I notice that the NYT Sunday Book Review’s not-so-special “Special Issue” on graphic books (Oct. 18) makes no mention of ‘Red Rosa’ by Kate Evans, forthcoming from Verso (Nov. 3). My tireless staff of thousands decided to right that wrong.

!['RED ROSA: A Graphic Biography of Rosa Luxemburg' by Kate Evans [Verso, 2015]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/red-rosa-cover-e1445091051718.jpg) Kate Evans, aka Cartoon Kate, is no ordinary biographer. Her in-depth account of the socialist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919), Red Rosa, edited by Paul Buhle, traces both the life and the work in the distinctive style of a consummate comic-book artist. But Evans is also no ordinary comic-book biographer, a rare category in any case. Red Rosa has 23 pages of doubled-columned scholarly notes at the back of the book explaining the basis of virtually every dialogue balloon and every panel of narrative.

Kate Evans, aka Cartoon Kate, is no ordinary biographer. Her in-depth account of the socialist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919), Red Rosa, edited by Paul Buhle, traces both the life and the work in the distinctive style of a consummate comic-book artist. But Evans is also no ordinary comic-book biographer, a rare category in any case. Red Rosa has 23 pages of doubled-columned scholarly notes at the back of the book explaining the basis of virtually every dialogue balloon and every panel of narrative.

When you read Red Rosa, flipping between the notes and the narrative, it feels like a hologram of ideas because you see not only the actual texts used for the dialogue, but also the context. Evans cites primary sources, largely books and letters that Luxemburg wrote, as well as the works of Karl Marx, whose socio-economic theories Luxemburg spent a lifetime analyzing and elaborating. Evans not only cites primary sources, but also the lack of them. She is scrupulous about that. For example, early in the book she depicts 10-year-old Rosa and her family in the aftermath of a devastating pogrom in Warsaw. A racist mob has raged down their street, “women raped and men murdered for being Jewish.” A back-page note explains: “Although it passed her house, neither she nor her family ever mention it, so it is possible that they were not in Warsaw at the time.” The note also delineates the anti-Semitic laws passed the following year and gives a quick yet detailed summary of their pervasiveness.

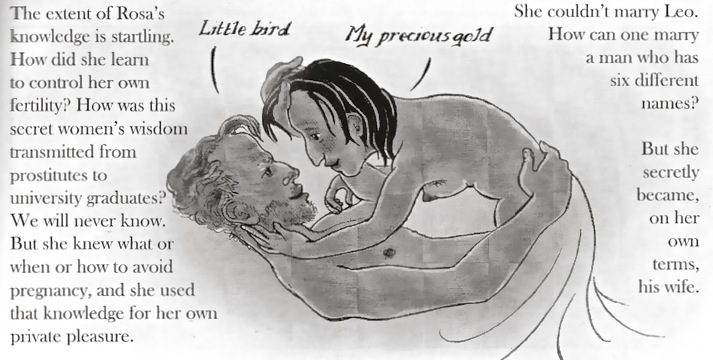

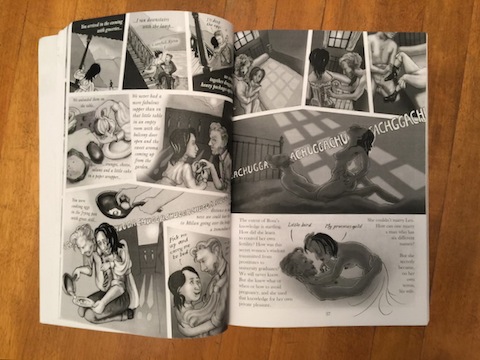

For all the contextual history, Red Rosa is never dry. Evans examines the most personal details of Luxemburg’s life. Two charioscuro pages depict the beginning of her pleasurable but difficult and complicated love affair with the self-absorbed, emotionally distant Leo Jogiches, one of the most important people in her life. In an extensive treatment of the intimate details of their lusty romance, culminating in panel drawings that portray their mutual sexual satisfaction, Evans writes in a back-page note: “The textual authority for Luxemburg achieving orgasm is implied in a letter to Jogiches describing a moment of conflict between them. … If Luxemburg wasn’t deriving physical pleasure from sexual relations, there would be no impetus for her to initiate sex, and therefore no possibility of Jogiches misinterpreting her need for affection as a desire for sex.”

For all the contextual history, Red Rosa is never dry. Evans examines the most personal details of Luxemburg’s life. Two charioscuro pages depict the beginning of her pleasurable but difficult and complicated love affair with the self-absorbed, emotionally distant Leo Jogiches, one of the most important people in her life. In an extensive treatment of the intimate details of their lusty romance, culminating in panel drawings that portray their mutual sexual satisfaction, Evans writes in a back-page note: “The textual authority for Luxemburg achieving orgasm is implied in a letter to Jogiches describing a moment of conflict between them. … If Luxemburg wasn’t deriving physical pleasure from sexual relations, there would be no impetus for her to initiate sex, and therefore no possibility of Jogiches misinterpreting her need for affection as a desire for sex.”

How do you beat that for interpretive biographical commentary? In a comic book, no less. The note goes on:

The question of exactly how Rosa Luxemburg managed to avoid becoming pregnant in her sexual relations with men [she had more than a few lovers] will never be conclusively answered. It is worth noting that although she never discusses contraception or fertility awareness, there is a reference in her correspondence to the menstrual cycle: I have a feeling similar to that which a forty-year-old woman certainly has, when the physical symptoms of sex life stop showing up. Luxemburg, Letters, p. 42

Ever scrupulous, Evans writes that the tale she tells is “a fictional representation of factual events.” But that is only because she has made several changes “in order to compress a life as rich as Rosa’s into 179 pages.” Although “minor events have been omitted” and “some peripheral characters have been conflated,” along with some deviations from the historical record (“in a few places the chronology of events has been reversed for dramatic effect”), Evans is remarkably faithful to the facts of Luxemburg’s intellectual and romantic life, and her ultimately tragic death. In addition to parsing and updating Marx’s economic theories, analyzed with a clarity that makes this biography a brilliant teaching device, Evans stresses her unflinching personal courage and the feminist aspect of her revolutionary beliefs (even if Luxemburg herself preferred not to promote feminism).

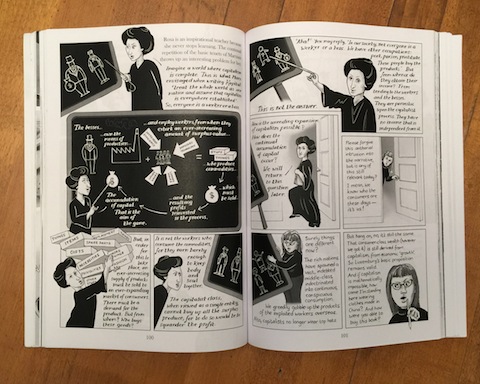

The overriding theme of Red Rosa reflects Luxemburg’s and the author’s own radical devotion to Marxism and its proof of the injustices of capitalism. In a series of panels, using direct quotes from Luxemburg’s masterwork, The Accumulation of Capital, originally published in 1913, she shows how this “inspirational teacher” laid out the tenets of Marxist theory. Evans eases the lesson with a light touch, however: She puts in a personal appearance in the last three panels of the spread. Peeking in the door of the classroom, she says, “Please forgive this authorial intrusion into the narrative, but is any of this still relevant today?” And taking over the blackboard, she adds, “Surely things are different now?” Of course they are. The rich nations of today “have spawned a vast, indebted middle-class indoctrinated into continuous, conspicuous consumption. We greedily gobble up the products of the exploited workers overseas. Also capitalists no longer wear top hats.”

The overriding theme of Red Rosa reflects Luxemburg’s and the author’s own radical devotion to Marxism and its proof of the injustices of capitalism. In a series of panels, using direct quotes from Luxemburg’s masterwork, The Accumulation of Capital, originally published in 1913, she shows how this “inspirational teacher” laid out the tenets of Marxist theory. Evans eases the lesson with a light touch, however: She puts in a personal appearance in the last three panels of the spread. Peeking in the door of the classroom, she says, “Please forgive this authorial intrusion into the narrative, but is any of this still relevant today?” And taking over the blackboard, she adds, “Surely things are different now?” Of course they are. The rich nations of today “have spawned a vast, indebted middle-class indoctrinated into continuous, conspicuous consumption. We greedily gobble up the products of the exploited workers overseas. Also capitalists no longer wear top hats.”

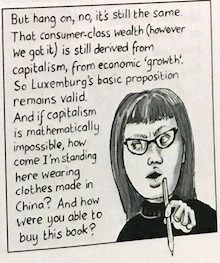

But hang on, no, it’s still the same. That consumer-class wealth (however we got it) is still derived from capitalism, from economic ‘growth’. So Luxemburg’s basic proposition remains valid. And if capitalism is mathematically impossible, how come I’m standing here wearing clothes made in China? And how were you able to buy this book?

If the bedrock of this biography is its combination of Marxist theory and historical narrative — including but not limited to Luxemburg’s participation in the international socialist movement, German politics, and the Russian Revolution of 1905 — the motherlode is its touching portrayal of a woman who sacrificed her life for her beliefs. Despite betrayal by allies, vilification by opponents, and disillusionment with Lenin and the Bolsheviks — and notwithstanding constant police harrassment and years of imprisonment for her revolutionary activities and her opposition to the first World War — Luxemburg remained indomitable up to the moment of her assassination at the age of 47, in 1919, by paramilitary thugs.

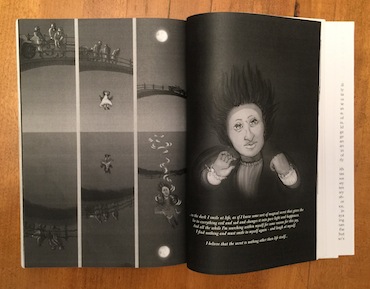

Red Rosa ends with a series of moody two-page spreads that recapitulate her life. This one, quoting a letter she wrote from prison, expresses her unconquerable spirit …

…in the dark I smile at life, as if I knew some sort of magical secret that gives the lie to everything evil and sad and changes it into pure light and happiness. And all the while I’m searching within myself for some reason for this joy, I find nothing and must smile to myself again — and laugh at myself. I believe that the secret is nothing other than life itself …

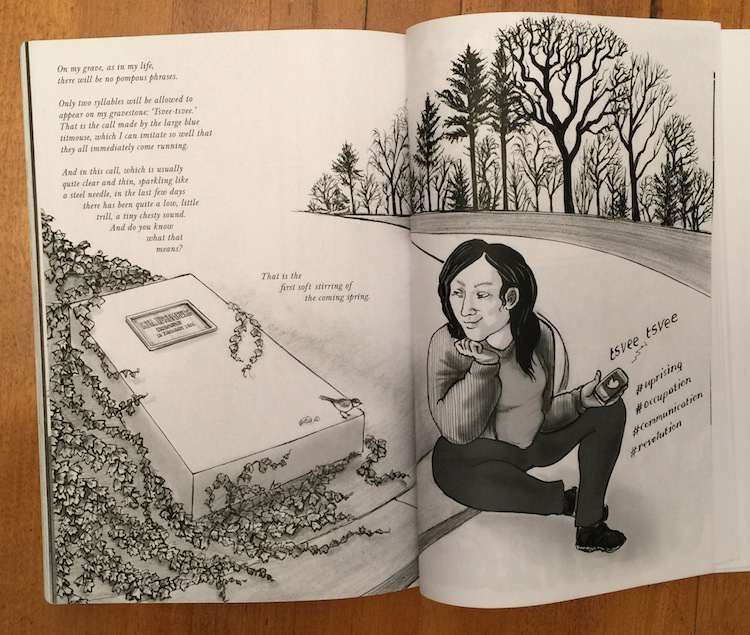

On my grave, as in my life, there will be no pompous phrases.

Only two syllables will be allowed to appear on my gravestone: ‘Tsvee-tsvee.’ That is the call made by the large blue titmouse, which I can imitate so well that they all immediately come running.

And in this call, which is usually quite clear and thin, sparkling like a steel needle, in the last few days there has been quite a low, little trill, a tiny chesty sound. And do you know what that means?

That is the first stirring of the coming spring.

Crossposted at IT: International Times.

Postscript: Nov. 23 …