country.” I cover the entire story — the troubles between Wyler and Peck that ensued on and off the set, the making of the movie, and its mixed reception — in the biography.

Postscript: British film professor Neil Sinyard’s appreciation of “The Big Country” in his brilliant book on Wyler’s movies, A Wonderful Heart, is the best I’ve read.

!['The Big Country' [released October, 1958]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/the-big-country-640.jpg)

One of the greatest movie themes of all time. The film itself isn’t all that great – too long and predictable. But the score made the movie.