But Butterwoth’s tale really begins in Manchester, where he and his writing partner David Britton founded Savoy Books and where they fought a decades-long battle against censorship by authorities who were — yes — powerful, corrupt, and liars to the marrow of their bones.

“For over twenty years, a virtual state of war existed between the Manchester police and us, colouring everything we did,” Butterworth writes. “Trouble began with the rise to power of James Anderton, ‘God’s Cop,’ who took over the Chief Constable of greater Manchester Police Force slot in 1976, just after we had started publishing.”

The Chief arrived with a mission. He claimed to have been visited by God, who told him personally to “clean up the city. (In his campaign, Margaret Thatcher supported him.) The appeal of our shops to youth and the outré meant that we quickly became his prime targets Between 1976 and 1999, the Greater Manchester Police raided us about a hundred times.

Butterworth and Britton had founded Savoy above a locksmith shop and branched out with a small chain of bookshops that helped finance their publishing operation. The cops were looking to confiscate hardcore porn. But their raids on Savoy’s shops and other retailers, including news agents and a major department store, were ridiculous (not to mention destructive). “The laugh was that there was nothing really to ‘clean up,'” Butterworth recalls. “Hardcore porn was not being sold at any of those shops. Nor did we sell it. It would get you jailed. We just wanted to publish books.”

But that didn’t matter to the authorities.

Police officers — men and women — helped themselves to our stock, making off with adult magazines, underground comics, horror magazines, occult literature, drug manuals, gay contact magazines, biker mags, books on body piercing, tattoo magazines. Once I can remember seeing a policeman climb into the shop window at Bookchain to seize a display copy of a Conan book. With its Frank Frazetta cover art, depicting a muscular bronzed barbarian wearing a Viking helmet, they believed it to be gay porn. Sometimes, the police just stripped the shops’ entire contents.

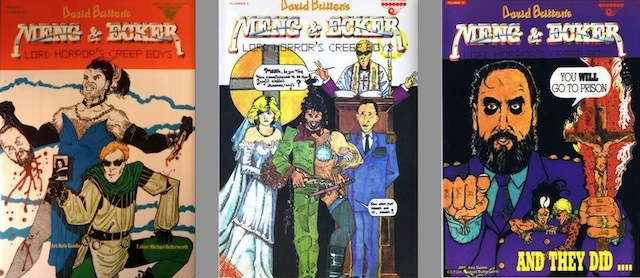

Unwilling to back down, Butterworth and Britton and the artists they published raised the ante. “Our Meng & Ecker comics lampooned the police overtly, while the Lord Horror miniseries made more subtle attacks on them. We undoubtedly stoked the conflict,” Butterworth writes, “to keep going as serious publishers.” They felt they had to draw the attention of the national media, because under the rule of God’s Cop “a culture of collusion existed between the city’s judiciary and the police that would otherwise have carried on unnoticed.”

The increased hostilities and “the pressure of the raids” resulted in the forced liquidation of Savoy Books, in 1982, and a jail term for Britton, who was “sentenced to twenty-eight days in Strangeway Prison.”

Butterworth writes that they retreated but were still undeterred. They opened a new bookshop and a rehearsal space for Manchester rock bands hidden away from public view. This allowed them to keep going by “packaging music and comedy books for other publishers,” often assembled by the two of them under pseudonyms. New Order felt a kinship with Butterworth, and he kept a diary about his experience of their recording sessions.This was the first of two jail terms. In 1993 David served another four months for writing Lord Horror, published in 1989. The book was the first novel to be banned in Britain since Hubert Selby Jr’s Last Exit to Brooklyn in 1967. His imprisonment became a cause célèbre, and resulted in our one ‘win’ over the police. In the full glare of the national media the ban was overturned in the Crown Court. [Yet] the police raided us again, the very next day.

“It was our brand of defiant “art for art’s sake” publishing in the face of police harassment that impressed New Order and it was thanks to Savoy’s evident concern for artists,” he notes, “that they allowed me to write about them.”

The most important and subversive novels that Savoy has published, along with Lord Horror, are undoubtedly its two sequels — Motherfuckers: The Auschwitz of Oz and Baptised in the Blood of Millions.

Keith Seward explains in Horror Panegyric, an exegesis (with excerpts) of the novels — which Butterworth cites in his memoir as “the best account” of the predicament he and Britton had faced — that the novels succeed by applying to literature “the Boschian method.” They satirize “via hyperbole and excess.” (See Not the Yellow Brick Road.)Motherfuckers’ principals are Meng and Ecker, twins who had been subject to “scientific” experiments by Josef Mengele. After the war they find themselves in northern England, waiting for Lord Horror the way others wait for Godot. Ecker is rational but violent, Meng is a mutant whose huge cock and tits are nothing compared to the mutations of his mind. Not Holocaust survivors in any sense you’ve ever seen before, Meng and Ecker have adopted the ways of their captors — the bloodlusts and hates. However, there is nothing paramilitary about them. They’re not neo-Nazis or skinheads. They’re more like the ultraviolent droogs of A Clockwork Orange, though it is quite possible that the droogs would not feel any affinity in return. Meng and Ecker are even further out in some post-war delirium. Auschwitz, meet Oz.

Here’s a recent interview of Butterworth looking back at it all, beginning with avant-garde literary magazines like New Worlds and Ambit, and his relationship with J.G.Ballard, in connection with a museum installation of his work:

Postscript: After this blogpost went up, Butterworth messaged that Savoy’s decision to produce music owed an enormous debt to the example of Open Head, a subversive print-based publisher in London at the time. In the book, he described what happened.

As well as my experience of being in a studio at Brit Row, other influences played their part in David and I taking the joint decision to become music producers. One of the biggest was a series of demo tapes and vinyl discs that had been arriving on our desk from the London-based Open Head press since around 1977. Run by the anarchist poet-playwright Heathcote Williams and Oz/IT designer Richard Adams, Open Head was a print-based publisher — yet they were producing music. Such departures by our peers into a new medium had an incendiary effect on us. The arrival on our desks of their record ‘Sid Did It’ (1979) — a Sex Pistols pastiche released under the moniker of Nazis Against Fascism, with vocals by Ben Brierley and spoken contributions by Marianne Faithfull — and a sexually explicit ‘Why D’Ya Do It?’ penned by Williams for Faithfull’s 1979 album, Broken English, acted like our ‘Lesser Free Trade Hall moment’ when the Sex Pistols performed in the block next door to Bookchain, inspiring Bernard and Hooky and a generation of young Manchester musicians.

If Heathcote and Richard could do this, then so could we. Williams’ audaciously clever fictions were both magical and dangerous — some of Open Head’s productions were regarded as seditious — and we published them as often as we could. The publications I gave to Ian Curtis to read nearly all contained contributions from Williams, such pieces as ‘The Abdication of QE II’, an obscene, black-humoured, anti-monarchical fantasy depicting the abdication of the Queen; ‘Natty Hallelujah’ about a Rastafarian blissed out on joints and cosmic orgasms; ‘Security Leak From the Future: Or Things Liberation’, concerning the revolutionary uses of Kirlian photography; plus the song lyrics and poems penned for Faithfull.

Open Head’s treasonous postcard of Prince Charles fondling the breasts of a smiling naked Princess Diana sold in its thousands throughout the country. Of course we also sold it in our bookshops. A copy ended up in the Haçienda’s first DJ box, pasted there as a visual memento, where it remained until the box was moved up onto the club’s balcony.

Other Open Head postcards showed Maggie Thatcher stealing from a housewife’s shopping bag, or a smiling Maggie giving a V-sign (not for ‘Victory’). Heathcote and Richard were eventually warned by plainclothes agents of the Crown and had to desist. But their press continued producing publications of remarkable subversive energy and diversity. David and I weren’t anti-monarchy per se, but the insubordinate cleverness and design of these productions — books, magazines, posters, postcards and recordings — was an impressive lesson in how to project an artistic mixed-media ideology. We later used Open Head as a model for the multi-media satirical Lord Horror ‘Savoy Wars’ and ‘Moral Ambiguity’ campaigns launched in the mid-eighties, commencing with the Lord Horror cover of ‘Blue Monday’.

At the same time as Open Head’s music productions, we were being acquainted with the fierce irreverent energy of early club tracks like D.A.F.’s ‘Der Mussolini’ (1981). Later, in 1984, came Funkmeister’s ‘War Dance’, which sampled wartime radio broadcaster Lord Haw- Haw’s voice over a dance beat (from hearing this, David made Haw-Haw the model for Lord Horror). Such numbers had a mad surreality to them. They were mixed into the mainly punk and rock’n’roll playlists at our bookshops.

Crossposted at IT: International Times, The Newspaper of Resistance.

Update: Still a Clockworks of Suppressed Emotion (Jon Pareles on New Order’s March 10 concert at Radio City Music Hall in New York).

!['The Blue Monday Diaries' by Michael Butterworth [Plexus Publishing, 2016]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Blue-Monday-diaries.jpg)

!['Lord Horror' [Savoy Books, 1989]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lord-horror-147.jpg)

!['Motherfuckers: The Auschwitz of Oz' [Savoy Books, 1996]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/motherfuckers147.jpg)

!['Baptised in the Blood of Millions' [Savoy Books, 2001]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/baptised-147.jpg)