I have always loved the way A Walk on the Wild Side begins. Show me a more perceptive opening of an American novel with its historical tracing of an Appalachian clan (let alone the lyrical brilliance of its prose) and I’ll buy you dinner.

The novel introduces Fitz Linkhorn on the first page — a “man so contrary,” someone says, “he’d float upstream”:

The novel introduces Fitz Linkhorn on the first page — a “man so contrary,” someone says, “he’d float upstream”:

Six-foot-one of slack-muscled shambler, he came of a shambling race. That gander-necked clan from which Calhoun and Jackson sprang. Jesse James’ and Jeff Davis’ people. Lincoln’s people. Forest solitaries spare and swart, left landless as ever in sandland and Hooverville now the time of the forests had passed.

Whites called them “white trash” and Negroes “po’ buckra.” Since the first rock had risen above the waters there had been not a single prince in Fitzbrian’s branch of the Linkhorn clan.

Unremembered kings had talked them out of their crops in that colder country. That country’s crops were sea-sands now. Sea-caves rolled the old kings’ bones.

Yet each king, before he had gotten the hook, had been careful to pass the responsibility for conning all Linkhorns into trustworthy hands. Keep the troublemakers down was the cry.

Nelson Algren’s novel comes to mind this morning because of an op-ed column by Steve Inskeep in the New York Times, Donald Trump’s Secret? Channeling Andrew Jackson, which explains that Trump’s fans “are heavily concentrated in and near the Appalachian states — from Mississippi and Alabama all the way to western Pennsylvania and New York.” He adds that “the northwestern corner of South Carolina [where the Republican presidential primary will be held on Feb. 20] is one of the most pro-Trump parts of the country.” Inskeep elaborates:

Greater Apalachia has remained culturally distinct for centuries. Migrants from the northern British Isles — Scots, Scots-Irish and others — pushed into these mountains in large numbers from the 1700 onward and did much to create the nation as we know it. Their descendants weather generations of hardship and calamity: washed out hillside farms, coal-mining disasters and extreme poverty. … To live or work in Appalachia is to feel the tug of its past.

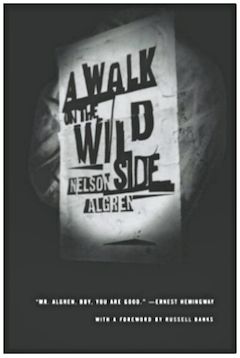

The column, which goes on to describe Jackson’s Scots-Irish heritage and his real-estate fortune built on “a personal empire of cotton plantations” using black slave labor, makes me wonder whether Inskeep ever thought of A Walk on the Wild Side. Probably not. The routinely journalistic prose of his analysis weighs against that. Besides, Algren’s novel was published more than a half century ago, in 1956, and was trashed by the critical establishment. But Inskeep might as well have been channeling it. The novel’s opening continues like this:

Duke and baron, lord and laird, city merchant, church and state, landowners both small and great, had formed a united front for the good work. When a Linkhorn had finally taken bush parole, fleeing his Scottish bondage for the brave new world, word went on ahead: Watch for a wild boy of no particular clan, ready for anything, always armed. Prefers fighting to toil, drink to fighting, chasing women to booze or battle: may attempt all three concurrently.

The first free Linkhorn stepped onto the Old Dominion shore and was clamped fast into the bondage of cropping on shares. Sometimes it didn’t seem quite fair.

Through old Virginia’s tobacco-scented summers the Linkhorns had done little cropping and less sharing. So long as there lay a continent of game to be had for the taking, they cropped no man’s shares for long.

Fierce craving boys, they craved neither slaves nor land. If a man could out-fiddle the man who owned a thousand acres, he was the better man though he owned no more than a cabin and a jug. Burns was their poet.

Slaveless yeomen — yet they had seen how the great landowner, the moment he got a few black hands in, put up his feet on his fine white porch and let the world go hang. So the Linkhorns braced their own narrow backs against their own clapboard shacks, pulled up the jug and let it hang too. Burns was still their poet.

Forever trying to keep from working with their hands, the plantations had pushed them deep into the Southern Ozarks. Where they had hidden out so long, saying A Plague On Both Your Houses, that hiding out had become a way of life with them. “It’s Linkhorn’s war. We don’t reckon him kin of our’n.” they reckoned.

Later they came to town often enough to see that the cotton mills were the plantations all over again: the prescriptive rights of master over men had been transferred whole from plantation to mill. Between one oak-winter and one whippoorwill spring, the Linkhorns pushed on to the Cookson Hills.

And then the novel moves further on in time and place, taking us “three score years after Appomattox” to the Rio Grande Valley, where “Linkhorn showed up in the orange-scented noon,” and where “had there been an International Convention of White Trash that week, Fitz would have been chairman.” Afterward it moves on yet again, with Fitz’s son Dove Linkhorn, to the redlight district of New Orleans. Go read Walk. You’ll not only be enlightened, you’ll be entertained.

![Nelson Algren in Sag Harbor, N.Y. [ca. 1980]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Nelson-Algren-in-Sag-Harbor240.jpg)