‘It is Deborah Davis’s style to pan to a faraway object, complete its history, then cinematically bring it into the focus of the story. John Huston becomes cinema verité. Her style permits one to learn everything related to the trip. Even things Andy Warhol’s diarist didn’t know.’

‘It is Deborah Davis’s style to pan to a faraway object, complete its history, then cinematically bring it into the focus of the story. John Huston becomes cinema verité. Her style permits one to learn everything related to the trip. Even things Andy Warhol’s diarist didn’t know.’

By Charles Plymell

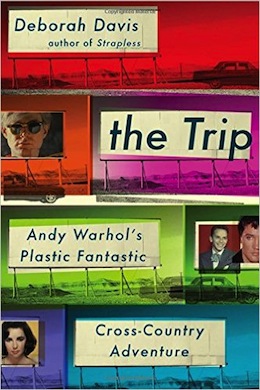

“The Trip” it was … with the successful advertising artist who had a movement stirring in his head, a hunk kid skipping out on his poetry semester of school, never been out of the Bronx, who met so many famous people, he just added photography and silkscreening to his resumé and never looked in the rear view. The driver, Wynn Chamberlain, was a fairly normal-looking human commandeered by Warhol for his Ford Falcon. Then there was Taylor Mead, the “movie star” poet I first met ca. ’61 in Venice, California, when he was a local fixture with his stolen grocery cart (to haul his belongings) and his faithful transistor radio tied to it. Descriptions of the characters evolve fully in the book with Ms. Davis’s incredibly concise lines, trimly coiffed, loaded with subtle humor that discretely has no problem with the hard-edged vernacular of the time only found in truck stops and underground publications.

“Tall Wynn, goofy Taylor, ghostly Andy and hipster Gerard” sat in a booth at one of the largest “Streamline Moderne” roadside diners on Rt. 66 somewhere in cowboy hat & boots truck driver country in Oklahoma when all eyes turned toward them.

They climbed back into the Falcon and headed out to the bold American Pop art signs and Burma shave rhymes that WERE the art and literature of my first trip in 1939 in the back of our International wheat truck (the family car) to my aunt’s orange grove on the rim of the L.A. basin when it WAS indeed paradise! It was a time and place where everything was a wild ride up and up and up. “Inside out and outside in.” The neon signs of gossamer, whim, caprice, of modern motels & other road ephemera may have influenced Warhol’s later metallic silver factory decor. The seeds that might have been growing from Céline’s words: “Life is filigree work. What is written clearly is not worth much. It’s the transparency that counts.”“I don’t know what it was exactly, about the way we looked, Andy said a little disingenuously, when he recalled the incident a few year later. But he insisted that the ‘alien alert’ started flashing the moment they walked in, prompting curious locals to move closer for a better look.”

Gerard had just witnessed a mirage for the first time and penned a beautiful poem about it. Their heads were already in Hollywood meeting the in-crowd, the beautiful people, the famous who were to gather at Dennis Hopper’s party. Warhol was witnessing the art that was complete in itself, probably remembering the advice of his friend, “De,” who advised him not to leave his impressionistic brush stroke on the coke bottle. Paint it as it is. A new movement was forming. They met the master of change himself at the party: Duchamp, — and never looked back.

It is Ms. Davis’s style to pan to a faraway object, complete its history, then cinematically bring it into the focus of the story. John Huston becomes cinema verité. Her style permits one to learn everything related to the trip. Even things Andy Warhol’s diarist didn’t know. It is an education in detail. Here’s one: Howard Hughes was staying at a famous hotel where the Falcon four landed, courtesy of Hollywood elite, and had a standing order for a roast beef sandwich to be hung in a tree so he could stalk it at night. I thought I had read everything about Howard Hughes. Here’s another: The Falcon was designed to compete with the lean Volkswagen by none other than McNamara, later to be the liar with blood on his hands. Everything related to the story is explored, brought back into it. For instance, how the song “kicks on Rt. 66” came about. Even gossip became history. They put on “the put on” for the been there done thats. What’s inside is out, what’s outside is in.It’s also free from political correctness in that short window of time from the ’60s to the beginning of the ’70s (according to Mel Brooks), when the occupants of the Falcon could see Presley in “Viva Las Vegas” or Dean Martin, who “held the diminutive [Sammy] Davis in his arms and said that he’d like to ‘thank the NAACP for giving me this trophy.’” We learn that when they visited Palm Springs the rather square Bobby Kennedy was to get JFK in trouble again, this time with Frank Sinatra when he put his brother in the clean Republican crooner Bing Crosby’s place to make sure he wasn’t seen “playing house.” The copious details make me so nostalgic I wish they were back, and they will provide Gen X the essentials for a formative aesthetic needed at this time for how and why movements take shape.

The book is profusely documented like no other in modern publications I know, with pages full of notes, a bibliography, a precise index, and illustration credits. One can learn more about the aesthetic of THE movement of the age and its art from this book than from all the museum tracts and critical treatments, more about its neuromorphic seeds, its painting, its poetry (of the MacLiesh dictum “doesn’t have to mean but be”) than from all the modern art history books. Symbol becomes icon, icon becomes symbol. It’s a legacy now seen by the young who snap pics of the product, the brand, and say, “Oh Wow” to the symbols of their own roots morphed in the resonance of 1963, the movement in making.

The Trip: Andy Warhol’s Plastic Fantastic Cross-Country Adventure ends with a beautiful cinematic scene that almost brought tears to this aging hipster. Amid the obituaries and what happened to whom is Deborah Davis’s beautiful panoramic view of the once thriving billboard, neon lighted little town of Glenrio, Texas, now mostly abandoned, not worth tearing down, doors of buildings blown open for the tumbleweed secrets of the hipster’s “Benzedrine Highway,” once the great road from Chicago to L.A. called “America’s Main Street.” Now for mostly European tourists the fragments of the road leading nowhere. “Yet the thriving interstate is usually nearby,” she writes, “a parallel universe that is close, but worlds away.” I love this book. The Trip is a trip.

![Gerard Malanga (right) with Andy Warhol [1963]](http://www.artsjournal.com/herman/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Gerard-Malanga-right-with-Andy-Warhol-1963220.jpg)